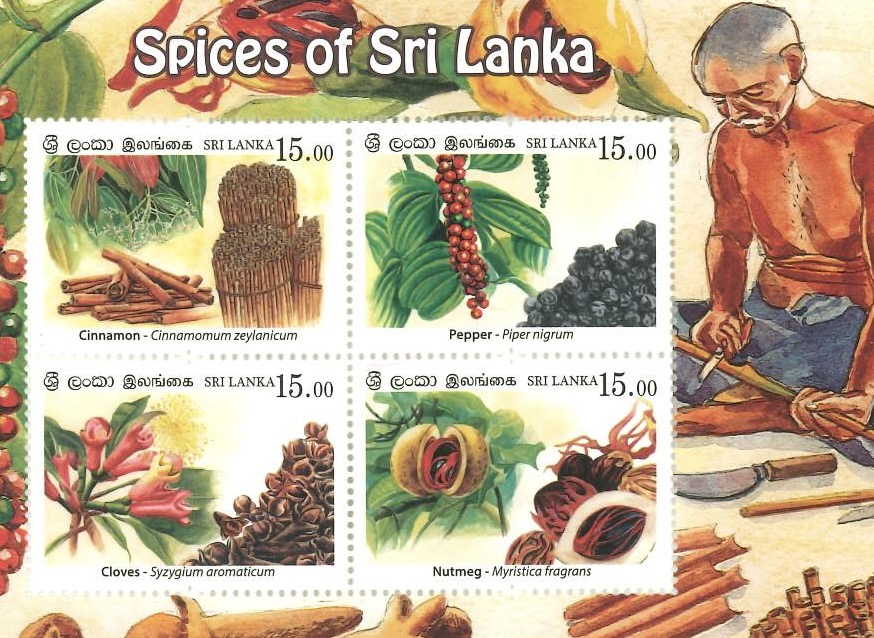

Before tea became the main industry of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), it was that attraction of spices that drove the Portuguese and Dutch to occupy the island. In 1505, a Portuguese fleet led by Lourenço de Almeida paid a visit to Colombo, they realized the richness of spices – cinnamon, black pepper, clove, nutmeg, etc. that were grown in the different parts of the island. Already established itself in several ports in India, the Portuguese immediately seized the opportunity to occupy Colombo and export this highly prized trade good directly to Europe. In the 16th and 17th centuries, black pepper was equivalent to commodity money and hence received the name “black gold”. The Portuguese began to build forts in order to secure control along coastal areas and monopoly in the spice trade. Ceylon’s role as a hub connecting trade in India and the Strait of Malacca was also firmly established.

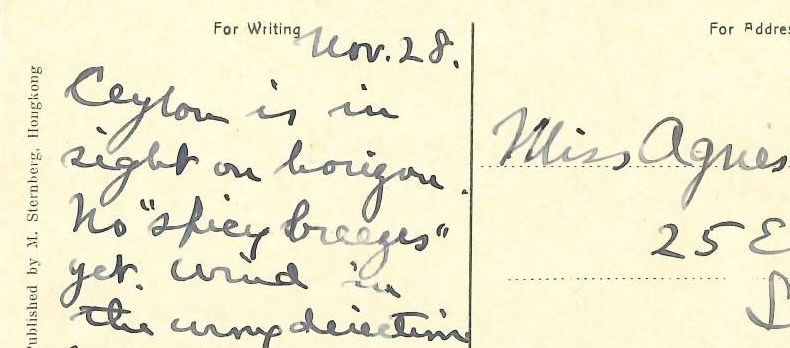

The writer of the postcard above was heading to Ceylon but had not had a chance to smell the “spicy breezes” that the island was famous for. The connection between Ceylon and “spicy breezes” came from the hymn “From Greenland’s Icy Mountains” composed by Bishop Reginald Heber (1783-1826) in 1819. One of the stanzas of the hymn mentioned Ceylon and described it as follows.1

What though the spicy breezes

Blow soft o’er Ceylon’s isle;

Though every prospect pleases,

And only man is vile?

In vain with lavish kindness

The gifts of God are strown;

The heathen in his blindness

Bows down to wood and stone.

The spicy scent came from the spices, especially Cinnamon – a popular spice used as a condiment to add aroma to a variety of dishes, foods, and drinks. There are different species of cinnamon and the species that is indigenous to Ceylon is called Cinnamomum verum. Before the 15th century, the overland spice trade from Asia to Europe was controlled by the Arabs and Italian traders from Venice and Genova. The Age of Discovery sparked global maritime trade and European domination in Asia. Ceylon was one of the countries undergoing admixture of culture and language during nearly four centuries of European expansion – the Portuguese period (1505–1658), followed by Dutch control (1658–1796), and finally British occupation (1796–1948). The presence of Europeans made the already multilingual and multicultural island even more diverse.

