Titled “A coolie of Hongkong”, the featured postcard portrays a rather unusual representation of coolies – unhassled and calm. On the back of the postcard, there is a short message: “This is a common sight here – everything is carried by coolies they put the pole over their shoulders & a basket on each end. That’s how my coal & groceries & everything carries up the hill!” Apparently, coolies were employed for doing menial work such as carrying things or transporting people for very little money. As shown in the last post (16. Boy), coolies received the lowest wage compared with other domestic workers like the boy, amah, and cook. An early transliteration of the coolie (also cooly)in Cantonese is 咕gu1喱lei1, a term mainly used in Hong Kong. Another Chinese term for coolie is 苦fu2力lik6 not only approximates the phonetics of the coolie but also a translation of their characteristic through the choice of Chinese characters: 苦fu2 means ‘bitter, hard’ and 力lik6 means ‘labour, strength’. Coolie is an early Indian English word and its form may be related to various languages of India: Gujarati koḷī, Portuguese cule, Hindi kūlī, kulī, Bengali kuli, etc., and Tamil kūli.

In 19th-century Hong Kong, the term coolie was used to denote unskilled workers. In European families, apart from the boy, the cook, the amah, the coolies were also indispensable as they would take up the “coolie pidgin”, i.e., laborious tasks. An Englishman notices different types of coolies in China.1

“Turn we now to coolies, —I mean those attached to your house. If we go by names, we shall have plenty,—house-coolies, chair coolies, garden-coolies, Comprador’s coolies, office-coolies, lamp-coolies, bedroom-coolies, water-coolies, —in fact, ad libitum you may go on enumerating them. But when you sift the matter, it is different. If you inquire for the lamp-cooly, it is just likely a man will appear who, the next moment, will say “Here!” to the title of water-cooly, while, later in the day, he will be hard at work sweeping and raking, having transformed himself into an impromptu garden cooly. Therefore, although in each house at Shanghai we have, as in all Eastern countries, crowds of servants, yet it often occurs that a cooly receives a title which is only honorary, and caused by his present occupation.”

In a household where “crowds of servants” work together, it is inevitable to see arguments and hierarchy. The houseboy or “number one boy”, being a personal attendant to the European employer, exerted pride and privilege to designate what were “boy pidgin” and “coolie pidgin” as illustrated in the dialogue below where the employer asks the boy to do what belongs to the duty of the coolie, the boy replies:2

Boy: No can; that no my pigeon” (business). “My talkee that cooly man; he belong that pigeon.

Despite the employer’s insistence, the boy would not give up his dignity easily, so he protests:

Boy: No can, no can. I no sarvy that cooly man pigeon. I talkee he, — he come chop chop.

The boy is speaking a language called Chinese Pidgin English. This is a language created out of a need to have a language that can be used by people speaking native tongues, as in the situation described above. It draws on words and grammar from English and Cantonese (the primary language spoken in Canton and Hong Kong), but other languages also participate, for example, coolie is from India. Chinese Pidgin English was first spoken in Canton (now Guangzhou) and was later spread to Shanghai and Hong Kong. While employed initially in business communication, Chinese Pidgin English was also used in other cross-cultural interactions such as in the household. The word pidgin, or spelt pigeon in some sources,as in the name of the language is believed to be a pronunciation of business by the Chinese. So cooly pigeon refers to the duties of the coolies. No can is a versatile expression in the pidgin and denotes the negation of things relating to ability, possibility, or permission depending on the context. Chop-chop,still heard sporadically today, means ‘quick’. A peculiar feature of Chinese Pidgin English is using my as thesubject position, alongside I. In fact, my also appears in object position and as a possessive adjective like my pigeon. As for the third person pronouns, Chinese Pidgin English uses he only regardless of gender, number, and grammatical function.

Apart from working as servants in households, many Chinese also travelled abroad for work during the 19th century. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, about 12 million enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas to work in plantation fields. However, Britain ended the slave trade when the Slave Trade Abolition Act was passed in 1807. Other European nations and America followed.3 In order to find replacements for the immense vacuum of labour force, contract or indentured labourers were recruited from Asia, particularly from China and India. Numerous of Chinese labourers emigrated and worked as gold miners and construction workers in North America and Australia. The condition of Chinese labourers leaving for South America in the 19th century was the most perilous. While the Chinese in America signed their contracts at their own will, those Chinese working in Peru and Cuba were often abducted or kidnapped. The trade was referred to as the coolie trade (1846 – 1874), but note the Chinese immigrants were also called “asiaticos” and “colonos”.5 In Chinese, the trade is known as 賣maai6豬zyu1仔zai2(‘sale of piglets’): 賣maai6 means ‘sell’ and 豬zyu1仔zai2 literally means ‘piglet’ but here it refers to the Chinese labour. The main port of embarkation was Macau, where Chinese coolies were held in 豬zyu1仔zai2館gun2 (barracoon from Portuguese barracão) waiting to be shipped to Peru or Cuba.4

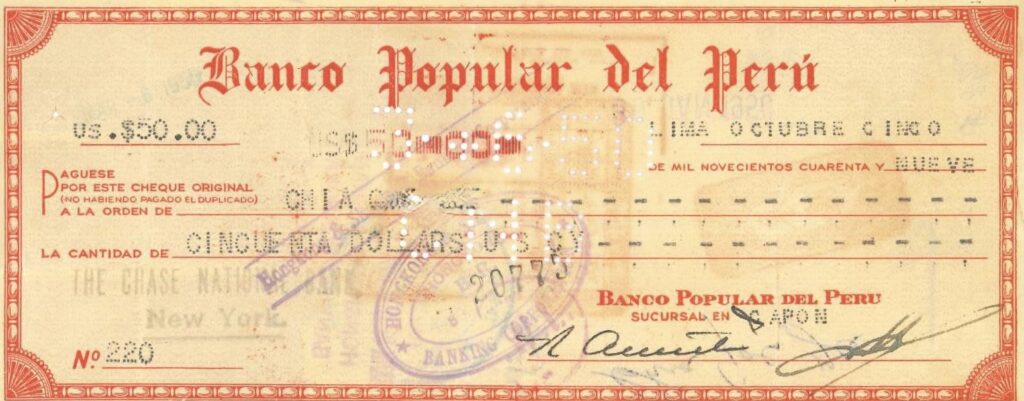

Many Chinese labourers stayed behind and adopted Spanish names after completing their contracts. As they were single males, marrying local women was common. Today the number of Peruvians and Cubans of Chinese ancestry is considerable. While the period of coolie trade has long gone, many Chinese still maintain some connections with their families in China. One type of evidence of such bondage is sending remittance back home, as seen in the bank check above.

1. Anonymous. 1860. Englishman in China. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co.

2. Ball, B.L. 1855 Rambles in Eastern Asia, Including China and Manilla. Boston: James French and Company.

3. Thomas, Hugh. 1997. The Slave Trade: The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440 – 1870. New York: Simon & Schuster.

4. Asome, John. 2020. Coolie Ships of the Chinese Diaspora 1846-1874. Proverse Hong Kong: Hong Kong.