“Hong Kong prospère sous le signe de la cumshaw et le sourire des sing-song girls” (Hong Kong thrives under the sign of the cumshaw and the smile of the sing-song girls) was the topic of a 1948 issue of a French magazine. Hong Kong was under Japanese occupation for three years and eight months (December 1941 – August 1945). The post-WWII period was definitely monumental in the history of Hong Kong not only because of the swift revival of economic and social activities but also changes in social structure. The period saw important political and social transitions in China. In 1945, the population of Hong Kong was just about 600,000, but in 1951 the population surged to 2 million. The vast majority of people who made up the increase in population was immigrants from China comprising of businesspeople, entrepreneurs, skilled and unskilled labourers, farmers, etc. Political unrest in China resulted in the influx of people from different provinces of China to settle in Hong Kong. More importantly, what they brought with them included capital, assets, skills, knowledge, languages, cultures, customs, etc. The Chinese immigrants transformed the economic and social structures of post-war Hong Kong and gave rise to modern Hong Kong. Turning back to the title of the French article. You may wonder what cumshaw (also cumsha) had to do with the prosperity of Hong Kong. To answer this question, we have to understand what the word means.

Cumsha(w) originated in Chinese Pidgin English – a language emerged in the context of Canton trade to facilitate communication between Chinese and foreigners in the 18th century and was used well into the 20th century in Hong Kong. The meaning of cumsha(w) evolved over time and was often translated as ‘a present’, ‘charges on vessels’, ‘gratuity’, ‘alms’, ‘bride’, ‘payoff’, ‘commission’, and ‘a tip’. One proposal of its origin was that it was a corruption of the English phrase “come ashore” – call of the boat women of Canton to entice the Western sailors. However, the Chinese origin was more popular. John Robert Morrison (1814 – 1843), son of Robert Morrison (1782–1834) – the first protestant missionary to China, wrote in “Glossary of words and phrases to the jargon spoken at Canton” (1834) that:1

“cumsha probably from Fuhkeen kum-seäh, ‘I will thank you,’ — or from Canton kum sha, ‘a sand of gold,’—denotes a gift, a present. Certain charges on vessels, which were originally presents, are so called. This word, and the phrase ‘can do?’ are the first expression learned by the Chinese, and are in universal use in Canton.”

Morrison mentioned two Chinese sources – kum-seäh 感謝 literally meaning ‘grateful’ in Fuhkeen (i.e., Hokkien spoken in Fujian province) and kum sha 金沙 literally ‘gold sand’ in Cantonese. The Hokkien origin is widely acknowleged. The characters 金沙 , pronounced gam1 saa1 in Cantonese, could be the transcription of the Hokkien word or an actual form of present back then.

William C. Hunter (1812 – 1891), an American trade who had extensive knowledge on China trade, described how cumsha(w) was collected from foreign ships at the time of Canton trade.2

“Before she (any ship) could open hatches, the formality of “Cumsha and Measurement” had to be gone through. The first word signifies “present”, and was a payment made by the earliest foreign vessels for the privilege of entering the port.”

The New Year is the most one of the important festivals for the Chinese. It is customary for Chinese to send presents to people during this period. In old Canton, William C. Hunter recalled that the Hong merchants would send valuable cumshas or presents, including the finest teas, black lacquer inlaid with mother-of-pearl, embroideries and shawls, the finest grass cloth, dried fruits, etc.to the members of a Factory whom they had close business connections with. The foreign traders usually sent these items home as presents but some might sell them to get some extra money. Hunter (1885: 227) remarked that “The teas thus acquired and disposed of gave the name (familiarised afterward) in the American and English markets of Cumsha teas.”

In the International Exhibition (officially known as the London International Exhibition of Industry and Art) held from 1 May to 1 November 1862 in London, an exhibited item was Cumshaw Tea and a report on it in the Lancet described it as follows:3

“The box numbered 28 contains Cumshaw Tea, made up in the shape of balls, faggots, and cigars, intended only as presents, and but rarely sold, or even to be met with.”

Another account mentioned the value and rarity of this kind of present.4

“Mr. Gray gave me today a half pound canister of cumshaw tea, which is said to be worth 3000$ the picul, or about twenty-three and half dollars a pound. It was given to him by their tea merchant, as a rare present.”

