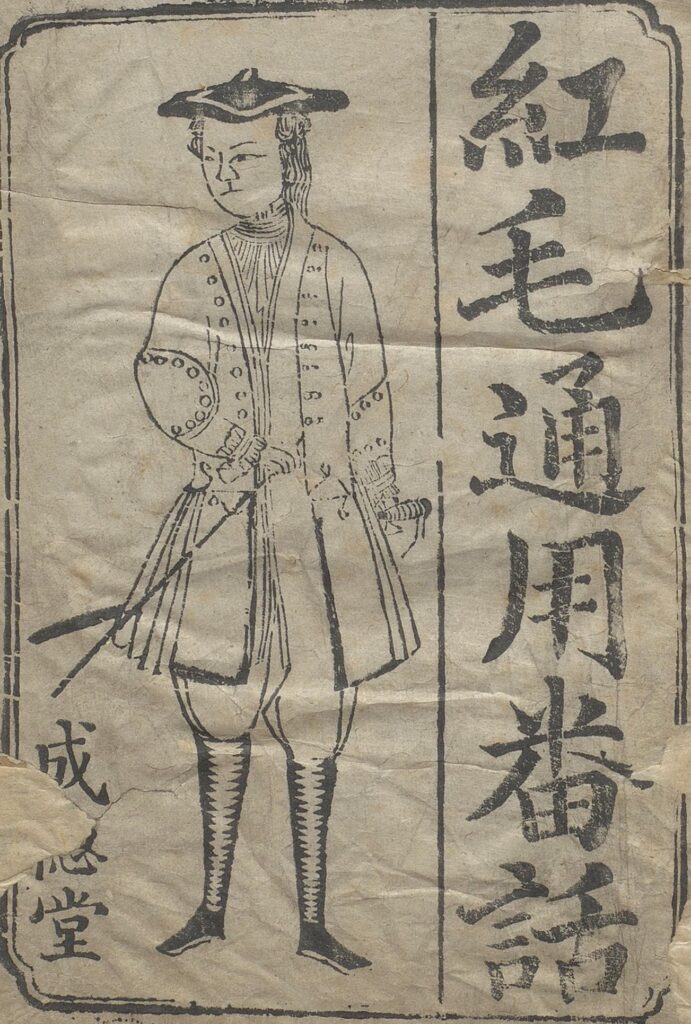

To the Hokkien-speaking Chinese, the term 紅hung4毛mou4 is familiar as it is traditionally used to refer to the Dutch and later Europeans. Hokkien (福fuk1建gin6話waa2) is spoken mainly in the Fujian (福fuk1建gin6) province of the south of China. As the province faces the South China Sea, Hokkien people are skilled seafarers and are significant diaspora groups in Taiwan, Singapore, and the Philippines. The Portuguese were not only the first Europeans to arrive in China but also the first to gain rights of settlement in Macau in 1557. Other Europeans would not let the Portuguese get the lion’s share. The Dutch, for example, were in a constant rivalry with the Portuguese. In 1622, the Dutch attempted to invade Macau but the 3-day attack ended with the Portuguese’s victory. In 1624, the Dutch successfully occupied southern Formosa (now Taiwan) and used it as a base to trade with China and Japan. Spain remained to be in control of Northern Formosa . The featured postcard above shows the historical site Fort San Domingo located at Tamsui in northern Taiwan. Built by the Spanish in 1628, the fort was dismantled by the Spanish when the Dutch ousted the Spanish in 1642. The Dutch built another fort at the original site naming it Fort Antonio. The Chinese called the fort 紅毛城, meaning ‘red-haired fort’ (Âng-mn̂g-siânn in Hokkien). So who were the 紅毛 ‘red-haired’? William C. Hunter, an old China hand, explained the term in his book The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days 1825-1844 (pp. 16-17): “tradition said the Dutch had red hair, which led the Chinese facetiously to apply the terms ‘Red-headed Devils’ ever after to all foreigners alike.”1

A common problem encountered in multiethnic communication is the language barrier. One example is the plantation situation in Hawai‘i, where contract labourers speaking different native languages were confined in the same environment and lacked a common language. New languages such as Pidgin Hawaiian, Hawai‘i Pidgin English, and Hawai‘i Creole English evolved as ways to solve the communication barrier. Another situation can be found in Canton 廣gwong2州zau1 (now Guangzhou), where international trade was the reason for the emergence of a new language.

