Located at the Pearl River (珠江) (Cantonese: zyu1 gong1, Mandarin: zhujiang) in south China, Canton 廣州 (currently romanized as Guangzhou) has been referred to by different names – 穗 ‘rice’ (Cantonese: seoi6, Mandarin: sui), (五)羊城) ‘City of (the Five) Rams’ (Cantonese: ng5 joeng4 sing4, Mandarin: wu yang cheng) and 花城 ‘City of Flowers’ (Cantonese: faa1 sing4, Mandarin: hua cheng). It is the capital city of Guangdong Provence (廣東省) and has long been a window to the world. In particular, the designation of Canton as the sole entrepot for foreign trade in 1757 positioned the city at the centre stage of global commerce.

The main water route western traders took to Canton was discovered by the Portuguese navigators in the late 15th and 16th centuries. Europeans began their voyages by rounding the Cape of Good Hope. They then travelled northeast to the Indian Ocean. Sailing eastward, they took passage of the Strait of Malacca and arrived at the Malay Peninsula. The next stop was the south China coast. Foreign ships first stopped briefly at Macau, where the Portuguese obtained licence for settlement from the Chinese government in 1557. At Macau, western traders would hire pilots to help them navigate up the Pearl River. Foreign ships could not enter Canton freely. Trading ships and their cargoes would be measured and charges paid at Lintin, a small island north of Macau, Then, at the Whampoa anchorage goods would be unloaded onto boats of varying sizes and sampans and taken to Canton.

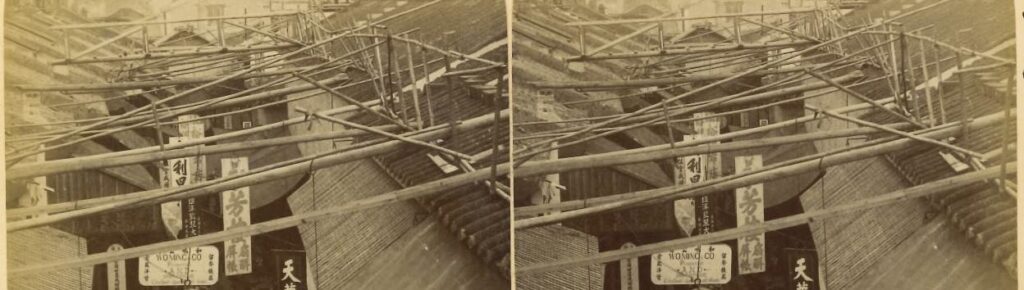

At Canton, foreigners, locally known as “foreign devils”, were subject to regulations restricting their personal freedom such as where they could live, work, visit, entertain, etc. While most Chinese lived inside the walled city, the foreigners were confined to an area around Western Suburbs (西關), outside and west of the city wall. The residences, offices, warehouses of the foreign traders, known as the Thirteen Factories (from Portuguese feitoria) or hongs in Chinese, was a neigbourhood fronted the Pearl River. The row of factories of the British, Americans, French, Swedes, etc., the hustle and bustle of the public square and streets, and the people living and working on the river became a constant scene that depicted the energy of the city in export paintings. After the First Opium War (1839–1842), many restrictions on foreigners were lifted or relaxed and the vibrancy of the Canton peaked. Entertainment in Canton was never lacking. North of the foreign factories or hongs were long and narrow streets where shops sold a wide range of products and provided different services. Newcomers to Canton might need help to navigate within the city. Grab a guidebook like the one below so you will not get lost.1

“The street running East and West at this point is called Factory Street (in Chinese 十三行街) and dives into the heart of the Western suburbs, whence in former days the mob was accustomed to come trooping down to surround and pillage the foreign dwellings. Parallel with Factory Street but further north, runs the finest and most fashionable thoroughfare in Canton, called in its eastern division, by foreigners Curio Street, or Physic Street, (by the Chinese Tseung Lan Kai 槳欄街), and in its Western half Howqua Street (by the Chinese, Shap Pat Pu, 十八甫). Howqua Street derives its foreign name from the residence situated therein of How-qua, the well-known head of the former guild of Hong Merchants, most of whom, indeed, with other wealthy individuals, occupy dwellings here.”

