Although the Ming dynasty of China (1368–1644) shut the door on establishing foreign relations in the 16th century, informal exchanges, particularly private trade, between the Portuguese and Chinese were common. Before being granted Macau as their settlement, Portuguese traders had to use outlying islands off coastal South China as their trading bases. One such base was Sancian Island (上川島), where the Jesuit missionary St. Francis Xavier stayed briefly and died there in 1552. Archeological finds of remnants of porcelains prove that the island was a prominent trading post at the time.

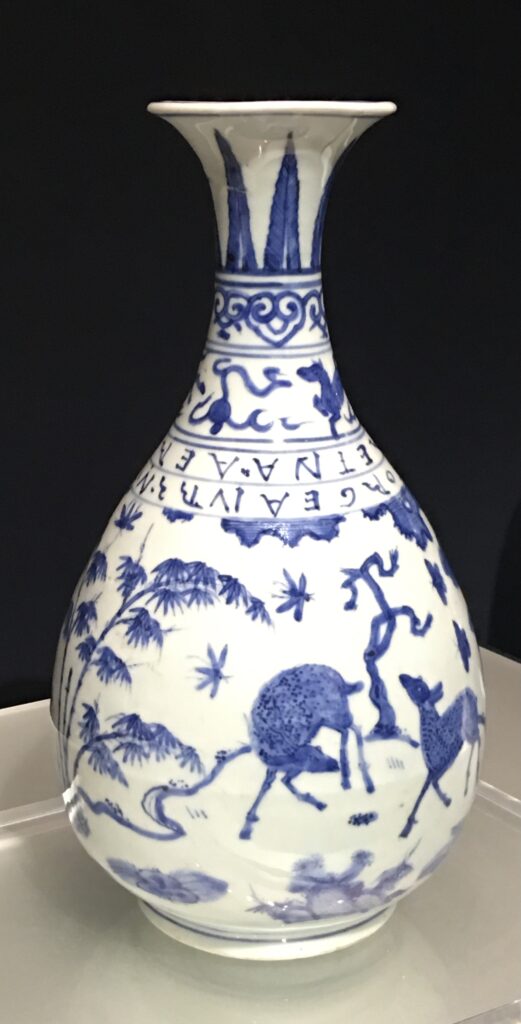

An example of highly lucrative trade was exported porcelain such as the blue and white porcelain shown in the photo at the right. Exported porcelains were often decorated with coats of arms of European families and companies and they even became collectibles of the high class. Since these porcelains were made for European customers, the designs differed from those used for the Chinese market. Another special feature of the vase was the Portuguese inscription, though written upside down, read like this: ISTO MANDOU FAZER JORGE ALVRZ NA ERA DE 1552 REINA “It is ordered for Jorge Alvrz in the year 1552 of the reign [of King John III].” The batch of vases was commissioned by Jorge Alvares (not to be confused with Jorge Álvares, the Portuguese explorer, who reached China in 1513 and died in 1521) in the Jiajing (嘉靖) period of the Ming dynasty.1 In 1557, China finally permitted the Portuguese to reside in Macau for an annual payment of 500 taels. This was the beginning of Macau becoming a Portuguese stronghold in the Far East and a hub for spreading Catholicism to East and Southeast Asian regions.

Photo (left): Yubuchun vase with deers and cranes design in underglaze blue; Eternal Enlightenment: The Virtual World of Jiajing Emperor exhibited at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, 2022.

