The compradores were the right-hand men of the taipans, and the taipans were the heads of the companies. The featured image above is a poster of the film Tai-pan, adapted from James Clavell’s 1966 novel of the same title. The novel is set after the conclusion of the First Opium War (1839–1842). The Treaty of Nanking (1842) gave Europeans, especially the British, unprecedented rights to trade and settle in China. A new place name: Hong Kong began to be known in world history. The story of Tai-pan revolves around the competition between the heads (taipans) of two trading firms – Dirk Struan and Tyler Brock, both were employees of the East India Company before becoming independent traders. Dirk Struan is the tai-pan of Struan & Company.

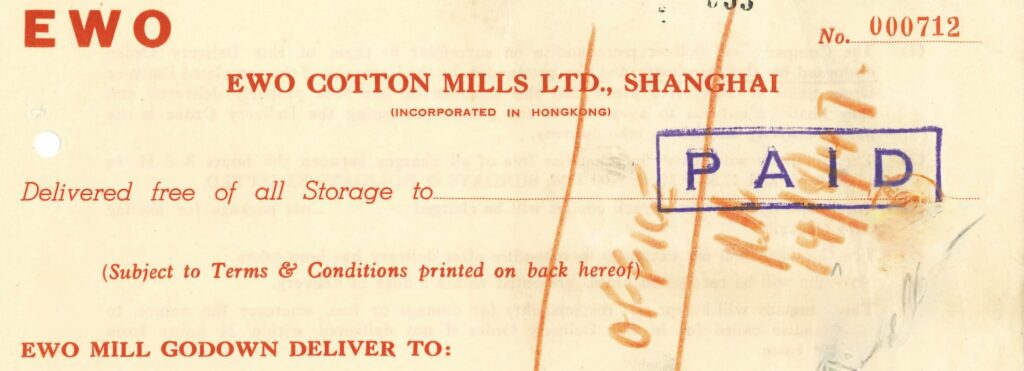

While the stories and characters of the novel and the film are fictional, the term taipan is well-documented in the Far East, particularly in China and Hong Kong. In Cantonese, it is called 大daai6班baan1, which literally means ‘big class’. Robert Morrison defines taipan as “The Chief of a Factory; the supracargo of a ship”.1 A supracargo (or supercargo) worked for a ship owner to manage the cargo on aboard a ship, including selling the cargo in ports and buying goods on the return journey. Before the signing of the Treaty of Nanking, foreigners could only set up their firms and dwellings within a designated area in Canton, the foreign traders and their employees worked in buildings called factories. Major European countries like Britain, Sweden, and France had established their factories. One of the most powerful taipans in the history of the China trade was William Jardine, head of the ‘Princely Hong’ Jardine, Matheson and Company. “Hong” (行hong2) was the term Chinese used to call a company or firm. William Jardine 威廉·渣甸 (1784 –1843), Scottish, graduated from the University of Edinburgh with a degree in medicine. In 1803, he joined the East India Company (EIC) and served as a surgeon’s mate aboard the Brunswick. He left the Company in 1817 and began his career as a trader. William Jardine’s career in China started with an invitation from Hollingworth Magniac to join Magniac & Co., then a major trading firm in Canton, China. Another Scotsman James Matheson (1796–1878) also joined the firm. The meeting of the two Scotsmen led to the founding of Jardine, Matheson and Company in 1832 in Canton and adopted the Chinese name 怡ji4和wo2 (Ewo), a wish for happiness and harmony for the future of their company. In the early days of the Canton trade, the businesses of Jardine Matheson mainly revolved around exporting tea from China to Europe and importing opium from India to China.The end of the trade monopoly of the East India Company in China in 1834 meant traders from any nation could start their businesses with Chinese merchants. Jardine and Matheson of course would not miss this golden opportunity. The end of EIC in Canton was captured by William C. Hunter, an American trader and partner of Russell and Company, who notes:2

“Few now remain who witnessed the final breaking-up and departure of ‘the Factory’ from Canton; personally, there was much regret, as it had always been a marked feature in the community. The ‘Outside’ Merchants, unshackled from licenses, hailed it as an auspicious day, opening up to them vision of prosperity, which soon assumed the form and substance of reality. As an event to be placed ‘on record,’ as the Chinese say, the first ‘free ship’ with ‘free teas’ was loaded at Whampoa and despatched for London on March 22, 1834, by the still existing house of Messrs. Jardine, Matheson, & Co. The vessel was named the ‘Sarah,’ Captain Whiteside.”

