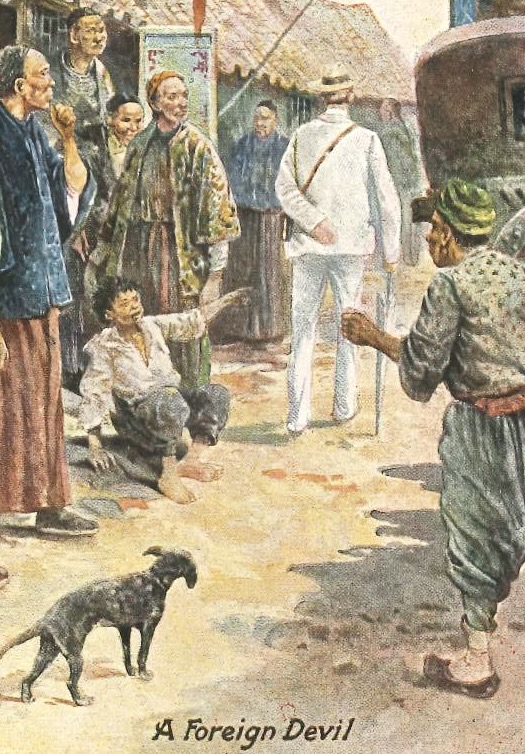

The foreignness of people and things often results in curiosity, suspicion, and hostility. Such feelings are sometimes reflected in language as people may create terms to call certain groups of people. Hong Kong is no exception. Cantonese also has terms to call specific ethnicities, for example, 「阿aa3差caa1」and 「摩mo1羅lo1差caa1」refer to the South Asians;「㗎gaa4仔zai2」and「㗎gaa4妹mui1」 are the Japanese. These terms are now obsolete. However, some terms referring to white Westerners are still commonly seen and heard. These terms are 「鬼gwai2佬lou2」, literally ‘ghost man’ and is usually romanized as gweilo, 「鬼gwai2婆po2」 ‘ghost woman’,「鬼gwai2仔zai2」 ‘ghost boy’, and「鬼gwaai2妹mui1」, ‘ghost girl’. The second characters of these names differentiate gender and age, but all names are introduced by the character 鬼gwai2, whose literal meaning is ‘ghost, evil, devil.’ Today, these colloquial names are generally not considered derogatory, they are even used among white people as in Martin Booth’s book Gweilo: Memoirs of a Hong Kong Childhood and Christine Cappio’s Gweimui’s Hong Kong Story.

Creating informal names for foreigners is not a current practice, back in the 18th and 19th centuries the Chinese called the Europeans “foreign devils”, the English equivalent of the Chinese term 番faan1鬼gwai2. The character 番faan1 is applied to things of foreign origins, for example, 番薯(or 蕃薯) ‘sweet potato’ and 番faan1話waa2 ‘foreign language’ as in 紅hung4毛mou4通tung1用jung6番faan1話waa1 (A common language used with the red-haired people). Spellings like fan kwae, fan qui, etc were adopted in English-language sources, for example, in William C. Hunter’s book The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days 1825-1844. Since Canton was the only port permitting foreign trade, activities of Europeans would centre in Canton or Portuguese-ruled Macau. William C. Hunter was an American trader and a long-time resident of Canton. In his memoir, he explains the different types of fan kwaes staying in Canton (p. 28).1

“Although by the Chinese all foreigners were called ‘Fan Kwaes,’ or ‘Foreign Devils,’ still a distinction of the drollest and most characteristic kind was made between them. The English become ‘Red-haired devils’; the Parsees, from the custom of shaving their heads, were ‘White-head devils’; Moormen were simply ‘mo-lo devils’. The Dutch became ‘Ho-lan,’ the French ‘Facian-sy,’ and the Americans ‘Flower-flag devils.’ The Swedes were ‘Suy’ and the Danes ‘Yellow-flag devils.’ The Portuguese have never ceased to be ‘Se-yang kwae,’ thus retaining the names first applied to them on their arrival from the ‘Western Ocean’ (which the words signify), while their descendants, natives of Macao, are ‘Omum kwae,’ or ‘Macao devils’ from the Chinese name of the town.”

