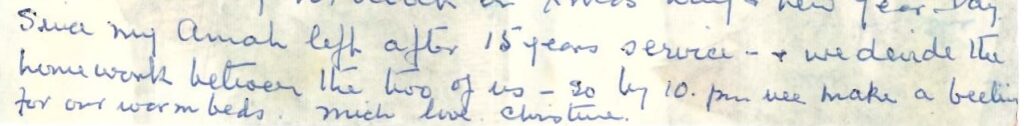

Female domestic workers occupy an important role in the family. During the rule of the East India Company and the British government, the female servants who cared for children in European families in India were called ayahs, i.e., nursemaids. The Hobson-Jobson dictionary of Anglo-Indian words suggests that ayah is derived from the Portuguese aia ‘a nurse, or governess’.1 In 19th and 20th-century China, Hong Kong, and Macau, the child carers were known as amah, or 馬maa5姐ze2 in Cantonese. The dictionary also suggests a Portuguese source ama for amah. The featured letter above was sent from Macau to Canada in 1973. Overall, the letter an ordinary exchange of information. However, at the end of the letter, the writer tells us a change in her family: “Since my Amah left after 15 years services – we divide the housework between the two of us – so by 10 pm we make a [bedding] for our warm beds.” This short note briefly shows the duties of an amah in the 20th century, namely taking care of the children, cleaning the house, washing the clothes, or other domestic tasks assigned by the employers. For families with a larger number of servants, the amah might only be required to care for the children, while other duties would be performed by the house boy, the cook, the coolie, and so on. Like this amah, many Chinese amahs would have retired by the 1970s.

While started as a lowly job, the amah as a profession gradually developed into an identity symbolizing independence, daring, and loyalty. This transformation is best exemplified by the Chinese women who travelled from China to the the Straits Settlements for new opportunities. In the 1930s, the decline in the silk industry in the Guangdong province of China resulted in many factory workers, especially women, losing their jobs. Many went to Hong Kong, Macau, and 南naam4洋joeng2 to seek job opportunities. Some women worked in construction sites and factories; others worked as amahs in the households of foreigners and local people. These domestic workers were addressed as 馬maa5姐ze2 in Chinese. These women left their countries alone and found their way out in the new environment alone. They developed a strong sense of independence and determination that many chose to become 自zi6梳so1女neoi2, or self-comb women who vowed to 梳so1起hei2 ‘comb up the hair’, that is, taking a vow of celibacy. It is easy to identify the amahs because they wore a unique outfit. Typically, they wore a white top and black trousers. This appearance gave them the name ‘black-and-white’ amahs. They were long, black hair in a braid or a bun. Like the amah mentioned in the letter, amahs often served in the same family for a long time. After retirement, many unmarried amahs chose to live in vegetarian houses (齋zaai1堂tong2) or 姑gu1婆po4屋uk1 (houses bought by the amahs) after retirement. Some returned to their hometowns.2

The international communities in Shanghai also employed amahs, like the postcard on the right which comes with a message saying: “This P.C. is a picture of the Chinese Amahs who take care of the foreign children – They usually take them to the P. Gardens in summer when it is cool.” As the amahs spent most of their time interacting with the European children, their communication was achieved through Chinese Pidgin English. This is a language the Chinese and Westerners employed in order to overcome the language barrier. Shanghai was not the first place where Chinese Pidgin English used because dating back to the 18th century the language was already used as a lingua franca in Canton (now Guangzhou). The designation of Shanghai as one of the newly opened treaty ports in 1842 turned Shanghai into an international settlement. This is the context in which Chinese Pidgin English entered the scene. Started as a business language, the use of Chinese Pidgin English extended to domestic services as the observation from Clark shows below.3

“Amahs have fair opportunities of acquiring the “pidgin” talk, and if their stock of English words is not so large as that of a “boy’s,” this is to be accounted for by the fact that their sphere of life confines them more indoors, and excludes them from mixing up with the bustle of the town. Some of them, however, succeed in learning “pidgin” English to a creditable degree; and we noticed those especially experts who had served for a number of years in the houses of missionaries; and if the latter happened to hail from the States they even somehow managed the acquire the nasal twang, and some of their Americanisms. As for the rest, an amah’s vocabulary is restricted to the “pidgin” equivalents regarding babies’ clothing, babies’ food, and odds and ends making up the boudoir of sleeping apartment of her “mississee.”

Some households might employ different types of amahs for different duties, for example, there were baby amahs, wash amahs, and sew amahs. Martin Booth (1944-2004), the son of a civil servant, spent his childhood in Hong Kong from 1952 to 1964. In his book Gweilo: A memoir of a Hong Kong Childhood, we can find interesting descriptions of his adventures in the city and interactions with the Chinese people. Booth recalls an interaction between his mother (missee) and Ah Choy (amah). Below is how Ah Choy introduces herself in the job interview.4

“Me name Ah Choy,’ she said softly. ‘I good wash-sew amah for you, misee.’ She saw me standing by the window. ‘You young master?’ My mother introduced me. ‘Ve’y han’sum boy,’ Ah Choy replied, no doubt perceiving my blond hair and anticipating many brief daily encounters with good fortune. ‘Good, st’ong boy. Be plentee luckee.’ … ‘Where did you go in the war?’ my mother enquired. ‘I go quick-quick China-side,’ she replied. ‘Master go soljer p’ison Kowloon-side. Missee and young missee go war p’ison Hong Kong-side. Japan man no good for Chinese peopul.”

The language Ah Choy uses is Chinese Pidgin Chinese. Some characteristic features of the language can be seen in this short presentation. There are different types of omissions, including the verb “to be”, (Me name Ah Choy, You young master?), the subject, (Ve’y han’sum boy), and the past tense marking on verbs. Phonetically, some English-language sources show a substitution of “l” for “r” as Cantonese does not have the “r” sound, but Ah Choy seems to leave out the “r” sound altogether. Adding side after place names is based on a similar structure in Cantonese.

Because of the increased accessibility to education and availability of new types of jobs, there were very few working Chinese black-and-white amahs in Hong Kong by the 1970s. However, the need for children carers has not ceased, what has changed is the source of supply. In Hong Kong, Filipino and Indonesian domestic helpers, usually referred to as 姐ze4姐ze1 ‘sister’, have replaced the traditional amahs. Despite differences in name and time, some domestic helpers develop strong bonds with the families they work for. Such bondings may last even after they leave the family.

1. Yule, Henry and Arthur Coke Burnell. 1886. Hobson-Jobson Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms. London: John Murray.

2. Gaw, Kenneth. 1988. Superior Servants: The Legendary Cantonese Amahs of the Far East. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

3. Clark, J.D. 1894. Sketches in and around Shanghai, etc. Shanghai: Shanghai Mercury and Celestial Empire Offices.

4. Booth, Martin. 2004. Gweilo: Memories of a Hong Kong Childhood. London: Doubleday.