As China opened up its market for foreign trade, the flow of people, money, ideas, and technologies from around the world expanded exponentially. The signing of the Treaty of Nanking (1842) after the First Opium War (1839-1842) meant enormous opportunities for investment in China. Trade was no longer restricted to Canton, new ports like Shanghai and Hong Kong were the new playgrounds of investors and travellers. Shanghai was no doubt the most international and sophisticated Chinese port city. After the war, the British, French, and Americans were among the first foreigners to establish companies and settle in Shanghai. The Shanghai International Settlement was established in 1863 after the merger between the British and American enclaves. Germans, Italians, Japanese, etc. followed.

The Treaty of Nanking (1842) not only granted trade privileges to the European powers but also rights of extraterritoriality and jurisdiction. Although still under Chinese sovereignty, the International Settlement in Shanghai was essentially a self-governed body under the management of the Shanghai Municipal Council 上海公共租界工部局, founded in 1854 and ceased to function in 1943. During this long period of self-governance, the council was dominated by the British. It was not until 1928 that Chinese members were allowed to join the council. The power of the council was multifaceted, including law enforcement, jurisdiction, postal services, transportation, power supply, taxation, and construction of roads as shown on the postcard on the right.

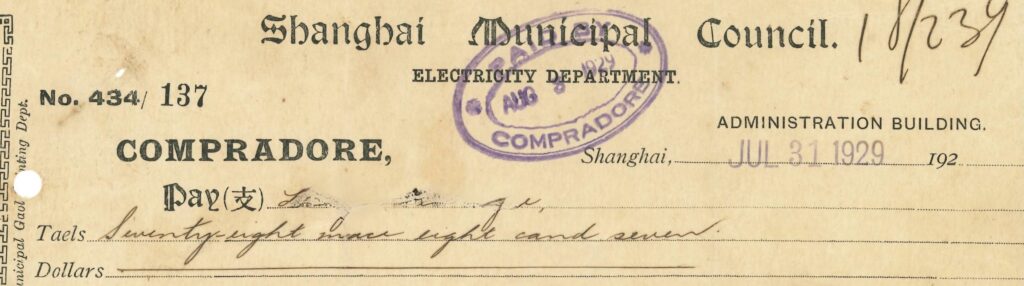

The featured receipt was a refund issued by the Electricity Department of the Shanghai Municipal Council. The word that stands out the most on the receipt is the word compradore. The word is of Portuguese origin: the verb comprar means ‘buy’ and a comprador is a buyer. The compradore was a position that arose from the Canton trade and the lifestyles of the compradores were a unique mix of Eastern and Western practices. The duties of compradores changed over time. In the Canton days, a compradore was a native Chinese who oversaw various matters related to his European employer. The American trader William C. Hunter gives a rather detailed description of the compradore’s duties.1

“The most important Chinese within the Factory* was Compradore. He was secured by a Hong merchant in all that related to good conduct generally, honesty and capability. All Chinese employed in any factory, whether as his own ‘pursers’ or in the capacity of servants, cooks, or coolies, were the Compradore’s ‘own people;’ they rendered to him every ‘allegiance,’ and he ‘secured’ them as regards good behaviour and honesty. This was another feature that contribute to the admirable order and safety which characterised life at Canton. The Compradore also exercised a general surveillance over everything that relate to the internal economy of the ‘house’ as well as over outside shopmen, mechanics, or tradespeople employed by it. With the aid of his assistants, the house and private accounts of the members were kept. He was the purveyor for the table, and generally of personal wants of the ‘Tai-pans’ and pursers.”

[*Factory refers to the premises that foreigners occupied as dwelling and office in Canton.]

Communication between the Chinese and the Europeans was mainly conducted through Chinese Pidgin English. An example of this language is illustrated below. In response to his employer’s inquiry about the safety of the bread at the house, the compradore replies:

Me no savey. Talkee that blead got spilum. My savey this hous blead all light.

The incident of the E-Sing bread poisoning occurred in Hong Kong 1857. The incident was a shock to the European residents in Hong Kong as it coincided with the outbreak of the Second Opium War (1856–1860). Chinese Pidgin English is a lingua franca created to facilitate cross-cultural communication. The main languages contributing to vocabulary and grammar of Chinese Pidgin English are Cantonese and English. A closer look at the pidgin reveals features similar to and distinct from Cantonese and English. While most words are derived from English, traces of an earlier power – the Portuguese are also evident. For example, forms derived from the Portuguese word saber ‘know’ can be found in many places where the Portuguese settled such as China. So, savey originates from saber in Portuguese. Words that are spelt with the letter ‘r’ is replaced by ‘l’, for example. blead and light. This substitution is common because Cantonese does not have the /r/ sound. Addition letters as in talkee and spilum indicate that some consonants like /k/ and /l/ attract extra syllables. The subject function of the first person pronouns can be expressed in multiple forms, like me and my in the example. However, like Cantonese, the subject in Chinese Pidgin English need not be expressed, as in the missing subject in Talkee that blead got spilum.

While the responsibilities of the compradores were heavy, through interacting with different people they also developed extensive social and business connections which allowed them to be an emerging social class in China. Many compradores became successful businesspeople and entrepreneurs who contributed significantly to the modernization of China in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The history of the word tael on the receipt of the Shanghai Municipal Council is also interesting. Tael, alongside mace, and candareen are derived from Malay tahil, mas, and kĕndĕri respectively. In Chinese, they are called 兩loeng2 (tael),錢cin4 (mace), and 分fan1 (candareen). In the past, they were also used as currency denominations. They are still used as units of weight in Hong Kong.

1. Hunter, William C. 1882. The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days 1825-1844. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co.