In the 18th century, Europeans and their employees worked in a “Factory”, not to produce goods but to engage in different commercial activities. The featured image above is an advertisement for a shop located at “Old Factory Street”. The advertisement appeared in a travel guide A Pictorial Handbook to Canton published in 1905. By this time, there was no more “Factory” in Canton. The sense of “Factory” as used in the street name is different from its current use in English. The origin of “Factory” dates back to the Age of Discovery between the 15th and the 17th centuries, when the Portuguese and other Europeans started exploring the world. The historical use of “Factory” is related to the Portuguese word feitoria, which means ‘trading post’, or a commercial building established for trading.The expansion of the Portuguese empire in the 15th and 16th centuries brought the word to places like Africa and the Indian subcontinent, where they established their feitorias. The Portuguese word eventually became the form “Factory” in English.Whether feitoria or factory, the word not only has a long history, it also travelled half of the world and appeared in China.

All foreign trades were confined to Canton before 1842, and there was a strict separation of the Chinese and foreign communities. The “foreign devils”, as foreigners were called then, had to live and work in the Factories. The area where these commercial establishments were located was known as the ‘Thirteen Factories” (十sap6三saam1行hong2), sometimes called Hong (from Cantonese 行hong2). William C. Hunter, an old China hand and long-time Canton resident, gives a finer distinction between the two terms in his memoir.1 “The words Factory and Hong were interchangeable, although not identical. The former, as will have been seen, consisted of dwellings and offices combined. The latter not only contained numerous offices for employés, cooks, messengers, weighmasters, &c, but were of vast extent, and capable of receiving an entire ship’s cargo, as well as quantities of teas and silk. When speaking of their own residences, foreigners generally used the word ‘Factories;’ when of a Hong merchant’s place of business, the word Hong.”

