The featured photography shows two Europeans and a group of South Asians. At the back of the photograph is: “Frank Arthur & servants. 3 years old!” So, this short phrase tells us the relationship between the European woman and the boy and the South Asians. Nowadays, it is unusual to have so many servants at home, but back in the days of British colonialism in India, this was quite normal in European homes.

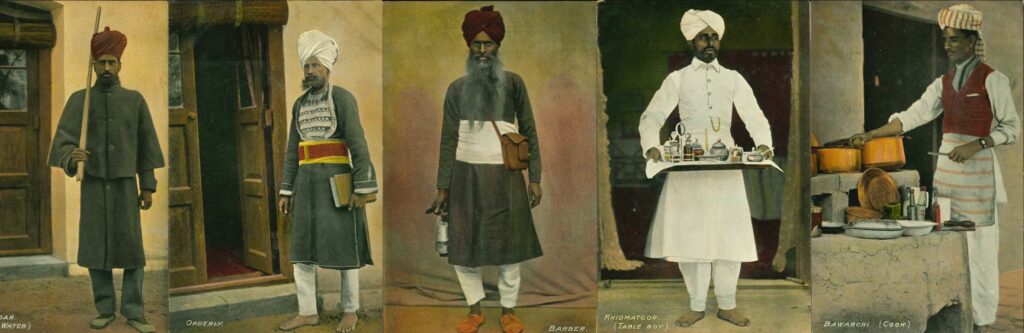

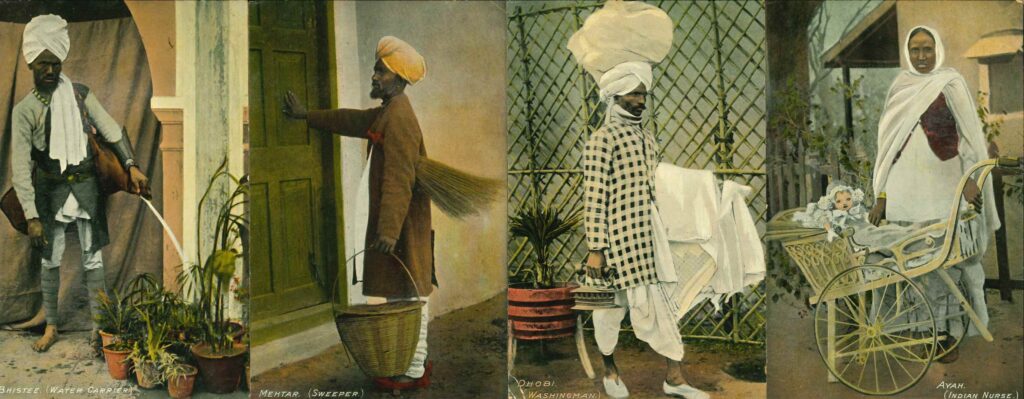

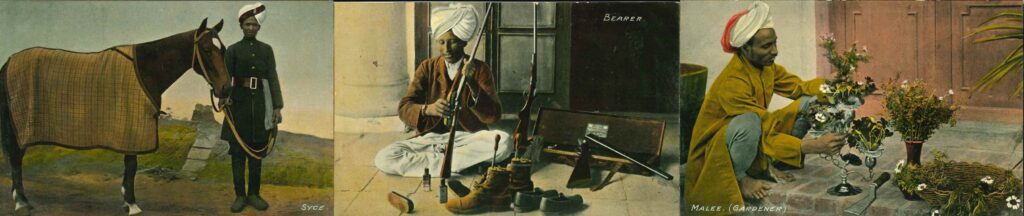

The connection between India and Britain dates back to the 17th century when the British East India Company (EIC) set foot in India. The East India Company was founded in 1600. Although it was a commercial company, it owned its private armies and exerted enormous influence over the society, economy, and politics of India. The Company gained permission to establish its first factory in Masulipatnam, located on the Eastern coast of India, in 1611. In the following decades, the Company continued to expand economic activities in India, and factories (commercial buildings) were built in different parts of the country such as Madras and Calcutta. The Company further consolidated control of India after her victory in the Battle of Plassey (1757) and the Battle of Buxar (1764), and by 1773 the EIC had direct governance of the country. Calcutta was designated the capital and Warren Hastings was appointed the first Governor-General. However, after the dissolution of the East India Company in 1874 and the India Rebellion of 1875, the British government took over the rule of India. British rule in India ended in 1947 when India became an independent country. Because of centuries of regular and prolonged interactions between the Indians and the British, the two cultures have developed intricate connections in various dimensions. Like the Portuguese traders, the early British settlers in India were mainly unmarried. However, while the single Portuguese men would marry local women, British rarely practised interracial marriage. During the British colonial rule, the number of British, including government officials, the military, settlers, and traders, increased significantly Some of them also brought their families to the colony. During this time, a European man was addressed as sahib ‘Sir, Master’, while a European woman was memsahib, formed by combining English ma’am and sahib.While the sahibs worked in offices, the memsahibs ran the household. The European wives would do household chores because doing menial work would be considered a loss of status. So the European homes employed native labourers. It was not unusual to see a dozen domestics working in European families since the number of domestic servants was also a symbol of wealth and status.1 Images of the servants also became the objects of depiction in postcards, like the series of postcards below. An ayah was a nursemaid whose duty was to look after the children. The Chinese equivalent was an amah. A syce took care of the horses.

