Previously, we saw a postcard posted from Honolulu to Hong Kong dated 1888 (see 3. Chin-chin). As shown below, the beginning of the message was a usual note to tell the recipient of the sender’s safe passage. What is more informative is the return journey to Hong Kong.

“According to promise I pen you a few lines to let you know of our safe arrival in port, after a tedious passage of 53 days; the vessel leaves here in 3 or 4 days hence, bound back to “Hongkong” with Chinese passengers.”

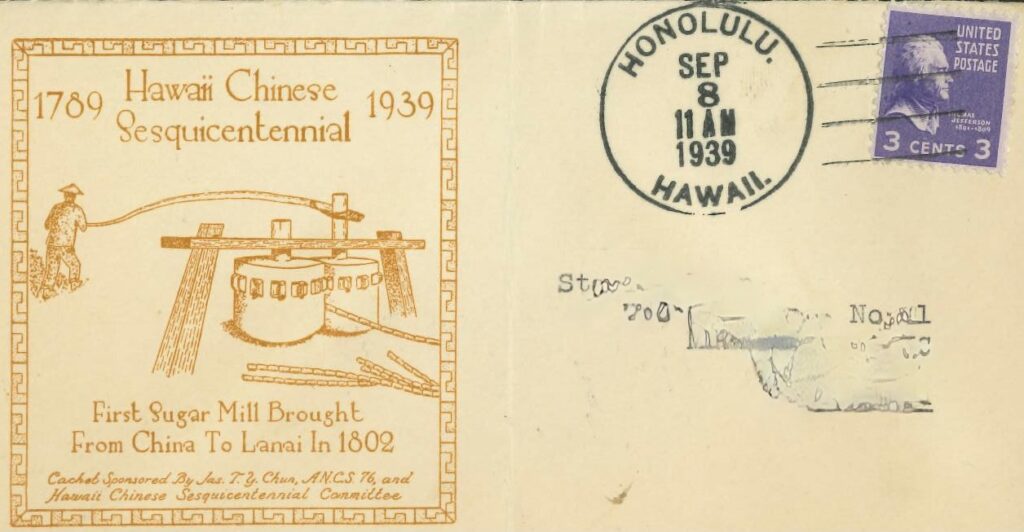

The historical connection between China and Hawaiʻi dates far earlier that the postcard’s mailing date (1888) shown in the previous article (see 3. Chin-chin). As we can see from the featured image of this article, the arrival of Chinese in Hawaiʻi can be traced to at least the last decade of the 18th century. In other words, Chinese-Hawaiʻi interaction has lasted more than two hundred years. As shown in the featured image, the official record of Chinese in Hawai‘i can be dated as late as 1789. Moreover, the picture suggests that the type of work that the early Chinese engaged in was related to sugar production. It is believed that a Chinese called Wong Tze-Chun brought a mill and boilers to Lāna‘i and established the first sugar production in 1802. However, historical records on Wong are scarce.

While in 1888, the journey from Hong Kong to Honolulu took 53 days, we can imagine how lengthy and difficult the journey would be one hundred years earlier. Over the past 200 years, Chinese people have become an important part of the history of Hawaiʻi. As contract labourers, most Chinese settled in Honolulu, which the Chinese called 檀taan4香hoeng1山saan1 (pronunciation in Cantonese). The Chinese name means ‘sandalwood mountains’, apparently indicating what it was famous for. American merchants began to trade in sandalwood (‘iliahi) between Hawaiʻi and China around the last decade of the 18th century. Sandalwood was in high demand in Canton, China because the wood is not only fragrant but also has medicinal functions. The sandalwood trade peaked between the 1810s and 1820s but by the 1830s supplies of sandalwood became exhausted due to deforestation.