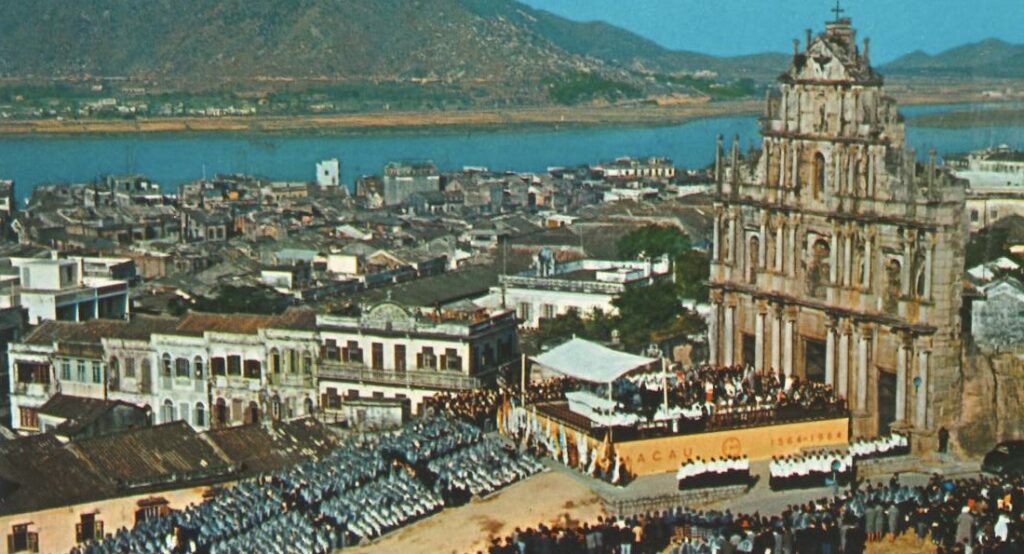

For 450 years, East-West encounters created different forms of plurality in Macau. First and foremost, the place has been referred to by many names in Chinese and Western languages – 濠鏡澳, 馬交,澳門 (hou4 geng3 ou3, maa5 gaau1, ou3 mun2 respectively in Cantonese pronunciation), and Amacao, to name a few. A name that is not very popular but preeminent is “Cidade do Nome de Deus de Macau” (City of the Name of God), granted during the period of the Iberian Union (1580–1640). The title pointed out that a major function of Macau was to serve as the centre of the Catholic faith in East and Southeast Asia. Visitors to Macau would be amazed by the number of churches on this small territory – the Ruins of St Paul’s, St Lawrence’s, St Anthony’s, St Dominic’s, St Augustine’s, the Cathedral, St Joseph’s Church, Chapel of Our Lady of Penha, Chapel of St Francis Xavier, etc. In addition, local and overseas Catholics are attracted by the large and small religious processions held throughout the year. When the Portuguese crown became independent from the Iberian Union, King Dom João IV added “Nao Ha Outra Mais Leal” (There Is None More Loyal) to Macau’s existing title to show appreciation for the loyalty of the people of Macau.

Plurality seems to be an inextricable and acknowledged feature of Macau since the beginning of East-West encounters in the 16th century. It is common to see the spellings “Macau” (e.g. University of Macau) and “Macao” (e.g. Macao Special Administrative Region) being used interchangeably as both spellings are officially accepted. Another area of plurality is the people of Macau. First, Portuguese were added to the existing local Chinese residents. Connections with Portuguese India and Malacca also brought Indians and Malays to Macau. Macau-Japan relations in trade and religion further diversified the population makeup. Finally, a new group of people – the Macanese 土生 (tou2 sang1) (also spelt Macaense in Portuguese sources), who are Eurasians of mixed Portuguese-Asian descent born in Macau, entered the picture. Early Portuguese settlers were mostly unmarried and they usually took Asian women such as the Malays, Indians, Japanese, and Chinese (especially the Tanka) as wives, concubines, or slaves and the children of such intermarriages identified themselves as the Macanese. As the meeting place of East and West, descriptions of Macau appeared in many historical accounts. Peter Muddy, a 17th-century trader, who travelled through Europe and Asia gave a vivid account of the people and customs in Macau. He observed that:2

“This place affoards very Many ritche Men, Cladde after the Portugall Manner. Their Weomen like to those att Goa in Sherazzees or [? and] lunghees, one over their head and the other aboutt their Middle Downe to their Feete, on which they were low Chappines. This is the Ordinary habitt of the weomen of Macao.”

Sherazzees comes from shīrā and means Persian shawls for mantillas; and lunghees means petticoats. Chappines refers to chopine. According to Mundy’s observation, there was a connection between Gao and Macau in women’s outfits. The picture on the left shows several Macaense women walking along the praia and dressed in what is known as dol in the Macanese language or 澳門土生土語 (Cantonese: ou3 mun2 tou2 sang1 tou2 jyu5) in Chinese. The word dol is etymologically related to the Portuguese word dó, meaning ‘pity’. This mourning attire was still popular among older women in the early 20th century but is hardly seen today. José dos Santos Ferreira (1919–1993, nicknamed Adé, was a writer who wrote poems, short stories, and plays in Macanese. He explains that dol is:3

“Espécie de touca de tecido preto, com que as velhas se cobrem, para irem à igreja. Nôs véla-véla têm-qui cubrí dol pa vai greza: nós, as velhas, temos de pôr o dol na cabeça para irmos à igreja. Dol provém de «dó», luto.

