In the last post (12. Chin-chin joss), the object of chin-chin ‘worship’ can be a joss, that is, in Chinese tradition a god, goddess, or deity.The word is considered to be connected with the Portuguese word deus,meaning ‘God’. In Chinese Pidgin English, joss can form new words denoting Chinese and Western religious concepts and activities, such as chin-chin joss. Other religious concepts and objects include: joss house is a church or a temple, joss house man is a priest or missionary, joss pidgin refers to Chinese or Western religious matters, activities, or ceremonies. Chinese worshippers burn joss sticks, incense sticks, and joss paper,spirit/hell money for the dead, gods/goddesses, or idols. In China, there are different joss pidgin ‘religious businesses’, big and small, throughout the year. The word pidgin is also used in the sense of ‘business’ and is believed to be derived from how the Chinese pronounced the word business. While visiting the city of Canton, A European notices the burning of joss paper and describes it thus:1

“In front of most of the cottage-doors, “Joss-PAPER” was burning, composed of silver tissue-paper in the shape of shoes; that is to say, not the article with which you are wont to decorate your feet, but in form similar to the ingots cast for the currency of the nation; —of these more by-and-by. These bundles of Joss-paper are sold, strung upon strings, at something like sixpence a hundred. Of course there are different qualities, some cheaper, some more expensive.”

All these expressions with the word joss are recorded in Chinese Pidgin English, a new language that emerged in the context of the contact between the Chinese and Europeans. After the arrival of the Portuguese in Canton (now Guangzhou) to establish commercial relations in the 16th century, other Europeans followed suit. A difficulty they faced was a communication barrier, as a result, Chinese Pidgin English, whose linguistic inputs came mainly from Cantonese and English, was developed in Canton in the 18th century as a lingua franca for cross-cultural communication. The language was still sporadically spoken in Hong Kong until the 1960s/70s.

The Chinese New Year is an important festival for the Chinese. During this time, one of the activities is to go chin-chin joss in order to obtain joss’s blessings for the new year. The “boy” (male servant) of the European requests to leave his work so that he can worship joss in the Chinese New Year.1

Boy: Master, belong my chin-chin you. Just now my wantchee makee go that city side, makee chin-chin Joss.

European: What good will it do you, boy?

Boy: Good, my no sarby; belong olo custom pidgin, any man must wantchee go chin-chin Joss new year tim.

Chinese Pidgin English contains linguistic features based on Cantonese and/or English. Let us figure out what the “boy” is saying. The meaning of chin-chin varies depending on the context. The first instance of chin-chin means ‘to beg, request’, while the second instance (chin-chin Joss) means ‘to worship’. In addition to joss, another word of Portuguese origin is sarby. In Portuguese, saber means ‘to know’ and in Chinese Pidgin English there are different orthographic forms including sarby, sabe, savvy, and so on. Olo (from old) custom pidgin expresses traditional practices. Chinese Pidgin English has a limited vocabulary because it was used in situations where cross-cultural communication was required. Moreover, many words have multiple meanings and must be interpreted according to the context, for example, chin-chin. Another example is my. In English, this is the first person possessive form, but in the pidgin, as you can see in the example, my has an additional function, namely being the first person subject pronoun.

