After the landing of the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in Calicut (now Kozhikode), India in 1498 and upon his return to Lisbon with news of future profits of the spice trade in the subcontinent, Portugal quickly organized more expeditions to conquer India before its rival Spain. In order to secure a permanent presence in the Indian Ocean, the first viceroy of Portuguese India was appointed in 1505 and Goa was captured in 1510. In subsequent years, factories, trading posts, and forts were established in major port cities like Diu and Daman.

The British East India Company (EIC), founded in 1600, was eager to have a share in the East Indies trade. Though the initial interest of the English traders in India was primarily commercial, the EIC grew into a giant enterprise and its sphere of influence eventually extended into economic and political domination over the Indians in the 18th century. Following the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857, the British Crown took over the territorial possessions of the EIC and began direct rule in India. The term British India or Britsh Raj refers to the period of direct British rule from 1858 to 1947. EIC was nationalized and finally dissolved in 1874. Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India in 1877.

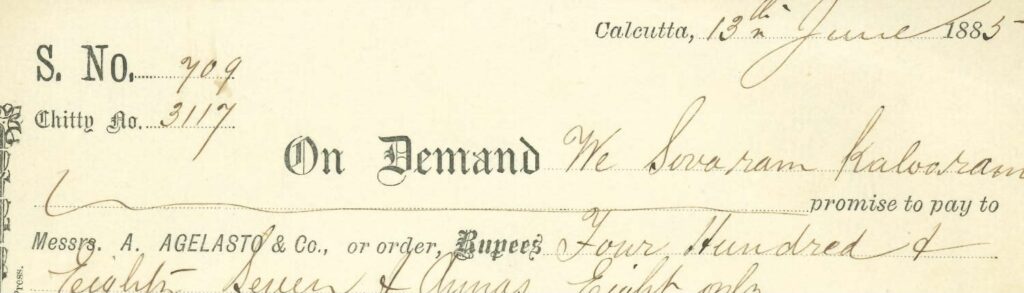

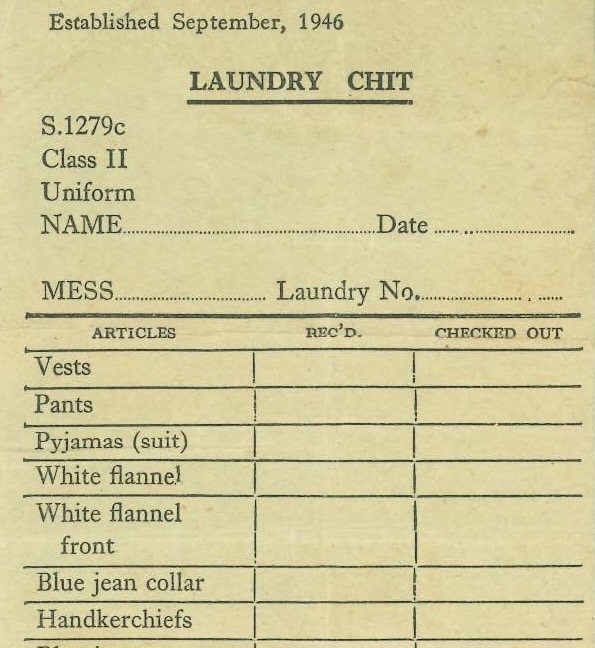

The featured image above is a promissory note issued by A. Agelasto & Co. of Calcutta in 1885. Two sets of numbers are shown: S. No. typically stands for serial number and a number called Chitty No. Chitty is an obsolete word originating from India.Constant interactions between the British and Indian cultures resulted in a considerable number of Indian words being borrowed into the lexicon of English. One example of the Anglo-Indian vocabulary is chitty and the short form chit. According to the Hobson-Jobson Glossary, chitty and chit refer to “[a] letter or note; also a certificate given to a servant, or the like.” The anglicized forms are derived from Hindi chiṭṭhī or Marathi chittī. It is of note that the glossary also mentions that the Indian Portuguese use chito for the Portuguese word escrito ‘written.’1 The word appears in an article on the revenues of Bombay in The Indian Antiquary of 1925 along with an explanation of its possible origins.2

“Chito. The meaning of this item is obscure. The Portuguese word chito is the same as escrito= ‘anything written,’ ‘a note of hand.’ It might possibly be a Portuguese corruption of Marâṭhî chiṭṭha, meaning ‘pay-roll,’ ‘general account of revenue’ etc., or of Kanarese chiṭṭhi meaning ‘a roll of lands under cultivation.’ It may perhaps be assumed to signify miscellaneous revenue written up in the roll.”