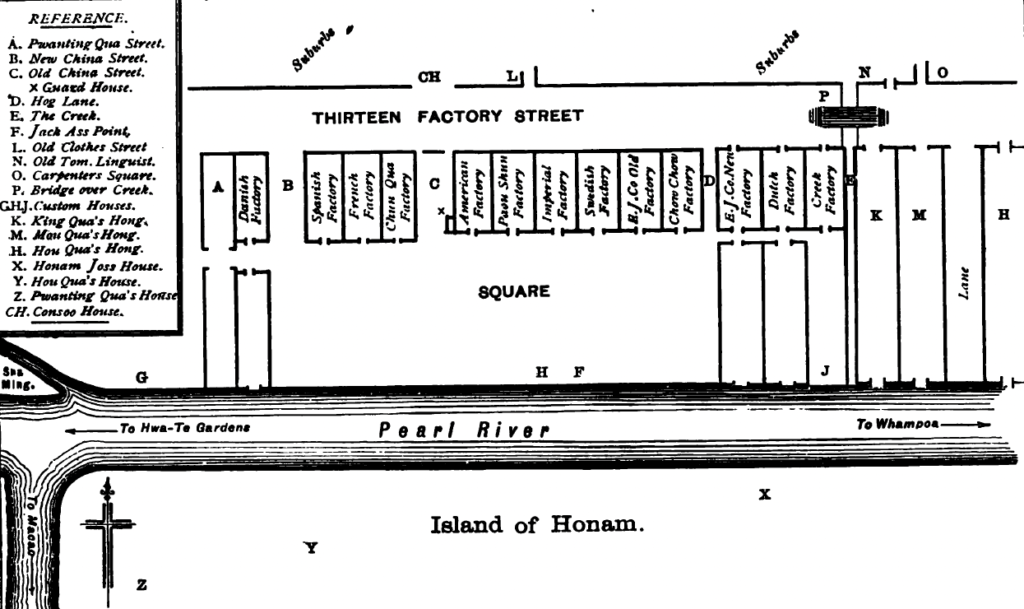

As we can see from the map in Hunter’s book, the frontage of the Factories faced the Pearl River. Aarranged from west to east were: Danish Factory (黃wong4旗kei4行hong2), Spanish Factory (大daai6呂leoi5宋sung3行hong2), French Factory (高gou1公gung1行hong2), Chunqua’s Factory (中zung1和wo4行hong2), American Factory (廣gwong2源jyun4行hong2), Paou Shun Factory (寶bou2順seon6行hong2), Imperial Factory (孖maa1鷹jing1行hong2), Swedish Factory (瑞seoi6行hong2), E.I.C. Old Factory (隆lung4順seon6行hong2) [E.I.C.: English East India Company], Chow-chow Factory (豐fung1泰taai3行hong2), E.I.C. New Factory (保bou2和wo4行hong2), Dutch Factory (集zaap6義ji6行hong2), and Creek Factory (怡ji4和wo2行hong2). The Chinese name of the Spanish Factory actually refers to 呂leoi5宋sung3, that is Luzon, the largest island in the Philippines. In China, 呂leoi5宋sung3 could also refer to the Philippines. Since the Philippines was still ruled by Spain in the 19th century, Spain was referred to as 大daai6呂leoi5宋sung3 ‘greater Luzon’, while Luzon/Philippines was 小siu2呂leoi5宋sung3 ‘smaller Luzon’. Chowchow is a pidgin English word, meaning ‘food, eat, mixed’. The Chowchow Factory was so named because the residents were of different nationalities. The three streets that ran parallel to the Factories were New Chinese Street, Old China Street, and Hog Lane. At the rear of the Factories, running from west to east, was a long street called Thirteen Factory Street. On these streets were shops selling different products like curios, herbs, tobacco, porcelain, silks, shoes, clothes, and many more. As foreigners were confined to the Factory quarter before the First Opium War (1839–1842), strolling through these streets, shopping, bargaining, and chitchatting with the Chinese shopkeepers were the main entertainments for them.

As a unique existence within Canton, the Factory quarter stood out from the rest of the surrounding environment because of the spatial fusion of different people, cultures, architecture, and businesses. Such visible cross-cultural blending may explain the popularity of the “Thirteen Factories” as a recurring motif in export paintings, porcelain, and fans. Inside the Factory, the workplace was also multicultural. Besides the taipans or heads of the Factory, there were different types of Chinese employees. The compradores who were secured by a Hong merchant and acted as middlemen were the key people. He oversaw matters related to the business and supervised other Chinese staff such as the shroffs and the clerks in the office. Since Europeans also dwelled in the Factory, the compradores also supervised domestic staff like the boys, cooks, coolies, and amahs.

Only a small group of licensed Chinese merchants called the Hong merchants were allowed to trade directly with the Europeans. This privilege gave these merchants a monopoly in import-export trade. The most influential and famous Hong merchant was 伍ng5秉bing2鑑gaam3 (1769–1843), or Houqua (also Howqua) as the Europeans called him. His Hong was called 怡和 (Ewo). Houqua was not only rich but also developed close partnership and relationship with many European traders including William Jardine and James Matheson – the taipans of Jardine, Matheson and Company. The fact that Jardine and Matheson took Houqua’s Hong name 怡和 as the Chinese name of their company showed their respect for him.

Communication between the European and Hong merchants would normally be conducted in Chinese Pidgin English. William C. Hunter gives an example of what a conversation between Houqua and a European would be like. The conversation is about the flood of the Yellow River, and the Mandarin demands Houqua to pay a large sum of money for the repair work. So, the conversation unfolds like this:

European: Well, Houqua, hav got news to-day?

Houqua: Hav got too muchee bad news, Hwang Ho hav spilum too muchee.

European: Man-ta-le hav come see you?

Houqua: He no come see my, he sendee come one piece “chop.” He come to-mollo. He wantchee my two-lac dollar.

European: You pay he how mutchee?

Houqua: My pay he fitty, sikky tousand so.

European: But s’pose he no contentee?

Houqua: S’pose he, No. 1, no contentee, my pay he one lac.

Now, let’s look at a few linguistic characteristics of Chinese Pidgin English, a medium employed by both Chinese and Europeans to enable communication. The pidgin language possesses features that resemble and differ from its main sources of input, namely Cantonese and English. Adding an extra vowel, such as “ee”, after some consonants is commonly seen in the pidgin, for example, muchee, sendee, and contentee. Other vowels are also used, as in “um” in spilum (spill) and “o” in to-mollo (tomorrow). A Man-ta-le is a mandarin (a government official). Conditional sentences are introduce by s’pose (suppose). Two words in the conversation are from India. Lac is derived from the unit lakh meaning 100,000 in the Indian numbering system. Chop is another word from India. It has multiple meanings ‘seal, stamp, document, licence’. In the conversation, it probably refers to an official notice from the mandarin. The exchange is a good example of a common practice in the China trade: “squeeze”, meaning excessive demand for money or bribery.

1. Hunter, William C. 1882. The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days 1825–1844. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co.