Situated in southern China, the Pearl River (Zhujiang 珠江) is the third longest river in China. Life and customs along the river were so enchanting that they became a constable object of depiction in China trade art. A popular scene was boats of various sizes and functions – cargo boats, fast boats, Hoppo boats, flower boats, etc. traversing and floating on the river. These boats were also sites of intercultural exchanges.

River of Smoke (2011) is the second part of the Amitav Ghosh’s historical fiction Ibis trilogy; the other two parts are Sea of Poppies (2008) and Flood of Fire (2015). The main storyline of River of Smoke is set in 19th century Canton (Guangzhou), China. The main protagonist Seth Bahramji Naurozji Modi is a Parsi from Bombay. While establishing himself as an opium trader in Canton, Bahram, known to others as Barry Moddie, develops a relationship with a boat-woman Chi-mei (also called Li Shiu-je). Below is a dialogue between Bahram and Chi-mei in reconstructed Chinese Pidgin English. The language, consisting primarily of words drawn from English, as well as some words of Portuguese, Hindi, Malay, and Chinese origins, serves as the lingua franca to solve the language barriers between the Chinese and Westerners.

“Unlike some of the other washerwomen Chi-mei never asked for cumshaws or bakshish. She bargained vigorously for her dues but was content to leave it at that. Bahram tried to overpay her once, pushing a few extra pieces of copper into her hands. She counted it carefully then came running after him. ‘Mister Barry! Give too muchi cash. Here, this piece catchi.’

He tried to give it back but this only made her angry. She pointed to the gaudy flower-boats that were moored nearby. ‘That piece boat sing-song girlie have got. Mister Barry can catchi.’

‘Mister Barry no wanchi sing-song girlie.’

She shrugged, dropped the coins in his palm and walked away.

He was a little shamefaced when he saw her next and this seemed to amuse her. After the washing had been over, she whispered: ‘Mister Barry? Catchi, no-catchi, sing-song girl?

‘No catchi,’ he said. And then gathering his courage together, he said: ‘Mister Barry no wanchi sing-song girl. Wanchi Li Shiu-je.’

‘Wai-ah!’ she laughed. ‘Mister Barry talkee bad-thing la! Li Shiu-je no blongi sing-song girl ah.’ 1

Ghosh’s trilogy has been highly praised for its extensive research on the global trade network during the periods covered in the books. The books also contain a myriad of speech that reflect the modes of cross-cultural communication. While it is difficult to faithfully represent an extinct language like Chinese Pidgin English as shown in the extract above, the dialogue demonstrates some characteristic features of the pidgin. They include:

(a) The negation marker no occurs before verbs (no wanchi, no catchi).

(b) The word blongi (from English belong)is used as a copular ‘be’, as in Li Shiu-je no blongi sing-song girl ah, though in English language sources, it is more commonly spelt as belong, b’long, or blong.

(c) In the phrase that piece boat, piece serves as a classifier or measure word and the phrasal structure resembles that of the noun phrases in Cantonese.

(d) Have got could mean ‘to have’ and ‘to exist’ in the pidgin, and in the extract it means ‘exist’ (i.e. there is).

(e) Sentences in the pidgin basically follow the word order: subject – verb – object. However, the sentence this piece catchi shows a structure called topic – comment, where the topic here is this piece and the comment is catchi, with the subject you missing. The topic-comment structure is especially common in Cantonese. The process of moving a certain element in a sentence to the beginning of the sentence is called topicalization. The preposed element is usually the object of the sentence, as in this piece (copper coin) but need not be.

