The modern world is not unfamiliar with different types of mixing – mix-and-match in fashion, crossover in music, fusion in food… you name it. However, mixing different languages seems to irk many people, as it is often seen as a sign of inadequacy. Whichever form of mixing is the case, it requires contact or clashes between people of different cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Pidgins and creoles are examples of language mixing par excellence. Pidgins and creoles are called contact languages because they emerged under the sociohistorical context of maritime exploration, economic exploitation, and colonialism of the 16th to 19th centuries. People often mistake pidgin and creole languages as a bunch of languages mixed together in an unstructured manner and consequently, pejorative descriptions such as “corrupted,” “broken,” and “baby talk” are used to label them.

Chinese Pidgin English is one of the best-known pidgins in the world. Originating in Canton (now Guangzhou), China in the 18th century, what might have been conjectured as a transient solution for the communication barrier at the time turned out to last for more than 200 years. In the Ming dynasty, China imposed the sea ban on private trade, which was essentially an isolationist policy that separated China from the rest of the world. The sea ban extended well into the early Qing dynasty. Things took a turn in 1757 when restricted trade was permitted in Canton, then the only port allowed for foreign traders to enter. Here came the problem: the scarcity of language experts was a serious hindrance to commercial exchanges. It was against this background that led to the emergence of Chinese Pidgin English. A popular etymology of the word pidgin is that it was the Chinese way of pronouncing the English word business. Following the close of the First Opium War in 1842, China was forced to more treaty ports, hence, marking the golden era of foreign trade, as well as Chinese Pidgin English. The language was not just used by the Chinese but by anyone who lacked a shared language to make themselves understood. English and Cantonese are the main languages contributing to the core of CPE. Though the overwhelming vocabulary comes from English, words of other origins such as Portuguese , Malay, Hindi, and Chinese are also found due to the extensive and interconnected trading networks. The grammar, as you will see in the example below, is a fusion of English and Cantonese.

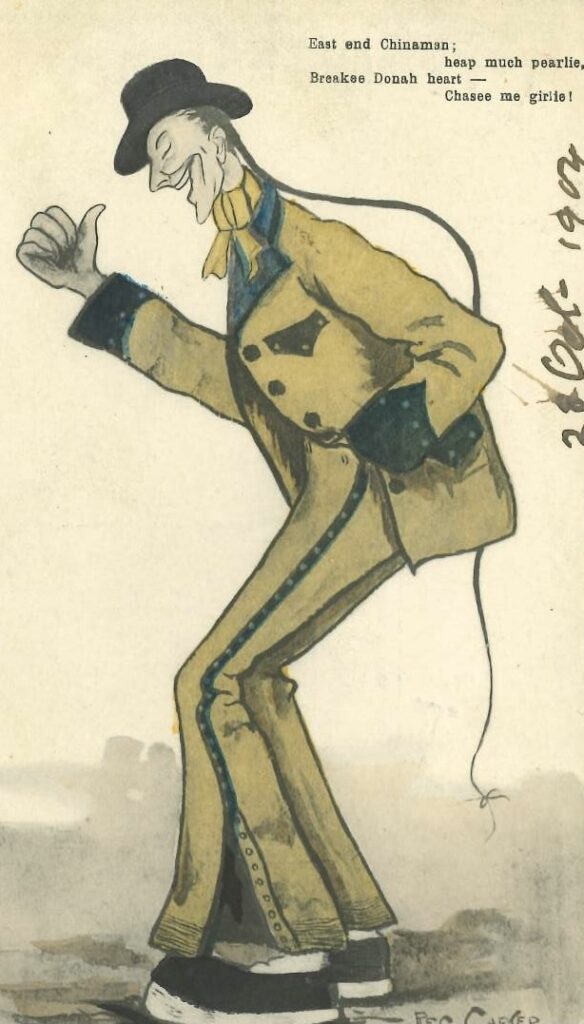

The opening of China not only attracted numerous foreign traders but also visitors and Chinese Pidgin English, as a medium of communication, became a topic of discussion in the West. Charles G. Leland, for example, used a form of pidgin English to write his book Pidgin-English Sing-Song. The book was so widely read that between 1876 and 1924 ten editions were published.1 Some writers like Julian Ralph mentioned below employed invented pidgin English to represent the voice of the Chinese characters in their stories. Unfortunately, many Western writers had little first-hand experience in using Chinese Pidgin English, and the pidgin they depicted was often mimicry. A Shanghai correspondent with the initials D. T. wrote to the periodical The Nation to criticize the unauthentic and biased representation of pidgin English. Since it was unusual for Westerners to give testimonials to pidgin English, it is worth quoting D. T.’s commentary in full and here you are.