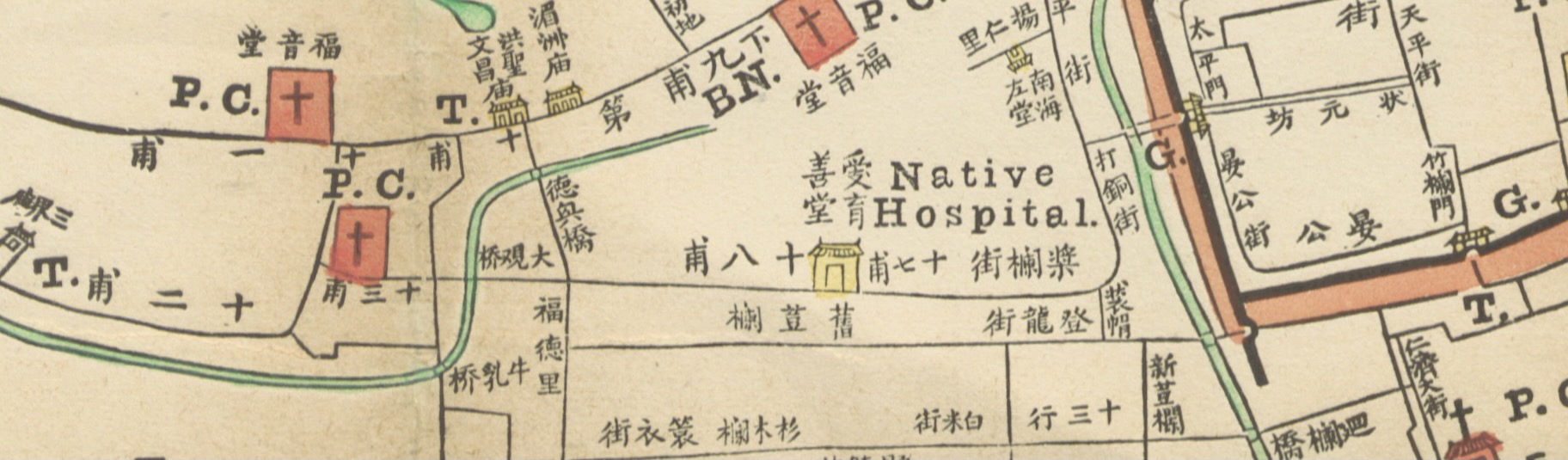

Shap Pat Pu (see the featured image) was one of the busiest commercial areas in Canton. Apart from shopping, Christians would have no difficulty fulfilling their spiritual needs. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions reported their work in South China for the year 1894–95 as follows.2

“Canton.—The work in the city was rather encouraging at the beginning of the year. We had one chapel of our own here, and in March the Christian Chinese bought a place at Shap Pat Po and opened a chapel under our supervision, but with no expense to us.”

The area called Shap Pat Pu was not only a busy marketplace but also the residence of many wealthy Chinese merchants or hong merchants. One of the residents was Howqua 浩官, whose Chinese name was 伍秉鑑 (Cantonese: ng5 bing2 gaam3, Mandarin: Wu Bingjian; 1769–1843). As described above, Howqua was the head of Ewo Hong (怡和行) and leader of Canton cohong. Hong merchants were appointed by the government and they acted as mediators between Chinese officials and foreign traders. Besides wealth, Howqua was also well-known for his trustworthiness and righteousness. Many Western traders like William C. Hunter (1812–1891) developed friendships with Howqua. Hunter arrived at Canton in 1825 at the age of 13 and resided there since then before returning to America in 1844. Recalling his life at Canton before the First Opium War, Hunter gave an example of how a conversation with Howqua (or Houqua) would have occurred.3 (Hunter 1882: 36-37)

Hunter: Well, Houqua, hav got news to-day?

Houqua: Hav got too muchee bad news. Hwang Ho hav spilum too muchee.

Hunter: Man-ta-le hav come see you?

Houqua: He no come see my, he sendee come one piece “chop.” He come to-mollo. He wantchee my two-lac dollar.

Hunter: You pay he how mutchee?

Houqua: My pay he fitty, sikky tousand so.

Hunter: But s’pose he no contentee?

Houqua: S’pose he, No. 1, no contentee, my pay he one lac.

The topic of their discussion was the overflow (hav sopilum too mcuhee) of Hwang Ho (黃河) or the Yellow River. The Man-ta-le who would come tomorrow was the Mandarin ‘Chinese official’. As one of the most influential Chinese merchants, Howqua would be expected to contribute significantly (two-lac dollar) to repair the damages caused by the disaster. Lac, more commonly spelt lakh, denotes the numerical value of 100,000 and is a unit used in India and other South Asia countries. Although the paper or “chop” demanded 200,000 dollars, being an experienced and clever merchant, Howqua would not readily comply with such extortion, or “squeeze” as known in pidgin English.