Nevertheless, as a recreation it is understandable that unusual features are also included. Masa (< Master) instead of Mister is a common term of address for foreigners. The vocabulary of the pidgin is in some way influenced by Cantonese. One example is expressing ‘give’. In addition to the verb give, the verb pay could also be used in the sense of ‘give’ and in fact more frequently than give. The source of the ‘give’ sense of pay can be attributed to phonological similarity with the verb bei2 , which means ‘give’, in Cantonese. Another example is the use of side. The adverbs here and there, whichare not used in pidgin English, are expressed as this side and that side respectively. These expressions are similar to the Cantonese expression ni1 dou6 呢到 ‘here’ and go2 dou6 嗰到 ‘there’, where ni1 ‘this’ and go2 ‘that’ are demonstratives and dou6 ‘place’ when following a demonstrative or a noun indicates location. The pidgin uses proper (also spelt plopa) has a range of meaning such as ‘correct(ly), proper(ly)’ depending on the context. So, talkee bad-thing would be more likely expressed as no talkee proper. The most interesting feature in the dialogue is the use of particles, namely la and ah in the reconstructed pidgin. In Cantonese, these words are called sentence final particles whose main functions include indicating the attitudes and confidence of the speaker towards the proposition. As the name indicates, such particles are found singly or in combination at the end of a sentence. While Cantonese is especially rich in sentence final particles, they are virtually absent in pidgin English, at least not in written sources. Wai-ah appears to represent 喂呀 (waai3 aa3) in Cantonese. The Cantonese interjection 哎吔 (ai1 jaa3), which expresses astonishment, disgust, disappointment, etc. depending on the variation in the voice. In fact, sources of pidgin English support the use of ai1 jaa3, usually spelt as Aiyah instead of wai-ah.