So dol is a black cloth that old Macanese ladies wear over their heads when going to church.

Macanese is a creole language and the native language of the mixed-race children in Macau. Like its birthplace Macau, the language has been called by several names including Patuá, Masquista, Papiaçám di Macau, etc. An example sentence in Macanese is seen in Ferreira’s definition of dol.

Macanese: Nôs véla-véla têm-qui cubrí dol pa vai greza.

Portuguese: Nós, as velhas, temos de pôr o dol na cabeça para irmos à igreja.

English: ‘We, the old women, have to put the dol on our heads to go to church.’

Even though the lexicon of Macanese is largely based on Portuguese, there are many differences between the two languages such that they are not mutually intelligible. Let’s see how dissimilar they are. The forms of personal pronouns in Portuguese vary depending on several criteria: number (singular or plural), gender (masculine or feminine in the third person, and case (subject, object, possessive), for example, nós ‘we’ (subject), nos ‘us’ (object), and nosso(s)/nossa(s). Macanese does have distinct forms of singular (iou ‘I/me’) and plural (nôs ‘we/us’) personal pronouns, but identical forms are used for gender and case. In Portuguese, verb conjugation reflects the grammatical properties (person, number) of the subject and the tense of the sentence. Therefore, the forms temos and irmos indicate present tense and first person plural subject pronoun (nós ‘we’). Tense is not shown as verb inflection in Macanese so the forms of têm, cubrí, and vai remain unchanged regardless of the tense and the grammatical properties of the subject. Number distinction in nouns is shown as inflection in Portuguese too, for example, a velha ‘the old woman’ and as velhas ‘the old women’, and the definite article a(s) ‘the’ must agree with the noun it modifies in number and gender in Portuguese. Macanese employs, on the other hand, a completely different representation, namely reduplication, i.e. copying the same form as in véla-véla ‘old women’ to indicate plural. Macanese has comparatively fewer prepositions than Portuguese. In cases where a preposition is needed in Portuguese, it is often left out in Macanese, for example, à ‘to’ in the above example. Moreover, prepositions such as pa express multiple meanings and functions in Macanese. Though many Macanese words originate from Portuguese, they are spelt differently from their source language. This indicates that the phonetics and phonology of the two languages are also different.3, 4

Centuries of intercultural contact have made Macanese a dynamic language responding to various social changes in Macau. In the 16th and 17th centuries, linguistic influence from Malay and Indian langugages via Indo-Portuguese and Malacca Creole (also known as Kristang) play a significant role. As the the number of Chinese increased between the 18th and 19th centuries, Chinese influence, particularly Cantonese, became more evident. The handover of sovereignty to China in 1999 made Putonghua more and more important in Macau. Though Macanese is facing an uncertain future due to a severe decrease in the number of speakers in the last century, it does not change the fact that it is Macanese, both as a people and a language, that makes Macau unique.

1. Jin, Guoping 金國平and Wu Zhiliang 吳志良. 2006. Ming and Qing dynasty Chinese Porcelain in Portugal 流散于葡萄牙的中國明清瓷器. Palace Museum Journal 故宮博物院院刊 3: 98-112.

2. Temple, Sir Richard Carnac. 1919. The Travels of Peter Muddy, in Europe and Asia, 1608-1667, vol. III. Travels in England, India, China, Etc. 1634-1638, part I. Travels in England, Western India, Achin, Macao, and the Canton River, 1634-1637. London: Hakluyt Society.

3. Ferreira, José dos Santos. 1996. Papiaçám di Macau. Macau: Fundação Macau.

4. Fernandes, Miguel Senna and Alan Norman Baxter. 2004. Maquista Chapado. Vocabulary and Expressions in Macao’s Portuguese Creole. Macao: Cultural Institute of the Macao Special Administrative Region.