The Age of Discovery, from the 15th to 17th century, created unprecedented opportunities for people of different cultures to interact. Curiosity, wealth, and domination were the main reasons people risked their lives to explore uncharted waters and territories. European exploration would not have been successful without proper seagoing vessels.

Before the 15th century, European sailing vessels mainly navigated within local or regional waters. The Mediterranean, for example, was the maritime commercial hub and centre of cultural exchange for different civilizations for thousands of years. To reach the east, traders normally travelled overland. However, overland routes to eastern markets became difficult to access due to the rise of the Ottoman Empire in the 14th century. This gave rise to the search for alternative routes to the east. Two empires – Portugal and Spain – thus began investing in sea routes. The first milestone of the Portuguese navigators occurred in 1488, when Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in Africa, thereby revealing the route to the East Indies. The landing of da Gama in Calicut in 1498 started the era of Portuguese India; in 1511 the occupation of Malacca brought the Portuguese to the Far East. China was every trader’s dream. In 1557, the Portuguese were the first Europeans granted the right to settle in Macau in southern China in recognition of their contribution to combat piratical activities. Acting as middlemen, the Portuguese traders then established the lucrative Canton-Macau-Nagasaki route. The Spaniards would leave their marks on the other side of the globe. Originally looking for a route to the Far East, Christopher Columbus led the Spanish fleets to cross the Atlantic and found the Americas (the New World) instead. Spanish territorial occupation subsequently covered the North, Central, and South Americas. The height of Spanish navigational success was the first circumnavigation of the Earth (1519–1522) – sailing across the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans – led by Ferdinand Magellan and Juan Sebastián Elcano. One of the consequences of the exploration was Spanish colonial rule in the Philippines lasting from 1565 to 1898.

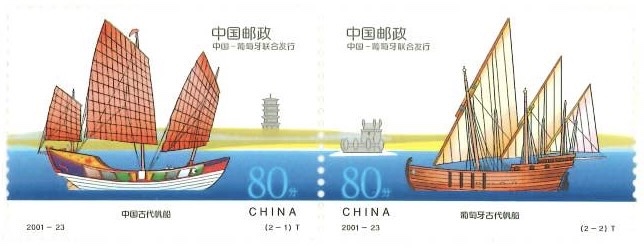

All these European explorations were accomplished using sailing vessels propelled by wind. The period from at least the mid-16th to mid-19th century is known as the Age of Sail, which characterizes not only the myriad sailing vessels but also advances in shipbuilding. Caravel was an important type of vessel used by the Europeans for early long-distance voyages. For example, two of Columbus’s ships – Pinta and niña – were caravels. Though small by modern standards, the speed of the vessel was significantly enhanced by their sleek body and lightweight. Moreover, the use of lateen sails allowed greater maneuverability. These advantages made caravels a popular type of vessel. As travel distance increased, round caravels were built to expand cargo space. Later designs such as square-rigged masts and a bowsprit with spritsail aimed to speed up the vessel. By the 15th and 16th centuries, faster, stronger, armed, multi-decked ships known as carracks (nau in Portuguese, nao in Spanish) and galleons were built especially for battles and long-distance trade. Columbus’s flagship Santa Maria was a nao.

The term junk or 帆船 in Chinese refers to many types of coastal and river vessels used for carrying cargo, fishing, housing, etc. The character 帆 (Cantonese pronunciation: faan4) means ‘a sail’ and 船 (syun4) ‘a ship.’ A signature feature of Chinese junks is the watertight bulkheads that prevent water from overflowing to other compartments if the vessel leaks. These interior compartments also help strengthen the stability of the junk while sailing. A typical junk has one to three masts, has a high poop deck, a transom stern, and a rudder mounted at the stern. The most iconic part of a junk is the lug sails. Hung from a yard, these four-sided and fully battened sails are usually linen cloth or mat. Unlike the square-rigged sailing vessels of the west, hoisting and reefing of the sails required a small crew.

