Shanghai entered the international stage after being designated as one of the treaty ports in the Treaty of Nanking (1842). The internationalization of Shanghai included people, business, food, fashion, architecture, transportation, entertainment, education, sports, communication, language, and so on. In the International Settlement, you could hear different tongues: English, French, Russian, German, Italian, Japanese, you name it. One language that is missing from the picture is the so-called 洋涇浜英語, or Chinese Pidgin English. While the national languages named earlier are still actively spoken, Chinese Pidgin English has exited the international stage. This does not diminish the significance of Chinese Pidgin English, which was spoken for over 200 hundred years, starting its humble beginning in Canton and moving northward to Shanghai.

Let’s start with the name 洋涇浜, usually romanized as Yang-king-pang (Putonghua: Yangjingbang), as you can see from the featured postcard above. A 浜 is a creek, and 洋涇浜 used to be a tributary of the Huangppu River (黄浦江), separating the British Concession and the French Concession. The author of Shanghai: A Handbook for Travellers and Residents, Rev. C.E. Darwent, describes the creek as follows:1

“Beyond the [Shanghai] Club are a few other hongs, and then the boundary of the old British Settlement, the Yang-king-pang Creek–not exactly a beautiful waterway, but so useful for Chinese traffic and the conveyance of garbage, that it has resisted all proposals to arch it over and make of it a broad road out into the country.

A bridge leads over the creek into the French Settlement.”

The postcard above gives us an idea of the bustle around the creek in the early 20th century. The problems of hygiene and smell have been pointed out by Darwent, so in 1915 the British and French Concessions agreed to fill in the creek and turn it into a road Avenue Edward VII, named after King Edward VII of the United Kingdom. The current name of the road is Yan’an Road East 延安東路.

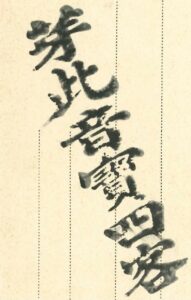

The French Concession occupied an area south of Yang-king-pang. After the First Opium War, European powers could enjoy not only free trade but also other types of autonomy such as establishing their postal services in China, for example, the stamp on the featured postcard was issued by the French. There were two types of French post offices in China. A type of post office was run by France and used stamps of France with the overprint CHINE ‘China’. These offices were set up in major treaty ports like Shanghai, Ningpo, Hankow, Tientsin, Chefoo, Peking, Amoy, and Foochow. The second type of French post offices were located in Hoi Hao (海口), Canton (廣州), Kouang-Tchéou-Wan (廣州灣), Mong-Tseu (蒙自), Pakhoi (北海), Tchongking (重慶), and Yunnanfu (昆明). These seven post offices were administered by French Indo-Chine and issued stamps with their own overprints, like the stamp on the postcard. While the front of the postcard is already very informative of the time, what is more interesting is the back of the postcard. Several Chinese characters, specifically 芽此音寶四客 appear on the back of the postcard. 芽 refers to the vegetable ‘sprout, shoot’; 此 means ‘this’ and 音means ‘sound, pronunciation’; and the last three characters 寶四客 seem to be the transcription of 芽 in French. If pronounced in the Shanghai dialect, 寶四客 would sound like po sy khah, probably representing pousse de pois in French. Using characters to transcribe words from foreign languages is a long-standing convention in China. This was also one of the ways that people learned Chinese Pidgin English.

Yang-king-pang was more than the name of a creek, it was also the name people adopted for a new variety of English spoken in Shanghai: Yang-king-pang English (洋涇浜英語). Although Yang-king-pang English is closely associated with Shanghai, the origin of this English variety must be dated back to the pre-treaty ports years in China. Canton 廣州 (now Guangzhou), situated in the south of China, was the only place where foreign traders could access business transactions with the Chinese. A problem emerged: how could the different ethnicities understand each other without a common language? Through trial and error, a new language appeared in the 18th century. People called the language by many names: Canton English, Pidgin/Pigeon English, “broken English”, “baby talk”, 番faan1話waa2, and so on, depending on how one looked at the language. For convenience, let’s use the name Chinese Pidgin English as the language is more widely known today. Although Chinese Pidgin English is a mixture of Cantonese and English, together with some peculiar features, it proves to be an effective medium for cross-cultural communication. As other treaty ports opened after the First Opium War, Chinese Pidgin English travelled north. In Shanghai, it was known as Yang-king-pang English (洋涇浜英語).

By the end of the 19th century, Shanghai was already a true cosmopolitan and was referred to as the “Paris of the Orient”. Its modernity attracted not only businesspeople but also tourists from all over the world. Like modern travellers, 19th- and 20th-century travellers often consulted travel guides in order to get what they needed. Rev. C.E. Darwent’s Shanghai: A Handbook for Travellers and Residents (1904) was an essential book for visitors. The handbook introduces the history, transports, services, and the must do/must see/must eat in Shanghai. Familiarity with the local language(s) would also be an advantage. Darwent explains the use of the lingua franca – Pidgin English as: “It is quite possible for the traveller to visit all the places and see all the sights mentioned in these pages without knowing a word of Chinese, but he will find that familiarity with pidgin-English will be of very great assistance.”

So, let’s look at a few examples from the book (Left: English; right: Pidgin).

Who is that (it)?

What is that?

Where is it?

What o’clock is it?

Why not?

Which is better, this or that?

How much is that?

What man?

What thing?

What side?

What time?

What fashion no can?

What piecee more good?

How muchee?

Instead of directly adopting the English question words, Chinese Pidgin English creates question words in a more transparent way – typically the word what is followed by the thing being questioned, for example, what time for ‘when’, what side or what placee for ‘where’, and what man for ‘who’. The meaning of can is very broad, including anything related to ability or possibility, for example, can do ‘That will do’ and the opposite is no can do. To ask yes/no questions, simply add a rising intonation to the end of declarative statements like this.

Will you be sure to do it?

Is the bargain settled?

Is that the lowest price?

Can secure?

Can puttee book?

No can cuttee?

With such travel guides, visitors could express themselves more easily and enjoy their trips more fully.

1. Darwent, Rev. C. E. 1904. Shanghai: A Handbook for Travellers and Residents. Kelly and Walsh, Limited: Shanghai.