The third day of the Chinese New Year is also known as 赤口 (Cantonese: cek3 hou2). Traditionally, it is believed that quarrelling will easily occur on this day, so it is not suitable for 拜年 (Cantonese: baai3 nin4) ‘pay New Year visits to relatives and friends’. Some people would go to temples to chin-chin joss ‘worship god’ to pray for prosperity in the new year, which is an important custom for Chinese people like the one shown below.1

“What do you do when you go to see Joss?”

“What thing my do? Chin-chin he, pay he kumshaw (present), pay that priestee man litty cash; he makee pray all the same my, by-and-by my go catchee chow chow long one piecee flend.”

The Wong Tai Sin Tample (黃大仙祠) and Che Kung Temple (車公廟) are two popular temples in Hong Kong.

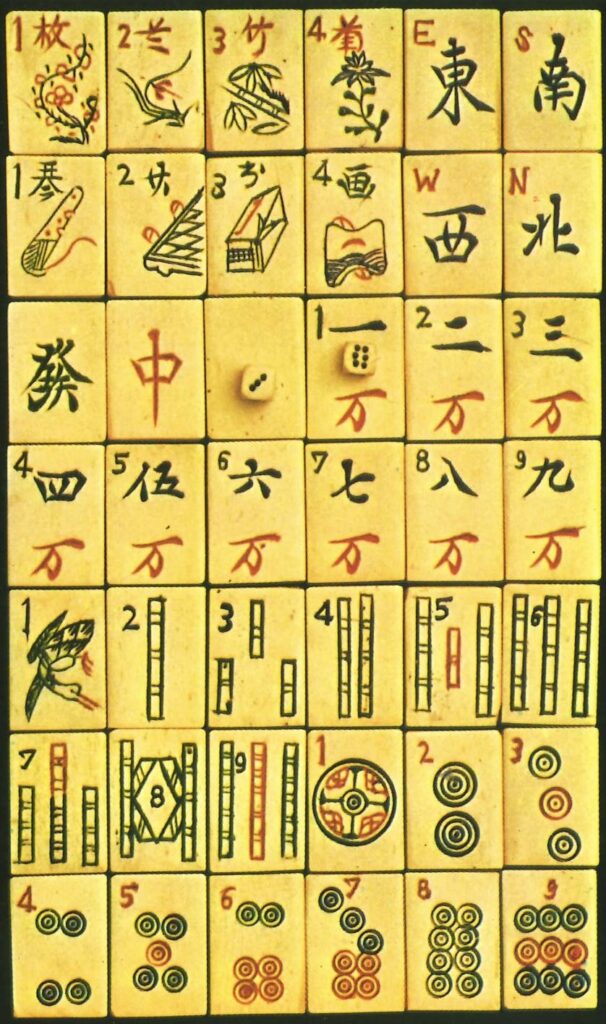

Other people would stay home and play games such as mahjong which is a tile-based, four players game. The game is not only widely played in China but also in East Asian, Southeast Asia, America, and Europe. Therefore, there are variations of the game in terms of the tiles used and rules.

In Hong Kong mahjong, a total of 144 tiles divided into different sets are used.

Three different suits designated as Dots, Bamboo, and Characters numbered one to nine make up a total of 108 tiles.

筒子 Dots (4 of each number 1 through 9)

索子 Bamboo (4 of each number 1 through 9)

萬子 Characters (4 of each number 1 through 9).

The Honors tiles, as they are called in the West, consist of Winds and Dragons and total 28 tiles.

Winds: 東 East, 南 South, 西 West, 北 North (4 of each)

Dragons: 中 Red, 發 Green, 白 White (4 of each)

There are eight flower tiles carved with drawings depicting the four plants collectively known as 四君子 ‘the four gentlemen’ and the four seasons.