Although British endeavour to trade in China in the 17th century ended with opposition and hostility from China, the opening of the port at Canton (present-day Guangzhou) for foreign trade in the 18th century, followed by the establishment of other treaty ports in the aftermath of the two Opium Wars, British investment in the China trade was full steam ahead.

Communication was an important challenge; as a result, a contact language emerged in the 18th century to serve as a bridge for interethnic communication. This language was then called by different names – Canton jargon, Canton English, Pigeon/Pidgin English and is now commonly known as Chinese Pidgin English. While essentially a pidgin language combining features from Chinese, specifically Cantonese, and English, there is also a few words of Indian origin, for example, chop ‘a seal, a stamp,’ shroff ‘cashier, money changer’ and coolie. The keyword of this article – chit – is another example. As sending chits was a customary mode of communication among foreign residents in 19th century China, the Chinese servants, like “postmen,” carried the chits from house to house or hong (a firm) to hong. The delivery men had to make sure that every chit was delivered successfully and recorded in his chit-book as described by a traveller to China below.3

“The term letter, or note, is unknown, and replaced by that of chit. On the chit you stamp the name of the hong to which it is going, in Chinese, with small wooden blocks provided for the purpose, just as our post-offices stamp in red. To insure the safe delivery of your “chit,” you keep a chit-book, in which you enter the date and the name of the person to whom you are writing; and woe betide that cooly who returns to you with the book unsigned by the recipient!”

Chinese Pidgin English was the day-to-day medium of communication between the Chinese and foreigners in the 19th century. For this reason, different pidgin phrasebooks were sold and one particularly valuable phrasebook is The Chinese and English Instructor published in 1862. The author of the book Tong Ting-kü (also Tong King-sing) was a Cantonese merchant and compradore (a middleman working for foreign firms). To facilitate Chinese readers to learn English words, characters are used to transcribe English. For example, the character 切 when pronounced in Cantonese cit3 can more or less represent the English pronunciation of chit. as in the following example.4

Pidgin: 忒 利士 切 哥 煲士 阿非士 (Tong 1862)

Gloss: take this chit go post office

English: ‘take this letter to post office’

Chits continued to be circulated well into the 20th century. Aleko Lilius, the American journalist who had the rare opportunity of sailing with the “Queen of Pirates” – Madam Lai Choi San, recalled his encounter with a Chinese man in his book I Sailed with Chinese Pirates.5

Chinese: Solly. You fliends of Si Nai Lai?

Si Nai (師奶 si1 naai1) is a colloquial term of address for Mrs in Cantonese; the more formal equivalent is 太太 taai3 taai2. Lai refers to the female pirate Lai Choi San. Lilius replied with an affirmation and the Chinese told him the whereabouts of Lai.

Chinese: She Canton. She my cousin. I take you shoreside – you take boat Canton. I give you chit. You see her Canton.3

The Chinese man’s English, which was commented on by Lilius as “fairly good,” somehow resembles characteristics of Chinese Pidgin English. For example, the ubiquitous use of the “l” sound in place of “r” as the latter sound does not exist in Cantonese (solly); the absence of the copular verb be (She my cousin); the absence of prepositions before locations (you take boat Canton), which is the same as the example in Tong’s book.

The use of chit to refer to a note acknowledging a sum owed to someone, like the promissory note at the top of the page, continued to exist in the late 20th century. A foreign expatriate who was employed in a trading company in Hong Kong in the 1980s described how the chit system worked.6

“We had a magic thing called the ‘compradore account’, and whenever you wanted some money you went down to the basement of the office, to a little cash counter, signed a chit, and somebody gave you the money. At the end of the month it was knocked off your salary.”

In fact, besides advancing money, chits were also used as proof of purchase without immediate payment. Though the word chit is no longer used, buying goods on credit or “buy now, pay later” continues to be a prevalent consumer practice.

1. Yule, Henry and Arthur Coke Burnell. 1886. Hobson-Jobson Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms. London: John Murray.

2. Edwardes, S. M. 1925. The revenues of Bombay. The Indian Antiquary. Volume LIV. January 1925.

3. Anonymous. 1860. The Englishman in China. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co.

4. Tong Ting-kü 唐廷樞. 1862. The Chinese and English Instructor 英語集全. Canton.

5. Lilius, Aleko E. 1930. I Sailed with Chinese Pirates. London: Arrowsmith.

6. Holdsworth, May and Caroline Courtauld. 2002. Foreign Devils: Expatriates in Hong Kong. Oxford: Oxford University Press.