Albert Rasmussen arrived in China in 1905 and stayed in the country for 32 years. Initially, he worked in the Customs in Chinkiang (Zhenjiang 鎮江), where a small British Concession was established. One of his hobbies was wild boar-shooting. On one occasion, he stayed in a bungalow kept by a Chinese called Chun, who told him in pidgin English stories about the good old days.5

“That time, Master, plenty man come shootee shootee pig.

Evely week four five piecee man come. My catchee plenty cumsha.”

Chun used to get a lot of cumsha (tips) because many visitors (plenty man) came to the place to hunt boars in the past. Chinese has different classifiers or measure words that combine with different types of nouns. For example, in Cantonese zek3 隻 is usually used with animals as in 一隻豬 jat1 zek3 zyu1 ‘one zek3 pig’. Go3 can be used with a wide range of nouns, such as humans 一個人 jat1 go3 jan4 ‘one go3 human’. In pidgin English, only one classifier existed: piecee. The pattern [numeral + piecee + noun] as in four five piecee man is similar to the Cantonese examples.

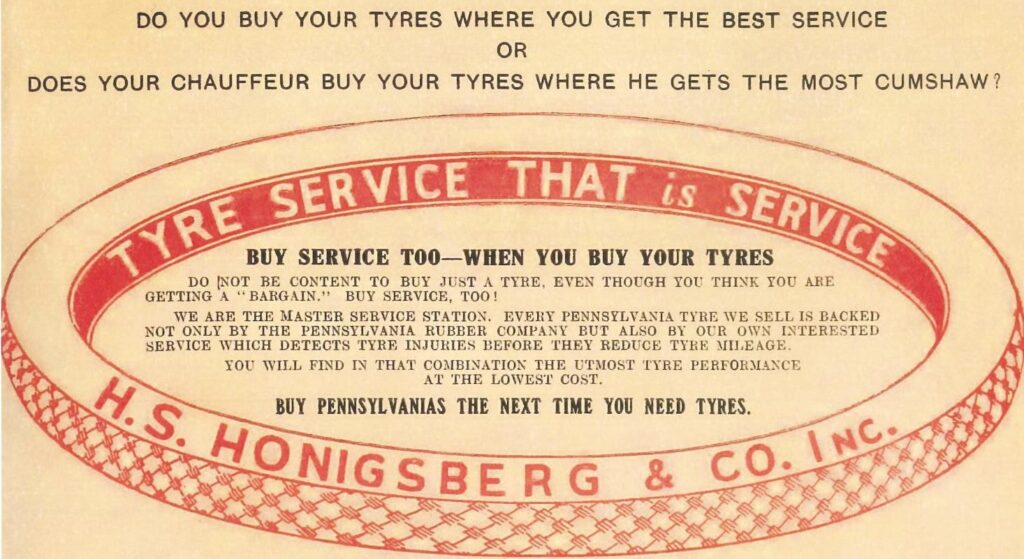

On the left-hand side is an advertisement of H.S. Honigsberg & Co., Inc., an American automobiles dealer located at Bubbling Well Road (now Nanjing West Road) in Shanghai. The word cumshaw as used in the advertisement “Does your chauffeur buy your tyres where he gets the most cumshaw?” could mean ‘commission’, ‘bride’ or ‘tip’, depending on the agreement between the chauffeur and the service provider.6

1. Morrison, John Robert. 1834. A Chinese Commercial Guide Consisting of a Collection of Details Respecting Foreign Trade in China. Canton China : Printed at the Albion Press.

2. Hunter, William C. 1885. Bits of Old China. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co.

3. The Lancet. No. XIX. Vol. II.November 8, 1862. P. 512. “The Great International Exhibition. XVIII. Report on the substances used for good exhibited in class III.”

4. Preble, George Henry. 1962. The Opening of Japan A Diary of Discovery in the Far East, 1853-1856. From the Original Manuscript in the Massachusetts Historical Society. Edited by Boleslaw Szczesniak. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

5. Rasmussen, Albert H. 1954. China Trader. London: Constable and Company Ltd.

6. The Oriental Motor, March 1921.