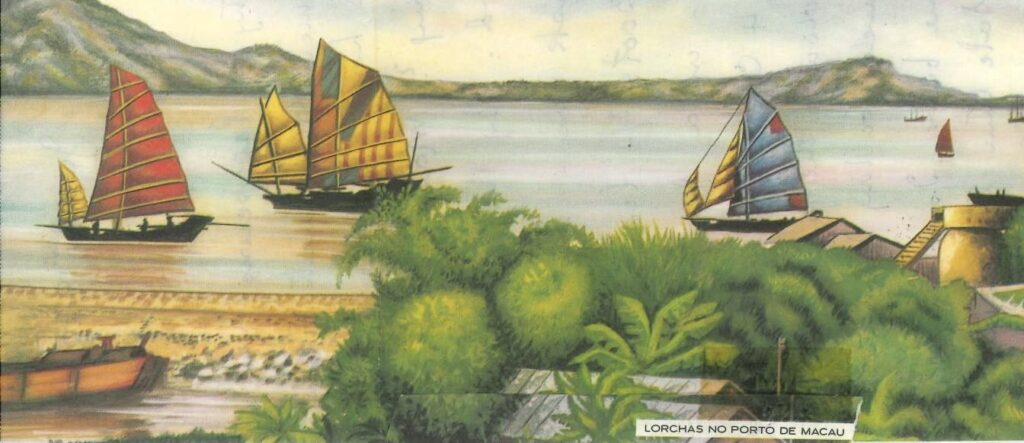

The featured image above, titled “LORCHAS NO PORTO DE MACAU” ‘Lorchas in the port of Macau’, shows a special type of vessel. Though categorized as junk, a lorcha is neither eastern nor western in construction but a combination of both shipbuilding cultures. The craft is referred to by several Chinese appellations: 老閘船 (lou5 zaap6 syun4), 鴨尾船 ‘duck-back-ship’ (aap3 mai5 syun4) or 鴨屁股 ‘duck’s bottom’ (aap3 pei3 gu2). Giles (1886: 138) mentions the name 划艇 ‘paddling boat.’1

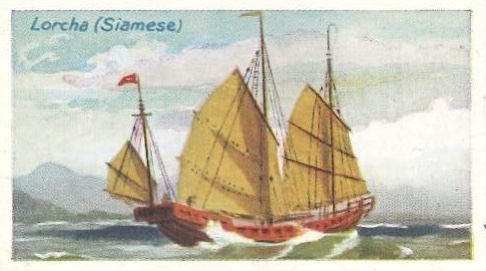

Lorcha is a hybridization of eastern and western shipbuilding wisdom. The hull of the lorcha adopts the lines of European ships, but the stern, rudder, and rigging are of the Chinese type. It is usually made of camphor wood or teak, with a size ranging between 40 and 150 tons but can also be as big as 300 tons.2 A jib could sometimes be seen in old pictures. The design of the lorcha not only makes it travel faster than traditional Chinese junks, but it also has greater cargo capacity. In addition to being employed as merchant ships, lorchas equipped with guns were used as fighting ships to combat piratical activities, or as convoys for escorting merchant ships. The crew of a lorcha might also be mixed – usually a European captain, particularly Portuguese, and a mainly Chinese crew.

Some suggest that lorchas were first built in Macau. However, the Hobson-Jobson glossary (1886) indicates that the word lorcha (or lorch)appears as early as 1540 in the writing of Fernão Mendes Pinto, who travelled from Portugal to Africa and the Orient between 1537 and 1558.3 In Pinto’s autobiography, there are mentions of lorcha while the writer is travelling in Southeast Asia and China. While navigating along the coast of Champa (present-day central and southern Vietnam), Pinto and his companions spotted some suspicious objects on the water, the captain of the lorcha then warned the crew to arm themselves. The examples below are based on the translation of Rebecca D. Catz.4

“What we are up against is nothing but a thief who is out to attack us because he thinks that there cannot be more than six or seven of us here, which is how we usually sail on these lorchas.” (p. 83)

Later, anchoring at the Gulf of Cochinchina, Pinto writes:

“And at nightfall, with the approval of all the soldiers, before making any other move, he [Antonia de Faria] ordered them to transfer to the better of the two ships, since the lorcha in which he had set out from Patani was taking on too much water; and this was done without any further ado.” (p. 87)

Patani was a historic Malay region located in the south of present-day Thailand and on the east coast of the Malay Peninsula. Based on Pinto’s writing, lorchas were used in Chinese waters and Southeast Asia. G.R.G. Worchester (1890–1969), a trained sailor, developed a deep interest in Chinese watercraft while serving as a River Inspector in the Marine Department of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service. In his book The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze (1971), he suggests that the lorcha could have originated in Malaya, where junks were being modified into this hybrid craft.