Four Flowers: 梅 Plum blossom, 蘭 Orchid, 菊 Chrysanthemum, 竹 Bamboo (1 of each)

Four Seasons: 春 Spring, 夏 Summer, 秋 Autumn, 冬 Winter (1 of each)

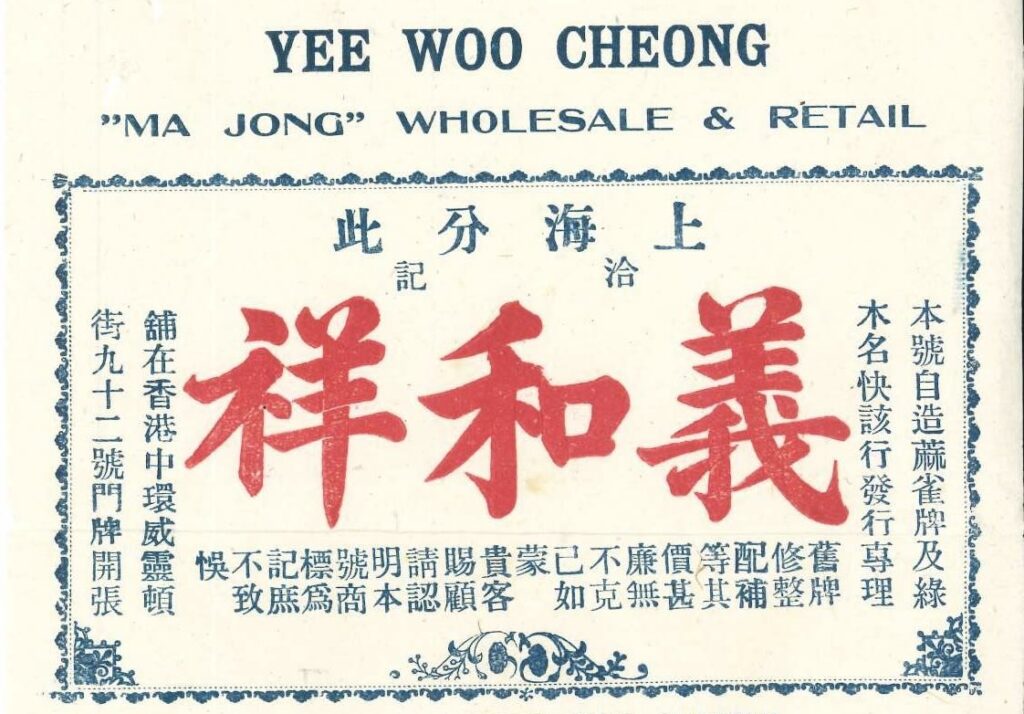

In Chinese, the game is mainly known as 麻雀 (Cantonese: maa4 zoek2) literally ‘sparrow’ or 麻將 (Cantonese: maa4 zoeng3). When the game was introduced to the Western countries, besides the common spelling mahjong, other names were also used including Ma-Cheuk, Mah-Cheung, Mah-Juck. While these spellings were transcriptions of the Chinese names, the name Pung Chow was sometimes seen too, for example in L. L. Harr’s instruction manual How to Pung Chow (1923: 16).2 Pung means 碰 ‘collide’ (Cantonese: pung3; Mandarin: pèng). A “pung” means a player has a set of three of a kind, for example three number 3 of character. To “pung”, a player can appropriate a tile discarded by another player to form a set of three of a kind and announces “pung”. Chow is a pidgin English word with an uncertain origin. In the pidgin English dialogue shown at the beginning of this article, the word chow chow is a noun meaning ‘food’ or ‘a mix of things’. Another usage of chow, as a verb,indicates the action ‘to eat’. In mahjong, “chow” refers to 吃(牌) ‘eat (tile)’. A “chow” means a player has three tiles of the same suit in a sequence, for example numbers 2, 3 and 4 of bamboo. If a player already has numbers 3 and 4 of Dot, he or she may “chow” the tile if the preceding player discards either 2 or 5 of Dot. Thus, forming a sequence of numbers 2, 3, 4 or numbers 3, 4, 5 of dot and announces “chow”.

In the 1920s, mahjong swept every part of America mainly due to Joseph P. Babcock, who worked in Suzhou, just outside Shanghai, and learnt the game from the Chinese. He promoted the tile game to Americans, trademarked the spelling “Mah-Jongg”, and introduced the simplified rules in his book Rules for Mah-Jongg (1920).3 Mah-jong quickly became a fashionable pastime for many Americans, especially women who might even dressed up in Chinese costumes while playing the game.