If you get the main point of the conversation but do not completely understand it, this is because Howqua and Hunter were using Chinese Pidgin English – a business language comprising vocabulary from English, Chinese, Portuguese, Malay, Hindi, and other languages. The grammar of pidgin English was a fusion of English and Cantonese – the local dialect of Canton. Pidgin English was the most common means of communication at the time and learning it was important as the international community in Canton depended on it to get things done.

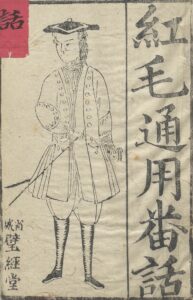

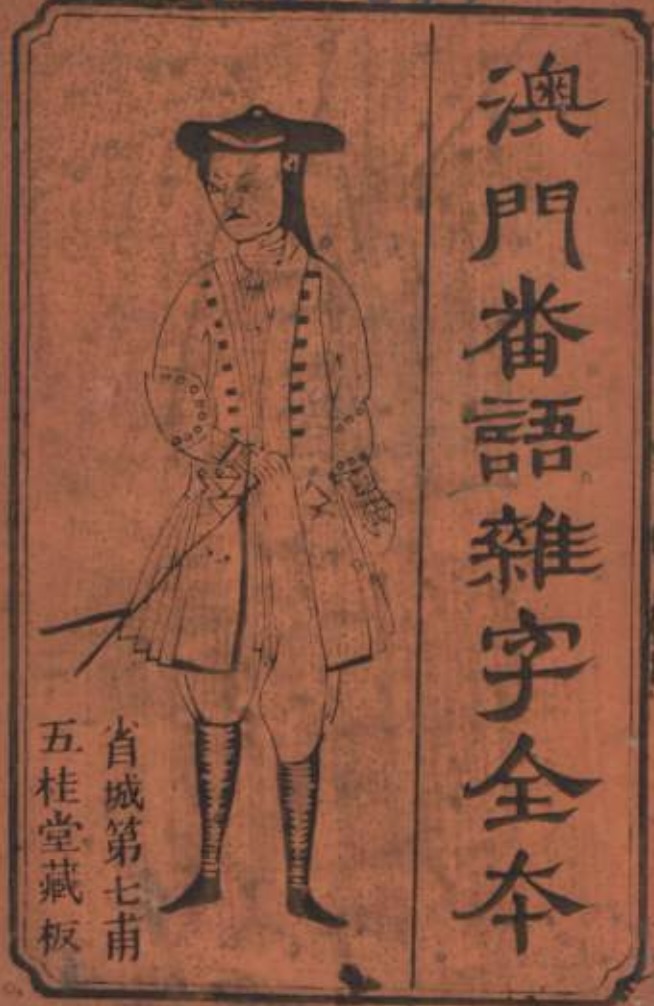

Two types of pidgin phrasebooks were available for purchase in Canton. Their titles were 《澳門番話雜字全本》(A Compendium of Assorted Phrases in Macau Pidgin) for communicating with Portuguese-speaking people and 《紅毛通用番話》(The Common Language of the Red-haired People) for English-speaking people.4, 5 You could buy the first book, and possibly the second one too, at the Seventh Po/Pu (第七甫) in the commercial area. Learning the several hundred words and phrases in these booklets would give you a head start to mingle and do “pidgin” (business) with the foreigners. One caveat: all foreign words in these phrasebooks were transcribed in Chinese characters, so make sure you could read Chinese or find someone who would teach you.

1. Mayers, Wm. Fred, N. B. Dennys & Chas. King. 1867. The Treaty Ports of China and Japan. A Complete Guide to the Open Ports of Those Countries, Together with Peking, Yedo, Hongkong and Macao. London: Trübner and Co.; Hongkong: A. Shortrede and Co.

2. Eighty-Fifth Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. 1895. Published by the Board.

3. Hunter, William C. 1882. The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days, 1825-1844. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co.

4. Williams, Samuel Wells. 1837. Gaoumun fan yu tsa tsze tsuen taou, or A complete collection of the miscellaneous words used in the foreign language of Macao. 2. Hungmaou mae mae tung yung kwei hwa, or those words of the devilish language of the red-bristled people commonly used in buying and selling. Chinese Repository 6, 276–279.

5. Li, Michelle & Stephen Matthews. 2016. An outline of Macau Pidgin Portuguese. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 31:1, 141–183. doi 10.1075/jpcl.31.1.06li