We can already appreciate the diversity of people and cultures from this short description. Some remarks on the origins of these names may be helpful here. The English are the 紅hung4毛mou4鬼gwai2 ‘red-haired devils’. The Parsees who come mainly from Bombay (now Mumbai), are the 白baak6頭tou4鬼gwai2 because they wrap their heads with white cloth. The Moors or 摩mo1羅lo1鬼gwai2 according to the Chinese, is a rather complex concept and does not refer to a single ethnic group. Moors could refer to Muslims of North Africa, African descent in Europe, and people with dark skin. The Dutch are called the 荷ho4蘭laan1, derived from Holland. As to the French, the term ‘Facian-sy’ could be 法faat3蘭laan1西sai1. America used to be called 花faa1旗kei4. The name for the Americans, 花faa1旗kei4鬼gwai2, comes from the flowery design of the American flag. Today, we can still see this older name being used in 花faa1旗kei4銀ngaan4行hong4 Citibank National Association and 花faa1旗kei4蔘sam1 ‘American ginseng’. 瑞seoi6 is short for 瑞seoi6士si6 ‘Sweden, Swdish’. The Danes are the 黃wong4旗kei4鬼gwai2 because of the colour of their flag. The Portuguese, the first Europeans to arrive in China, are the 西sai1洋joeng4鬼gwai2 because, as Hunter explains, they came from 西sai1洋joeng4 ‘Western Ocean’. However, during the Ming and Qing dynasties of China, the Portuguese are also known as 佛fat6朗long6機gei1, deriving from the Arabic word Faranji. The Portuguese were permitted to settle in Macau in 1557. The 澳ou3門mun2鬼gwai2 are people of mixed ancestries, usually Portuguese fathers and Asian mothers. Whether historical or current, the reference to foreigners as 鬼gwai2 shows a sense of alienation. Today advances in technology and communication allow us to understand other cultures more easily, so the application of the word 鬼gwai2 is probably more a result of habit instead of hostility. However, in the olden days, otherness could easily lead to distrust, separation, and even antagonism. In the early days of China-West exchanges, activities and movement of foreigners were strictly regulated and confined to the Factory area where the Europeans set up their business houses and dwellings. Foreign settlers were aware of the resentment of the Chinese.

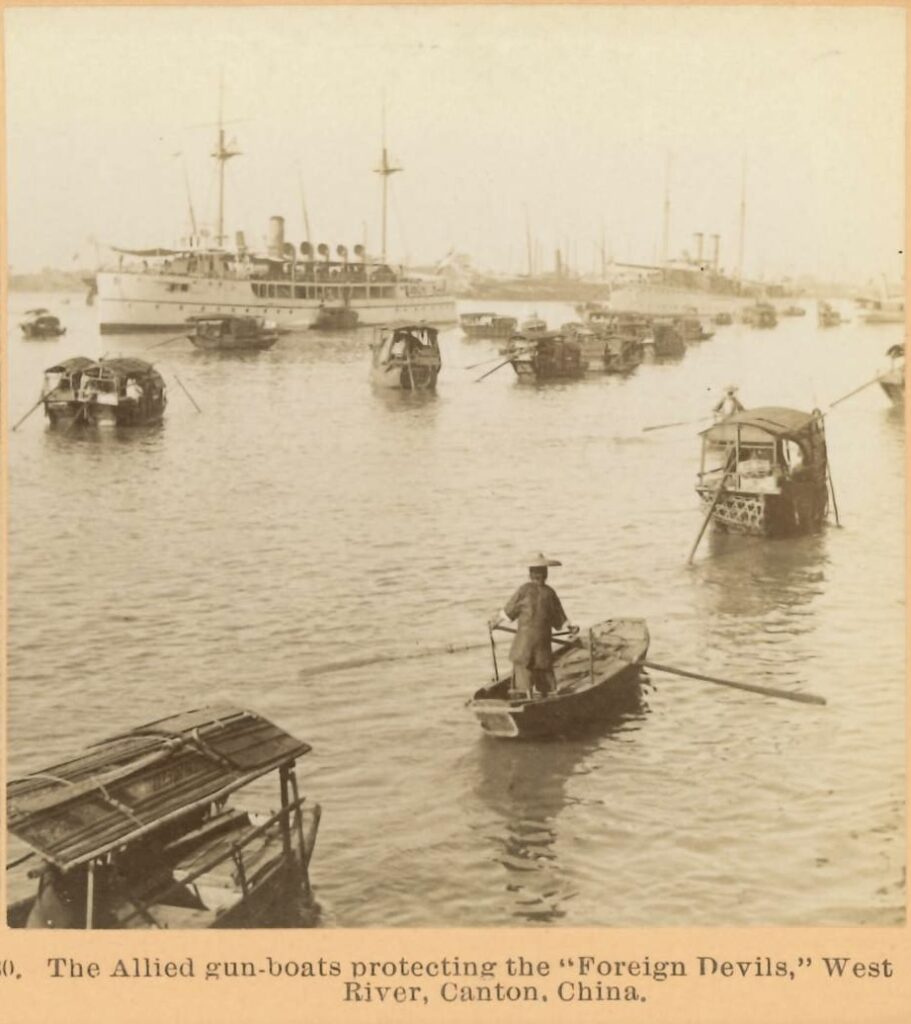

After the defeat in the two Opium Wars, China was forced to open up the market to foreign trade. Consequently, more treaty ports including Canton and Shanghai were opened, creating a period of intense East-West contact never seen before. As foreigners invested heavier and heavier in China and occupied more and more Chinese territories, they found it necessary to protect their lives and properties. The situation could be illustrated in the photograph above captioned “The allied gun-boats protecting the “foreign devils,” West River, Canton.” The West River 西sai1江gong1 (or Si Kiang) is the longest river in southern China. The upper course of the river is in the Yunnan province. It runs eastward and ends at the Pearl River Delta, Guangdong province, where Canton is located. Armed with small cannons and machine guns, these gunboats were purpose-built for river navigation. In northern China, the Yangtze Patrol was formed by the United States Navy to protect American citizens and properties along the Yangtze River. Other European nations and Japan also possessed gunboats to safeguard their interests and extraterritoriality in China.

1. Hunter, William C. 1882. The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days 1825-1844. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co.