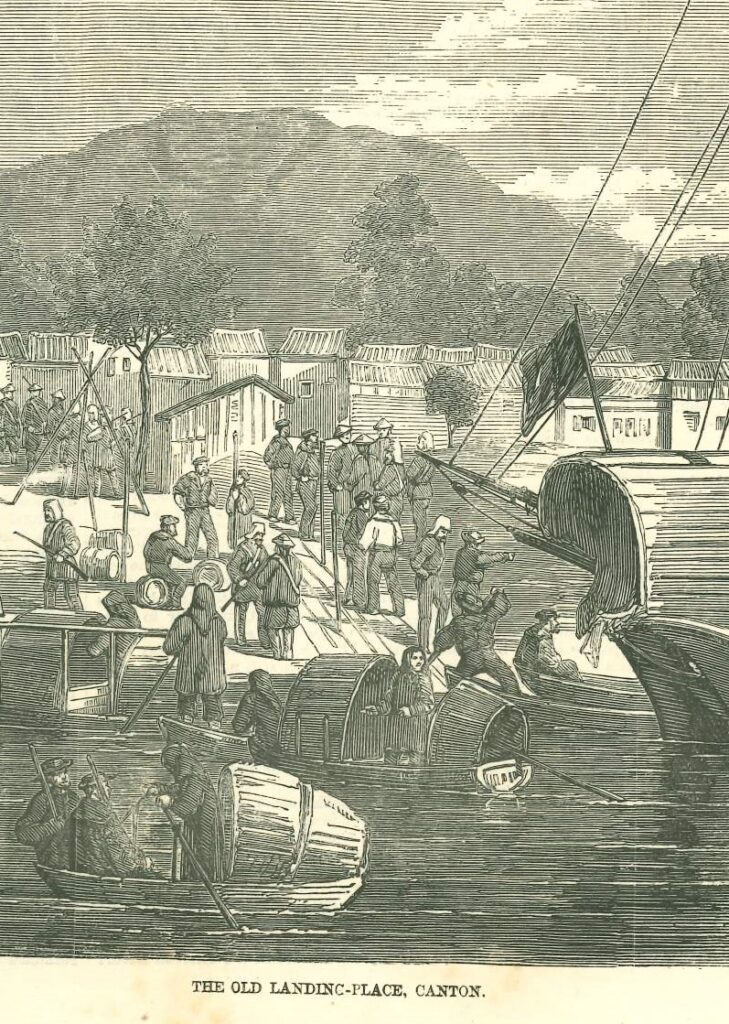

For most of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and the early period of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), China adopted a series of policies collectively referred to as sea ban (haijin 海禁) which essentially disconnected itself from the maritime world. Chinese people were prohibited from going to sea and privately trading goods with foreign countries. However, such policies were counterproductive as illegal trade, smuggling, and piracy continued. While forbidden from landing in mainland China, foreign traders used the Portuguese settlement – Macau – as their anchorage for international maritime commerce. The loosening of the sea ban and the permission to trade in Canton (廣東) were turning points in Chinese and world history. By the early 18th century, foreigners were allowed to stay in Canton and built their premises known as the “thirteen factories” fronting the Peral River. In 1757, the monopolistic Canton System meant the centralization of Western trade in the Pearl River area.1 Canton, thus, became a hub that gathered people of various ethnic and linguistic origins.

A challenge for the people trading and residing in Canton was communication. It was this context that gave rise to the development of a new language in the 18th century. This language has been referred to by different names in Chinese and English. Here, I use the term Chinese Pidgin English because it is more well-known to the public and academia. As the name suggests, Chinese, essentially Cantonese, and English play major roles in its formation. A pidgin is a language that serves as a lingua franca to enable people speaking different languages to understand each other. A pidgin is employed for specific situations only, such as trade and domestic service. Since the domains of use are limited, a pidgin therefore does not require a full-fledged lexicon. Moreover, the speakers’ backgrounds would result in variations in usage. The most widely accepted etymology of the word pidgin is the English word business.

Besides Chinese Pidgin English, people also used other terms to call the language in different periods and places. Let us take a look at some of the terms. Some terms focus on the overall linguistic affiliation of the pidgin, for example, 番話 (Cantonese: faan1 waa2) means ‘foreign speech’, 鬼話 (Cantonese: gwai2 waa2) ‘devil’s speech’, and 英語 (Cantonese: jing1 jyu5) ‘English language’. These terms indicate that the lexicon of the pidgin is overall English-based. In old Chinese custom, the words 番 ‘foreign’ and 鬼 ‘devil’ refer to anything foreign. Therefore, at that time foreigners were referred to as 番鬼 (Cantonese: faan1 gwai2), literally meaning ‘foreign devil’. Another term 紅毛 (Cantonese: hung4 mou4), the red-haired people, was also used to call the foreigners. A pidgin English phrasebook available in Canton was entitled 紅毛通用番話 (Cantonese: hung4 mou4 tung1 jung6 faan1 waa2) ‘The Common Foreign Language of the Redhaired People; A foreigner speech commonly used with the red-haired people’.2

Other terms name the pidgin according to where it was spoken, some examples are 廣東番話 (Cantonese: gwong2 dung1 faan1 waa2) ‘Canton foreign speech’ and 洋涇濱英語 (Cantonese: joeng4 ging3 ban1 jing1 jyu5; Mandarin: yáng jīng bāng yīng yǔ). In English literature, we can find names such as “Canton jargon” or “Canton English”. As the pidgin developed in 廣東 (Canton), using this as part of the pidgin’s name was a natural choice. Shanghai became a treaty port after the First Opium War and this status attracted traders from all nationalities to seek fortunes there. As a result, the already well-established pidgin spoken in Canton was adopted as the usual medium of Sino-Western communication. 洋涇濱 was the name of the creek that separated the British Settlement and the French Settlement in Shanghai. Later, this name was adopted to stand for pidgin English.

