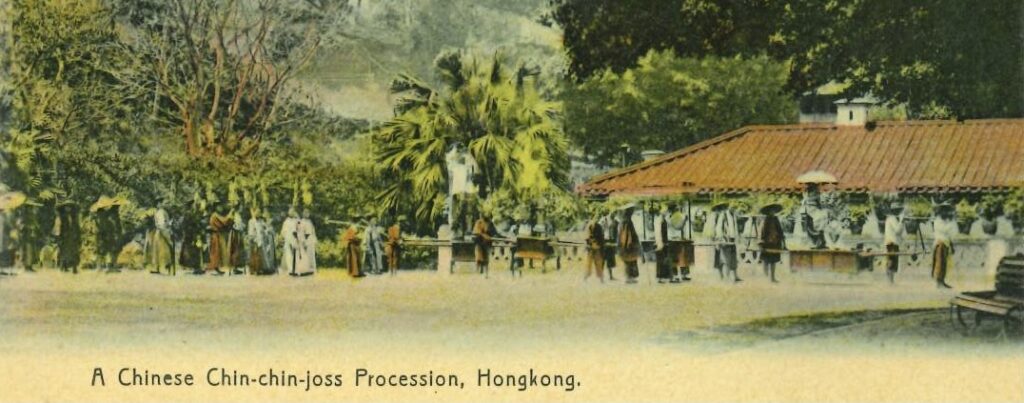

The Hobson-Jobson Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms (1886) is an essential collection of words of Asian origins in English. The dictionary compilers, Henry Yule and Arthur Coke Burnell, meticulously explain the Asian words that entered the English language through the trade networks in the East. Some of these networks were related to China, therefore, words of Chinese origins could also be found in the dictionary. One example is chin-chin,which the dictionary explains “In the “pigeon English” of Chinese ports this signifies ‘salutation, complements,’ or ‘to salute,’ and is much used by Englishmen as slang in such senses.”1 This usage has been shown in an earlier post (see 2. Chin-chin). Here, the featured postcard shows a Chinese procession described as “chin-chin joss”. The image depicts a group of Chinese carrying different offerings to the god or deity, called joss in Chinese Pidgin English. Joss is derived from the Portuguese word deus meaning ‘God’. Since the object of chin-chin is a deity, chin-chin means ‘worship’, and the phrase chin-chin joss refers to religious worship.

Samuel Wells Williams was a missionary, linguist, and sinologist from the United States. He arrived at Canton in 1833. He was the alleged author of an anonymously written article “Jargon spoken at Canton” published in The Chinese Repository (1836). The article gives a detailed description of how cross-cultural communication was achieved in Canton, and the “jargon” being discussed is Chinese Pidgin English, or Canton English as used in the article. Samples of Chinese Pidgin English are included to illustrate the characteristics of the language. A foreigner visits a shop in Canton (now Guangzhou) and finds some red sticks, so he asks the shopkeeper what they are. Below is their conversation.2

Foreigner: This have what thing?

Chinese: That hab joss-tick; China custom makee chin-chin joss.

Chinese Pidgin English originated in 18th-century Canton and its creation was a concerted effort of different ethnicities. Since the Westerners and Chinese did not share a common language, they devised a new language, now known as Chinese Pidgin English, to serve as a lingua franca. As Chinese Pidgin English is a product of languages in contact, we can see linguistic features from different languages, particularly Cantonese and English. Let’s look at some lexical and grammatical characteristics of the language. Hab is an orthographic variant of have. Though both are derived from English, have or hab in pidgin English functions differently from standard English. The two instances of have and hab in the pidgin function as a copula verb expressing ‘to be’ instead of ‘to have’. Note how the visitor asks the question. The question word what thing ‘what’ occurs at the end of the question instead of at the beginning of the sentence. Cantonese speakers would not find putting question words at the sentence’s final position unusual because this is the typical word order in Cantonese. Therefore, a translation of This have what thing? in Cantonese is 呢ni1啲di1係hai6乜mat1嘢je6, where 乜mat1嘢je6 means ‘what thing’. The thing that the foreigner is curious about is red incense sticks used for worshipping gods according to Chinese custom. Such sticks are called joss-sticks. Traditional Chinese society is polytheistic, chin-chin joss is an important event in Chinese culture. The Chinese worship many gods, goddesses, and deities to seek protection and blessings for different areas of life. In the kitchens of Chinese homes, you may find a plaque honouring the 灶zou3君 gwan1 ‘Hearth God’ or ‘Kitchen God’, who reports the conduct of the family to the celestial gods. The 土tou2地dei6 ‘Earth God’ is the guardian of a certain location such as a house, a shop, a building, or a village. One of the most beloved gods/goddesses in Chinese families is the 觀gun1音jam1 ‘goddess of mercy and compassion’, who hears the cries of people. Expressing filial piety and respect for the ancestors is also considered a duty in Chinese tradition. Ancestor veneration (祭zai3祖zou2 or 拜baai3祖zou2先sin1) is an expression of reverence to the ancestors so that the deceased will continue to protect the descendants. At different periods of the year, usually at the beginning of Spring (立lap6春ceon1), Spring Equinox (春ceon1分fan1), Autumn Equinox (秋cau1分fan1), Winter Solstice (冬dung1至zi3), or the Chinese New Year, family members will pay homage to the ancestors. People sweep the tombs of their ancestors and offer foods, joss paper, and flowers to the deceased in the Ching Ming Festival (清cing1明ming4節zik1) and Chung Yeung Festival (重cung4陽joeng4節zik3), both festivals are public holidays in Hong Kong.

Living descendants will prepare different types of offerings to ensure that the dead have sufficient means in the afterlife. Joss sticks (incense sticks) and joss paper (spirit money) are burnt. There is also a variety of food offerings such as tea, liquor, rice, cake, fruit, chicken, etc. Perhaps, the most important of these food offerings is the pig or suckling pig which is roasted whole. The 金gam1豬zyu1 ‘golden pig’, so called because of the crisp and golden brown skin after roasting, is placed on a red tray. When the ancestors have finished “enjoying” the food, the descendants can take their shares.

1. Yule, Henry and Arthur Coke Burnell. 1886. Hobson-Jobson Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms. London: John Murray.

2. Anonymous. 1836. “Jargon spoken at Canton”. The Chinese Repository, Vol. IV. Canton.