In China, however, Annelise Heinz found that the groups of Chinese intermediaries and elites comprising “officials, middlemen, compradors, industrialists, merchants, racketeers, and partisans knit Shanghai together and bridged the divide between foreigners and Chinese, though only rarely in social settings. Although Chinese residents made up the majority of the population, speaking Chinese was largely unnecessary for foreigner, whose only regular interpersonal interaction with Chinese people were servants who often had basic or pidgin English skills. Chinese elites and those educated in the West began introducing mahjong to foreigners by having numerals carved on the Chinese-numbered tiles, an innovation for which mahjong exporter Joseph Babcock would later take credit.” 4

In Southeast Asia, where a large number of Chinese, especially the Cantonese- and Hokkien-speaking immigrants, settled in the late 19th and 20th century, mahjong was undoubtedly one of the popular games. The jargon of mahjong also enters Singlish – the colloquial English spoken in Singapore. In Singlish anyhow has similar meaning as English anyhow. The word has two other related forms: anyhow whack and anyhow pong, where whack and pong are used as generic action words. The action that whack or pong indicates depends on the context. The Singaporean writer Gwee Li Sui explains in his book Spiaking Singlish that “[a]s for “pong”, it comes specially from the mahjong game, where a player forms a pong by grabbing three identical tiles and shouts “Pong!” People who anyhow pong in real life as in mahjong are dame one kind.” 5

For leisure, players can play mahjong noncompetitively while socializing with other players. Since players can easily spend hours on the game, there is usually a lot of chit-chat as in the mahjong scene depicted in Kee Thuan Chye’s play1984 – Here and Now below. The mahjong players are speaking in Malaysian English.6

player 3: Ay, doan tok so much la, Chuck your card. Wafor you tok so much? Wa can you do?

player 4: Cannot do anyting lah. Wat to do?

player 1: Every day, jus come gamble, pass der time, enough lah.

player 4: Ya, man. Wy boder? We can still do a bit of business, can have mistress, can jolly. Aiya, life is short la, wy worry so much, man?

player 2: You doan care aah if your son cannot get job in Gahmen office?

player 4: Cannot get, find oder job lah. Not say cannot get. You got brain, you got arm, you got leg, cannot die one la. Haisay, beautiful card la. Bes in der world!

In Malaysian English, the subject can be omitted if it can be inferred from the context. The “th” sound in English is represented as “t” or “d”, as in anyting, boder. A sequence of consonant sounds is often avoided, as in tok, jus, Gahmen. The sentence final particles like la and aah are commonly used in Chinese. The list of words may be helpful.

doan: don’t

tok: talk

wafor: what for ‘why’

wy: why

Gahmen: government

Aiya: an interjection

la, lah, aah: sentence final particles for expressing various emotions

In Hong Kong mahjong, one of the “bes in der world” combinations is 十三幺 (Cantonese: sap4 saam1 jiu1), translated as ‘thirteen unique wonders’. It is unique as it contains all kinds of tiles, that is, numbers 1 and 9 of each suits (Dot, Bamboo, Character), one of each Wind (East, South, West, North), one of each Dragon (Red, Green, White), and one of the above mentioned tile.

1. Anonymous. 1860. The Englishman in China. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co.

2. Harr, L. L. 1923. How to Pung-Chow: The Game of a Hundred Intelligences. Revised and enlarged edition. New York; London: Harper & Brothers.

3. Babcock, Joseph. 1920. Rules for Mah-Jongg. First edition.

4. Heinz, Annelise. 2021. Mahjong: A Chinese Game and the Making of Modern American Culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

5. Gwee, Li Sui. 2017. Spiaking Singlish: A Companion to How Singaporeans Communicate. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions.

6. Kee, Thuan Chye. 2001. “1984 – Here and Now”. In Helen Gilbert (ed.). Postcolonial Plays: An Anthology, pp. 250-272. London: Routledge.