People may also call a language based on their perception of the language. Criticisms abound on the inadequacy and impurity of the pidgin because it was generally regarded as neither Chinese nor English. As a result, it was often described as a random mixture of different languages used by uneducated people, especially the Chinese in Western literature. Entering the early 20th century, Chinese gentlemen or elites also regarded pidgin as 蹩腳英語 (Cantonese: bit6 goek3 jing1 man2) (蹩腳 means ‘low quality’, ‘clumsy’) and felt offended when being addressed in this manner. The negative attitude towards Chinese Pidgin English was largely due to a superficial understanding of its evolution and usage. As a trade language, pidgin English was employed to handle transactions from as little as a few coins to as large as a million dollars. Therefore, the pidgin must have norms that allow speakers to achieve mutual understanding. Numerous sources indicate that pidgin English was spoken by anyone, regardless of nationality, who needed a common language for communication.

Although only spoken for about 200 years, Chinese Pidgin English underwent different phases that characterized its vocabulary and grammar. Macau was the first place in southern China to have constant interaction with Westerners, particularly Portuguese. As a result, the Portuguese language or varieties of Portuguese was the main medium of interethnic communication. In fact, accounts of Chinese Pidgin English almost always mention the existence of Portuguese words. The sentence below illustrates the presence of Portuguese words in Chinese Pidgin English. In this example, the author described the language of his Chinese acquaintances as a “broken and mixed dialect of English and Portuguese”.3

He no cari China man’s Joss, hap oter Joss.

‘that man does not worship our god, but has another god.’

Other surviving pidgin English expressions include can do, which means ‘It could/would be done.’ The “can-do” spirit, sometimes used to characterize Hong Kong, refers to the determination to face problems and complete something. The negative form no can do, as shown in the featured image,was also a popular expression. Originally written in English, the song No Can Do was translated into other European languages such as Swedish. If you learn Chinese Pidgin English, can do and no can do are the top 10 phrases you should know. In 1839, the American frigate Colombia under the command of Commodore George C. Read laid at anchor in Macau before proceeding to Canton. While visiting the Chinese temples in the Portuguese settlement, the crew asked an attendant of the Chinese gods if he could tell them their fortunes. At this time, a priest said 4

Other pidgin English expressions we occasionally see include can do, which means ‘it could/would be done.’ The “can-do” spirit, sometimes used to characterize Hong Kong, refers to the determination to face problems and complete something. The negative form no can do, as shown in the featured image,was also a popular expression. Originally written in English, the song No Can Do was translated into other European languages such as Swedish. If you learn Chinese Pidgin English, can do and no can do are the top 10 phrases you should know. In 1839, the American frigate Colombia under the command of Commodore George C. Read laid at anchor in Macao before proceeding to Canton. While visiting the Chinese temples in the Portuguese settlement, the crew asked an attendant of the Chinese gods if he could tell them their fortunes. At this time, a priest intervened said 4

“Hai yah! no can do.”

The crew inquired why it could not be done. The priest explained that since the Chinese gods did not know foreigners, he couldn’t do fortune-telling for them. In the priest’s own words,

“spose my speakee that god do Fanqui pigeon—he god no can do—he no sabé one Fanqui.”

Hai yah (哎吔 ai1 jaa3) is a Cantonese exclamation of surprise, annoyance, disapproval, etc. depending on the context. Another Cantonese word is Fanqui (番鬼 faan1 gwai2), meaning “foreign devil”. Pidgin English is sometimes spelt Pigeon English; therefore, in the sentence pigeon refers to ‘business’.A final piece of evidence of Portuguese presence is the word sabé, which is derived from saber ‘to know’. Different forms of saber exist in pidgin and creole languages that are lexically based on Portuguese, for example, the creoles in Malacca and Macau. Given the close commercial and cultural connections between Macau and Canton, it is highly possible that Portuguese words such as the ones mentioned above constitute part of the early vocabulary of Chinese Pidgin English.

1. Nield, Robert. 2010. The China Coast. Trade and the First Treaty Ports. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing.

2. Bolton, Kingsley. 2003. Chinese Englishes. A Sociolinguistic History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

3. Noble, Charles Frederick. 1762. A Voyage to the East Indies in 1747 and 1748. Containing an account of the islands of St. Helena and Java. Of the city of Batavia. Of the government and political conduct of the Dutch. Of the empire of China, with a particular description of Canton, and of the religious ceremonies, manners and customs of the inhabitants. London: Printed for T. Becket and P. A. Dehondt.

4. Read, George C. 1840. Around the World: A Narrative of a Voyage in th East India Squadron, under Commodore George C. Read. By an officer of the U.S. Navy. Vol. II. New York: Charles S. Francis.