Piracy in the South China Sea was a constant problem for the Chinese government. Joint anti-pirate operations, first with the Portuguese, then the British and American navies, continued until the early 20th century. Possessing expert knowledge insailing and fighting machines, the pirates no doubt would have known the effectiveness of the lorchas.

Born in Edinburgh, James Grant (1822–1887) joined the military briefly before devoting himself to writing. He was a prolific novelist who wrote many works about Scottish history and the military. For instance, the short story “The voyage of the ‘Bon Accord’” tells about a piratical attack in southern China. While in Macau, the captain of Bon Accord hires a Chinese pilot who turns out to be the pirate Long Kiang.5 The captain spots a suspicious vessel and says,

‘It is a lorcha—full of men, and evidently dodging us—a Macao lorcha, too’

The captain turns to the Chinese pilot who replies:

‘Si—si—yaas—senhor,’

‘That piecey boat makey fightey if you meddle with her’

The Chinese pilot first speaks in “the broken lingo peculiar to Macao” – Si—si—yaas—senhor. In Portuguese, si means ‘yes’ and senhor means ‘sir, mister’. It is not clear what yaas intends to mean. The pilot then uses “pigeon English” (also pidgin English) – a means of communication developed in Canton, China between Chinese and foreigners. The first clause of the pidgin sentence contains some typical features of pidgin English. These include that in place of the; the use of the classifier piecey before a noun; makey (from English make) to introduce action; and the insertion of an epenthetic vowel -ey after certain sounds, as in piecey, makey, and fightey. The second clause is simply standard English.

Despite the mysterious origin of the lorcha, memories of the vessel seem inseparable from Macau. In the olden days, you would find numerous lorchas gathered near Rua das Lorchas (火船頭街) at the Inner Harbour. Interestingly, the Chinese name of the street indicates a later ship type – 火船, literally ‘fire ship’, i.e., steamer. Continue walking southward, you will find a Portuguese restaurant named after this hybrid vessel. Not far away is the famous Temple of A-Má (媽閣廟). The Macanese community of Macau created a dish called Amargoso Lorcha ‘stuffed bitter melon’. To prepare the dish, slide the amargoso ‘bitter melon’ into half such that its shape resembles that of a lorcha. Prepare the stuff by mixing minced pork and other ingredients such as onion, garlic, tomato paste, balichão (a prawn sauce used in Macanese dishes), etc. Fill the amargoso with the pork stuffing, and finally simmer for half an hour.6

For Hong Kong, the incident on a lorcha named Arrow marked the beginning of the Second Opium War (1856–1860), which resulted in the cession of Kowloon peninsula south of Boundary Street to Britain in the Convention of Peking of 1860.

1. Worchester, George R.G. 1979. The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze. London: Naval Institute Press.

2. Giles, Herbert A. 1886. A Glossary of Reference on Subjects Connected with the Far East. (second edition). Hongkong: Messrs. Lane Crawford & Co.

3. Yule, Henry and Arthur Coke Burnell. 1886. Hobson-Jobson Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms. London: John Murray.

4. Pinto, Fernão Mendes. 1583. The Travels of Mendes Pinto. (Translation of Peregrinaçam)Edited and translated by Revecca D. Catz. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

5. Grant, James. 1882. “The voyage of the ‘Bon Accord’” in The ‘Scots Brigade’ And Other Tales. London: George Routledge and Sons.

6. Macanese Recipes: Amargoso Lorcha. https://macaneserecipes.org/amargoso-lorcha/