Lucrative profits obtained from trading tea, silk, porcelain, and other highly demanded commodities attracted many Europeans to visit Canton annually in order to make business deals. Canton, the only port allowing foreign trade before 1842, became a hub for international trading centre. This gathering of different ethnicities in Canton created a situation where a lingua franca or a common language was needed to enable cross-cultural communication. The lingua franca that emerged in the 18th century under this circumstance was a language now known as Chinese Pidgin English. Chinese Pidgin English is not only a new language, it also differs from traditional languages like Cantonese and English in some ways. The vocabulary and grammar of Chinese Pidgin English are contributed by multiple sources. While English is the main source of words, other languages like those below also make up the vocabulary of the pidgin.

Portuguese: compradore (from comprador ‘buyer’), joss (from deus ‘god’), sabe/savvy (from saber ‘know’)

Malay: picul, candareen, catty, tael (these are units of weight)

Hindi: chop, shroff

Cantonese: chin-chin, chop-chop, sampan, taipan

Hokkien: cumshaw (from 感kám謝siā meaning ‘thankful’)

Although some people viewed Chinese Pidgin English negatively, using expressions like “baby talk” and “corrupted” English, the language was an indispensable part of foreign trade at the time. The word “pidgin” is believed to be a pronunciation of the word business by the Chinese. Therefore, Chinese Pidgin English is essentially a business language used among traders of different linguistic backgrounds.

Like all languages, the grammar and use of Chinese Pidgin English evolved as social conditions changed. The 19th century was the heyday of Chinese Pidgin English as an increasing number of foreigners and their families were allowed to settle in Canton and other port cities in China, interactions between the Chinese and the foreigners became more and more frequent and diverse. In other words, Chinese Pidgin English grew from a business language to a medium employed by different ethnicities whenever cross-cultural interactions arose, for example, between western employers and Chinese domestic servants. The convenience and advantages of knowing Chinese Pidgin English were probably the reason for the popularity of Chinese Pidgin English phrasebooks like 紅hung4毛mou4通tung1用jung6番faan1話waa1 (A common language used with the red-haired people). The American missionary and sinologist Samuel Wells Williams, who was the alleged author of the article “Jargon spoken at Canton” writes:

“We have before us a manuscript book, in which the English sounds of things are written in Chinese characters, underneath the name of the article also in Chinese. Similar books are very common among the people in Canton, and it is deemed one of the first steps to the acquisition of English, to copy out one of these manuscripts.”

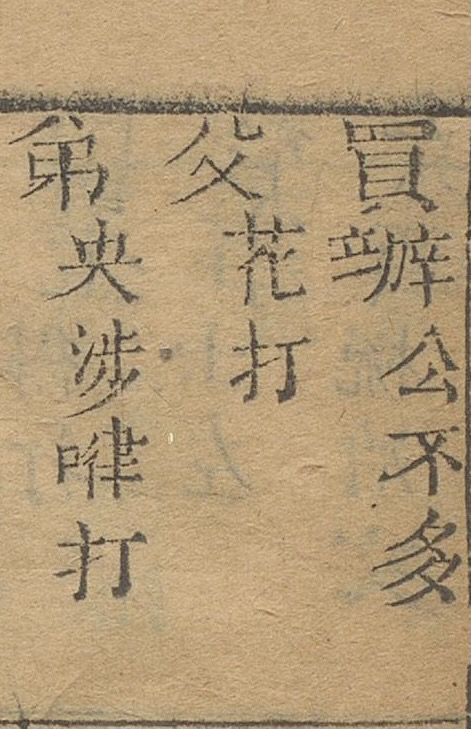

To illustrate how the transcription system works, some entries from the phrasebook are shown on the right. The Chinese meaning 買辦 (compradore) is given first and is followed by a transcription in Chinese characters 公不多. Since the phrasebook was published in Cantonese, the characters are pronounced in Cantonese, thus 公gung1不bat1多do1. This seems to be the most convenient way to let Chinese readers quickly learn the English words at the time, and it worked quite well.

1. Hunter, William C. 1882. The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days 1825–1844. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co.

2. Anonymous. 1836. “Jargon spoken at Canton”. The Chinese Repository, Vol. IV. Canton.