CARELESS MAGAZINE WRITING.2

TO THE EDITOR OF THE NATION:

SIR: In Harper’s Magazine for November, which arrived here yesterday morning, I have just read Julian Ralph’s second story of Anglo-Chinese life, entitled “Plumblossom Beebe’s Adventures,” illustrated by C. D. Weldon. The tale touches the seamy side of life in a Treaty Port, and to the great uninitiated public of America it will probably seem a picturesque and accurate delineation of facts. Julian Ralph is a clever journalist, well practised in taking superficial notes of what he sees, and in holding his pitcher-ear wide open for the yarns he may hear, all with a view to working up literary material of his own. I give him full credit for what he has accomplished, but it is the merest hack-work at best. We have all been laughing at his “pidgin English” out here—we call it Ralphese, for it is nowhere spoken in China as his characters speak it.

Pidgin English is not in the least like “English baby prattle,” as Julian Ralph states on page 946 of the magazine. Of course, to a globe trotter it may sound so for a few days, but as soon as he tries to obtain a serious knowledge of it, he should not fail to see that it is a very valuable compromise between Chinese grammar and phonetics and those of European nations. It is not a haphazard, meaningless babble, invented to soothe small children; it has regular rules of construction, and is not left to the individual whim of a globe-trotter.

On the first page of his story Ralph exhausts his smattering of the lingo, and says in excuse, “The pidgin English is too confusing to follow farther.” Why did he begin? Let me give the Ralphese and the real pidgin English of page 942 of the magazine, in parallel columns:

RALPHESE

“He comes some other side, in countly,” said the go-between. “He belong kidnap girl—some man have tief her.* Been tlained singsong girl, but no can do: no gottee good voice. He velly good girl—can plomise† he alle time have been velly good.”

“But she is not alive,” said Sam. “No belong girl—belong wooden t’ing. What for she no move no laugh no belong alive girl? Have makee die? My wantschee one piece gal can makee play-pidgin, makee laugh makee chin-chin.”

*Nominative and objective cases are identical in Chinese, therefore in pidgin English. There is only one third-person pronoun, which in Chinese is “ta,” translated he in English, but in reality masculine or feminine according to context. †“Plomise” is not pidgin-English but Ralphese. The word is secure, pronounced “secuah.”

PIDGIN ENGLISH

“He have come other side countlee. He belong stealum girlee—some tief man catchee he. Have teachee he do sing song girlee pidgin, he no good, no can sing ploper. That girlee heart velly good—can secure he allo time have velly good.”

“He no belong ’live.” “No belong girlee—belong one piecee wood. What for he no makee move, no makee laugh, no belong ’live girlee? He have makee die? My wantchee one piecee girlee can makee play, makee laugh, can talkee-talkee.

It is high time that the up-to-date journalist abroad were taught not to dabble in what he knows nothing of. On page 946 there is nearly a column of utterly uncalled for vituperation of foreign residents in China as a class. They, however, entertained him hospitably when he was here, filled him with food and drink and his literary knapsack with provender, which he has shamefully wasted. It is not true that we “repeat the silliest and most cruel lies that can be found in books upon China,” such, for instance, as “that all Chinese eat dogs and rats, slaughter or sell their girl babies, beat their wives and often killed them, have no hearts, never show affection, never bathe or wash, and so on ad infinitum.” These statements, it is true, appear in most books about China, because most books about China are written by folk who have spent three or four months in the country.

James Payn’s ‘By Proxy’ is absurd, so far as accuracy is concerned, and so is Hannan’s ‘A Swallow’s Wing’; but both those stories of China, written many years ago, are excellent literature compared with Ralph’s realistic romances. Jules Verne’s ‘Tribulations of a Chinaman’ is also superior. D. T.

SHANGHAI, December 19, 1895

Let’s take a look at some of the “regular rules of construction” in Pidgin English.

- English sounds that do not exist in Cantonese are replaced, for example “l” instead of “r”.

- An additional vowel (-ee, -o, -um) is added to words ending in certain consonants.

- Belong is used as a copular verb instead of be.

- Use of piecee as a classifier before nouns.

- No inflectional markings on verbs and nouns; infinitival or bare forms are used instead.

- Omission of subject and/or object is acceptable as the context can help retrieve the referent(s).

- Makee is used before a verb to indicate action.

Though Chinese Pidgin English is not a fully-fledged language, the language is “a very valuable compromise” as D. T. rightly pointed out. Through international collaboration, the language enables communication instead of shutting each other off.

1. Leland, Charles G. 1876. Pidgin-English Sing-Song. First edition. London: Trübner & Co.

2. D. T. 1896. “Careless magazine writing” The Nation Jan 30, vol. 62, no. 1596, p. 98.