Though coming from different cultures, the taipans and the compradores were two important people in the company. They had to communicate effectively in order to ensure profits and maintain the daily running of the company. Not every compradore could speak English fluently like Tong King-sing 唐景星, so exchanges between the taipans and the compradores were conducted in Chinese Pidgin English, a lingua franca used to solve the language barrier. An example of such exchange is shown in Carl Crow’s Foreign Devils in the Flowery Kingdom. Carl Crow was a long-time resident of Shanghai. In this reconstructed dialogue between a Chinese compradore and a taipan, the taipan asks the compradore why the cargo is still in the warehouse even though there is already security paper. The compradore explains that the purchaser Kong Tai had run away from the creditors.3

Taipan: How fashion that chow-chow cargo he just now stop godown inside?

Compradore: Lat cargo he no can walkee just now. Lat man Kong Tai he no got ploper sclew [security].

Taipan: How come you talkie sclew no paper? My have go sclew paper safe inside.

Compradore: Aiyah! Lat sclew paper he no can do. Lat sclew man he have go Ningpo more far.

The interaction may sound hilarious according to modern standards; however, such exchanges were common and considered adequate back then. Some explanations of Chinese Pidgin English may help readers understand the interaction. Sound substitutions occur when certain English sounds are difficult for the Chinese to pronounce. For example, the ‘th’ sound would be replaced by ‘l’, ‘d’, or ‘t’ as in lat (that). Since the ‘r’ sound is also problematic for many Chinese, the ‘l’ would be the preferred substitution, as in ploper (proper). However, note that sclew is not screw but security. The meanings of chow-chow ‘eat, food, mixed’ vary depending on the context. The meaning here is ‘mixed, assorted’ cargo. The exclamation Aiyah comes from Cantonese 哎aai1吔jaa3, expressing a range of emotions like surprise, disappointment, excitement, etc. As many traders travelled back and forth between India and China, a few Hindi words are found in Chinese Pidgin English, one example from the dialogue is godown (warehouse). English third person pronouns are reduced to one form he, so that Kong Tai, chow-chow cargo, and sclew paper are all referred to as he. My is also used as a subject pronoun.

Since Hong Kong island was ceded to Britain after the First Opium War, many companies moved to or established branches in the newly established colony because of the good harbour and more Western lifestyle. Jardine Matheson set foot in East Point of Hong Kong (present-day Causeway Bay) and built a stone godown there in 1841. Even now we can still find various places in Causeway Bay bearing a connection with the company: Yee Wo Street (怡ji4和wo2街gaai1), Matheson Street (勿mat6地dei6臣san4街gaai1), The Jardine Noonday Gun (怡ji4和wo2午ng5炮paau3), Jardine’s Bazaar (渣zaa1甸din1街gaai1), Jardine’s Cresent (渣zaa1甸din1坊fong1), and Jardine’s Lookout (渣zaa1甸din1山saan1). In 1844, Jardine Matheson established an office in Shanghai. They were the first foreign company to build cotton mills there. The Ewo Cotton Spinning and Weaving Company was opened in 1897 (Tales of Old Shanghai). Investments in diverse industries made Jardine Matheson the largest foreign trading firm in the Far East by the end of the 19th century.

1. Morrison, Robert. 1828. Vocabulary of the Canton Dialect vol. 2. Macao: The Honorable East India Company’s Press by G.J.

2. Hunter, William C. 1882. The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days 1825–1844. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co.

3. Crow, Carl. 2011. Foreign Devils in the Flowery Kingdom. Hong Kong: Earnshaw Books, Ltd.