The 19th century saw the height of the colonial expansion of the British Empire. After India, the East India Company extended its economic influence to Southeast Asia. The East India Company controlled the Straits Settlements, consisting of Penang, Malacca, and Singapore between 1826 and 1867, but in 1867 the Strait Settlements were under direct British rule. Singapore in the 19th century was as multicultural as today, and the main ethnic groups were Malay, Tamil, and Chinese. Consequently, European households might employ servants of different ethnicities. Jonas D. Vaughan’s career began as a shipman in the East India Company and later became a public officer and a lawyer. According to him, the ethnic groups in Singapore exhibit some general characteristics: “Chinese are excellent domestic servants. They are sober, industrious, methodical, and attentive to their duties…Many residents give the preference to the natives of Madras or Klings as they are called in the Straits. These invariably drink and are filthy in the extreme. The writer found a Kling cook once beating up a custard pudding with the stump of an old broom.”2

Hong Kong was a British colony between 1842 and 1997. As in India and the Straits, domestic servants were indispensable helpers in European houses. Ordinance No. 7 of 1866 gives the historical context in which the term “servant” was defined.3

“The term “Servant” shall mean every Chinese regularly employed in or about the dwelling house, office or business premises of any company, corporation, or person not being Chinese, in any of the following capacities:—

House boy, cook, cook’s mate, amah, coolie, watchman, gardener, coachman, horse boy, and boatman.”

Alfred Weatherhead worked in the Hong Kong Treasury and Supreme Court between 1856 and 1859. In his manuscript entitled Life in Hong Kong: 1856-1859, he gives an imagery dialogue between a European mistress and a Chinese cook through Chinese Pidgin English. The cook asks for the mistress’s permission to excuse him from work so that he can get married in Canton.4

Cook: Pakefuss lady sil (Breakfast ready Sir)

Missisee –my to morrow can go Cantonside two, three, day.

Mistress: What thing A-keen? What for you wantchee go?

Cook: My go catchee one piecey wife – belong takee care my house – look-see chilo – makey jacket.

In Hong Kong, European women were addressed as missy or missisee then. The cook and the mistress spoke Chinese Pidgin English, a lingua franca for people not sharing a native language. The language originated in Canton (now Guangzhou), but the British occupation of Hong Kong in 1842 attracted many Europeans to establish businesses in the colony. As a result, Chinese Pidgin English became a common medium for cross-cultural communication in the early days of the colony. Drawing inputs from Cantonese and English, the language has its linguistic characteristics. The spelling of the words shows the language’s phonetic features are different from English, for example adding extra syllables like -ee or -ey, -o, and -um after some consonants. It is common to add side after place names to indicate locations as in Cantonside. What for is used to ask for a reason instead of using why. Chinese Pidgin English is not meant to be used in all contexts, therefore, its lexicon is limited. Very often, a single word is used for multiple senses like catchee, whose meanings include ‘get’, ‘bring’, ‘catch’, ‘take’, etc. according to the context. But who will prepare the chow-chow (meals) during the cook’s absence?

Mistress: Suppose my talkee you can go, who man makee cook my chow-chow?

Cook: Maskee – belong my young blother can do – can boilum cay-chun, can roastum fowls – can makee No. 1 pudding, allo cook pigeon can fixee – no cazion feelo.

The cook reassures the mistress by saying maskee meaning ‘never mind, don’t worry’. The cook has a brother who can make different dishes like cay-chun 雞gaai1春ceon1 (i.e., chicken eggs), fowls, and very delicious pudding, so the mistress should not fear.

Besides using a lingua franca like Chinese Pidgin English, some Europeans would attempt to learn the local languages. Maye Wood wrote a phrasebook called Malay for Mems to allow the newly arrived European wives to learn the most basic and essential vocabulary and expressions in Malay. In Shanghai, Gilbert McIntosh compiled Useful Phrases in the Shanghai Dialect (1908) help residents and visitors to learn everyday words and phrases in the local dialect. Chapters were devoted to teaching readers to hold conversations with Chinese cook, houseboy and coolie, amah, tailor, washerman, and mafoo (i.e., groom).6

1. Chaudhuri, Nupur. 1994. Memsahibs and their servants in nineteenth-century India. Women’s History Review 3(4): 549-562.

2. Vaughan, J.D. 1879. The Manners and Customs of the Chinese of the Straits Settlements. Singapore: Mission Press.

3. Leach, A.J. 1890. The Ordinances of the Legislative Council of the Colony of Hongkong Commencing with the Year 1844. Vol. II. Hongkong: Noronha & Co., Government Printers.

4. Weatherhead, Alfred. n.d. Life in Hong Kong: 1856-1859. Manuscript.

5. Wood, Maye. 1949. Malay for Mems. Fifth edition.Singapore: Kelly & Walsh.

6. McIntosh, Gilbert. 1908. Useful Phrases in the Shanghai Dialect (second edition). Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press