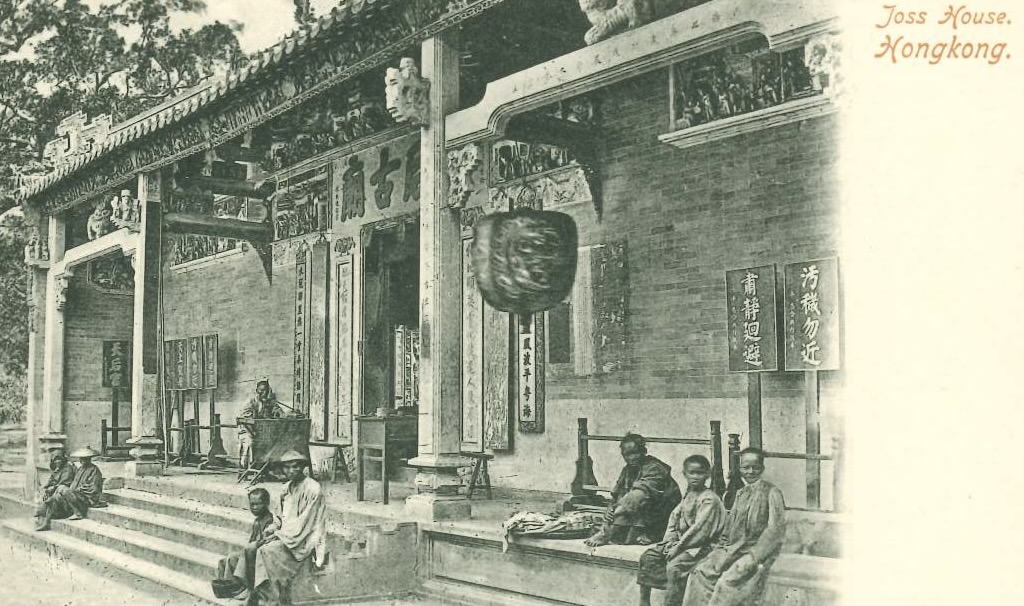

An important joss in Hong Kong is天tin1后hau6 (Tin Hau ), who is revered by fishermen and seafarers. In the early days of Hong Kong, fishing was a major industry and a large number of people lived on boats. As Tin Hau is well-known for protecting seafarers and safeguarding them for safe passages, numerous Tin Hau temples, big or small, were built near coastal Hong Kong, for example, Shau Kei Wan, Wan Chai, Causeway Bay, Yau Ma Tei, and Lantau Island to name just a few. The oldest of these temples is said to be the Tin Hau Temple at Joss House Bay (大daai6廟miu2灣waan1, meaning ‘Great Temple Bay’) in Sai Kung. Every year, worshippers bring offerings to the temples to celebrate the birthday of Tin Hau on the 23rd day of the third lunar month. The temple is now listed as a Grade 1 historic building.

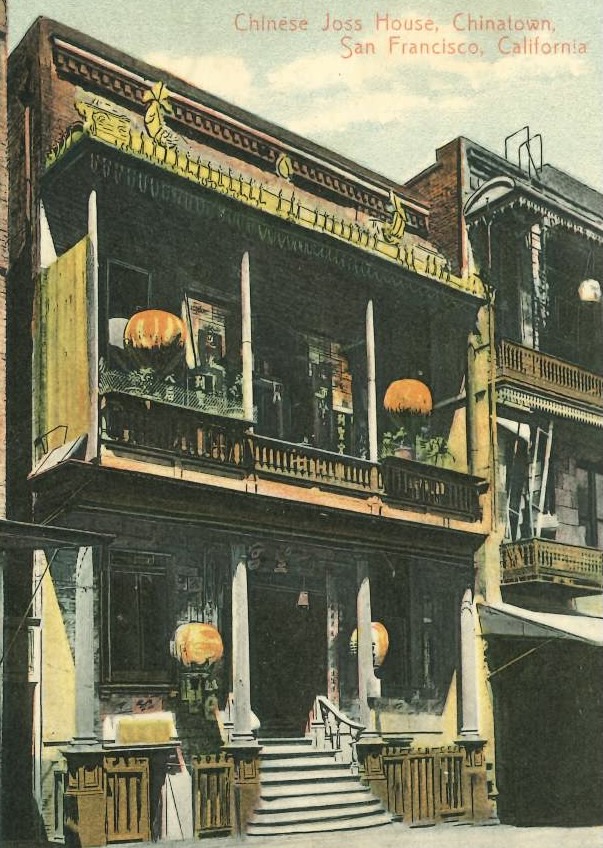

Early generations of overseas Chinese in America, Australia, and Canada continued to observe many traditional practices and festivals, including lion dance, dragon dance, Chinese New Year, and idol worship. In the Chinatowns where Chinese immigrants settled in the 19th century, it was easy to find joss houses like the one shown on the postcard. A commission report on the lives of Chinese immigrants in British Columbia states that the Chinese merchants purchased merchandise like: “Rice, tea, oil, liquors, tobacco, dry goods, chinaware, drugs, silk goods, paperware, books and stationery, matting, clothes, shoes, opium, Joss-paper and sticks.”2 This list shows that joss paper and joss sticks, essential items for worshipping gods, were as essential as other ordinary consumables to the Chinese. The report also describes the interior of a joss house in San Francisco.

“There are some fine large temples in San Francisco, besides a number of smaller ones. The “Eastern Glorious Temple” is the Joss-house we now enter. This temple is owned by Dr. Lai Po Tai, who has a large practice among the whites. In the central hall are three fierce looking idols in the midst of a lot of gilding and ornamentation, their stomachs protruding in accordance with the Chinese ideal of manly beauty. The central figure is “the Supreme Ruler of the Sombre Heavens,” and on his right is “the Military Sage,” and on the left “the Great King of the Southern Ocean.

“In the courts of the temple the priests sold candles, and little spills of timber for burning before the idols, and written prayers and charms, and there were various means of enquiry of the oracle after you had prayed, such as two pieces of timber, each with a flat and round surface, and if they fall in a certain way your desire will be granted.”

In the Southern Min (閩man5南naam4話waa2) spoken in Taiwan, these pieces of timber are called pue (桮 or 杯). Throwing pue, called pua̍h-pue (跋桮 or 跋杯), is a divination in Taiwan to ask for guidance from the divine.

1. Anonymous. 1860. The Englishman in China. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co.

2. Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration. Report and Evidence. 1885. Ottawa: Printed by order of the Commission.