The circumstance produced a situation where a language was needed for communication. The language produced is known then as Ceylon Portuguese or today as Sri Lankan Creole Portuguese – a creole containing elements from Portuguese and the main local languages, particularly Sinhala and Tamil. Though the language began to be used in the Portuguese period, its importance and vitality continued into British Ceylon. This can be seen from John Callaway, a Wesleyan missionary, who wrote in the preface of his book: 2

“With thousands of inhabitants, this language is the direct medium of intercouse [sic]; and the fact of its having for centuries more than maintained its ground, under circumstances which have been fatal to other tongues, in addition to what has been remarked, is no contemptible evidence of its intrinsic worth.”

The grammar of the creole shows characteristics from the Portuguese and the local languages, as well as innovations. In Portuguese, tense is indicated through verb inflection. Verbs in Sri Lanka Creole, on the other hand, are usually unmarked. Instead, separate markers are used before verbs to indicate tense. The markers, all derived from Portuguese, are ta (< estar ‘to be’)for present, ja (já ‘already’) for past, and lo (logo ‘soon’) for future. The example below shows the use of the future marker lo.3

Muytu tambom lo-teem. very good FUT-be '[It] will be vrey good.'

Besides the admixture of language, a new ethnic group – the Eurasians – appeared as a result of intermarriage. As Portuguese soldiers, sailors, officials, traders, etc. who resided in Ceylon were mostly single men, marrying local women became a common practice. The children of such mixed-race marriages were called the Burghers. The Creole was not only spoken by adults as a lingua franca, but it was also the native language of the Burghers.

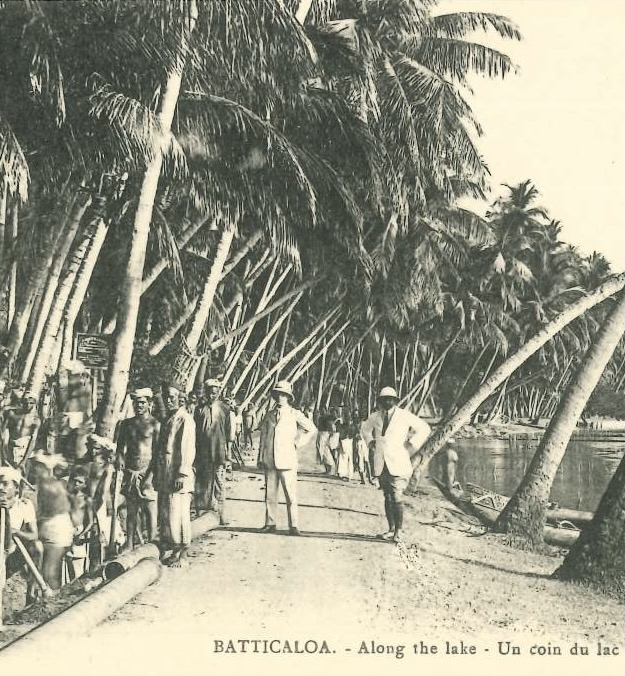

According to the 2012 population census, the number of Burgher was 38,293.4 The fact that Burgher is listed as a separate ethnicity indicates its historical and cultural significance in the country. After expelling the Portuguese in 1658, the Dutch took control of the island and the spice trade. However, since the creole was already a well-established lingua franca by that time, the Dutch burghers also spoke the language. Today Burghers mainly speak Sinhala, some additionally speak Tamil and English. Currently, Portuguese and Dutch Burghers mainly reside in the Batticaloa and Trincomalee Districts. The Sri Lanka Portuguese Burgher Foundation located in Batticaloa and the Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon in Colombo aim at preserving the core values and cultures of the Burgher community.

Let us enjoy the “spicy breezes” of Ceylon once again in this poem.5

Palms with the ocean dancing at their feet,

Groves where all the spicy breezes meet.

From lowland and highland, hill, river and vale,

Every zephyr recounts its fairy tale

Of a Buried City, a Tank or a Town

And many a treasure of great renown.

Taprobane, Lanka or Ceylon, ’tis the same,

A rose is as sweet by another name.

Palms with the ocean dancing at their feet,

Groves where all the spicy breezes meet.

We love their legends and the songs they sing,

Their comfort and sustenance to man and king.

We’ve sought one growing straight toward the skies,

For he who shall find it never dies,

Or a crooked areca or pure white crow,

If you happen to see one, let us know.

1. Hymnary.org. “From Greenland’s Icy Mountains”

2. Callaway, John. 1820. A Vocabulary, in the Ceylon Portuguese, and English Language. Colombo: Wesleyan Mission Press.

3. Ian R. Smith. 2013. Sri Lanka Portuguese. In: Michaelis, Susanne Maria & Maurer, Philippe & Haspelmath, Martin & Huber, Magnus (eds.) The survey of pidgin and creole languages. In “The survey of pidgin and creole languages”. Volume 2: Portuguese-based, Spanish-based, and French-based Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Online version available at: https://apics-online.info/surveys/41

4. Department of Census and Statistics – Sri Lanka

5. Maisondeau, N. 1909. Summer in Ceylon. Colombo: The “Ceylon Observer” Press.