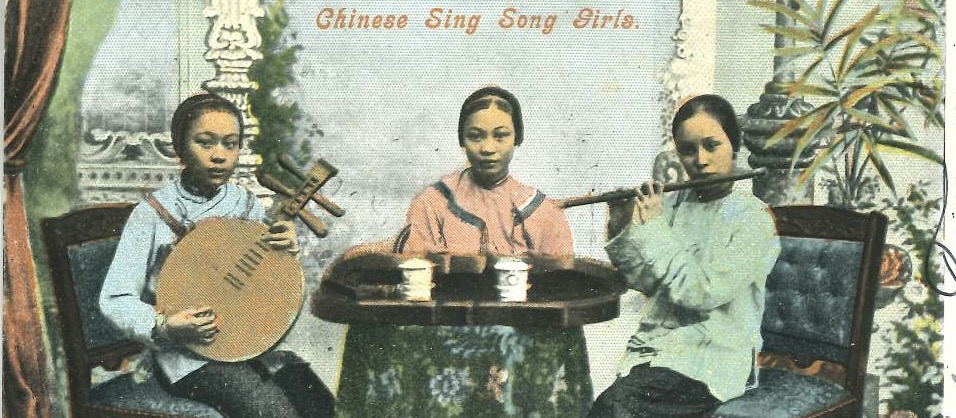

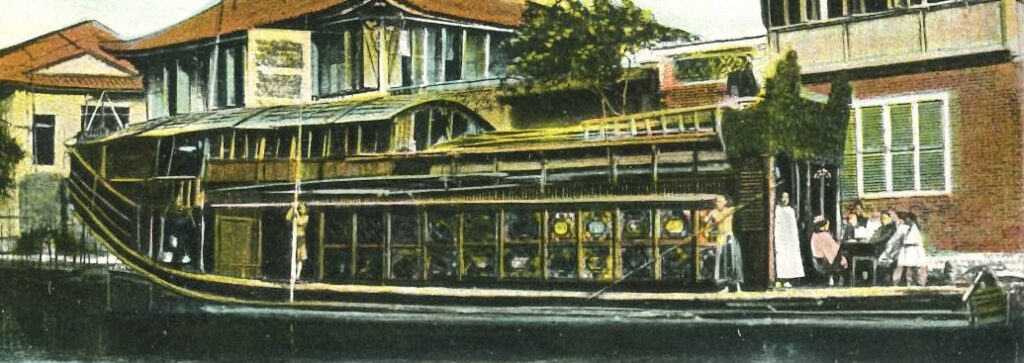

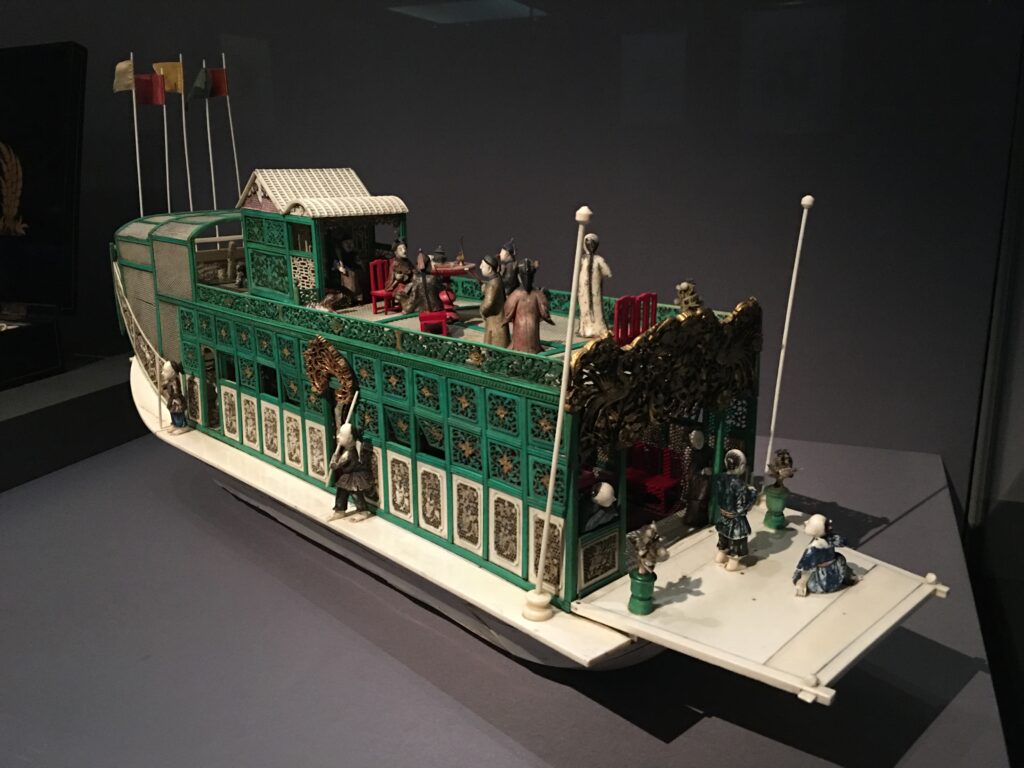

The word sing-song appears several times in the extract. Some foreigners used sing-song to describe the speech of the Chinese. Sing-song pidgin refers to theatricals and sing-song girlie is singing girl. That piece boat (flower boats) that Li Shiu-je mentioned are floating brothels. It was impossible for “Mister Barry” to catchi sing-song girlie on the flower boat as these boats were exclusively catered for the Chinese. Any foreigners breaching this rule would face severe punishment. Therefore, Sir William Tyrone Power, who served as Commissary General in Chief of the British Army and Agent-General for New Zealand, advised that it would be “very unsafe to attempt to visit one of the flower-boats in disguise, while openly it would be impossible to gain admission except by force.” 2

These superbly decorated boats had stained-glass windows, marble panels, black-wood framework, and black-wood furniture and in the interior there were a saloon in the centre and two or more small rooms at the bow and stern. The wealthy Chinese hired flower boats for feasting, drinking, opium-smoking, and other sensual pleasures.3 Sing-song girls would be present to play music and and sing songs to entertain the guests.

1. Ghosh, Amitav. 2011. River of Smoke. London: John Murray.

2. Power, W. Tyrone. 1853. Recollections of a Three Years’ Residence in China; Including Peregrinations in Spain, Morocco, Egypt, India, Australia, and New-Zealand. London: Richard Bentley.

3. Wilkinson, Ernest. 1888. “A glimpse at Chinese boat-life” By Ernest Wilkinson, Ensign, United States Navy. Frank Leslie’s Sunday Magazine. Vol. XXIV, no. 6. December.