The plantation system in Hawaiʻi began in 1835, and Most Chinese contract laborers were mainly from the Guangdong province of southern China speaking Cantonese and Hakka. Between the 1850s and 1870s, the number of Chinese reaching Hawai‘i ranged from several hundred to several thousand. By the end of the 19th century, there were nearly 22,000 Chinese in Hawaiʻi. Initially, the Chinese labourers worked in the plantation fields, but after completing their contracts some moved to urban districts and became shopkeepers, farmers, and entrepreneurs. Besides the Chinese, plantation workers came from other ethnicities such as Portuguese, Japanese, Filipinos, Korean, and Puerto Ricans. Diseases introduced by the arrival of foreigners, the harsh work conditions in the fields, and the continuous influx of foreign labourers brought drastic changes to the demography of Hawaiʻi. While within a century the population of Hawaiians dropped from 71,019 in 1853 to 21,796 in 1934, there was a significant surge in the non-Hawaiian population, for example, the number of Chinese increased from 364 in 1853 to 26,989 in 1934.1

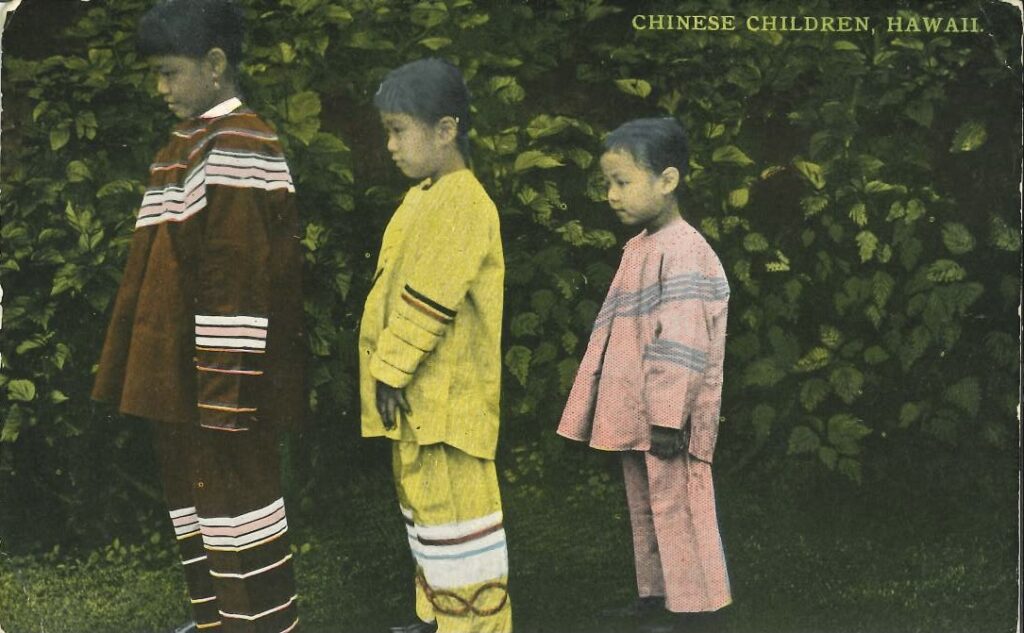

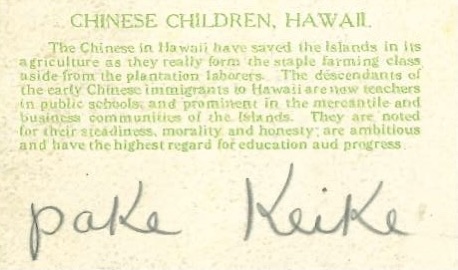

In Hawai‘i, the white people are called haole and the Chinese are called pākē. The word “pake keiki” on the back of the featured postcard means ‘Chinese children’. The postcard tells the visitors that “The descendants of the early Chinese immigrants to Hawaii are new teachers in public schools and prominent in the mercantile and business communities of the Islands. They are noted for their steadiness, morality and honesty; are ambitious and have the highest regard for education and progress.” An example that fits this description is a Chinese called William Kwai Fong Yap, who had a great impact on education in Hawai‘i. Mr. Yap was born in Honolulu in 1873 and married his wife in Hong Kong in 1893. Originally working at the Bank of Hawaii, Mr. Yap later used most of his time for different educational projects. One of the projects was the proposal to expand the College of Hawai‘i into a university so that young people in Hawai‘i could pursue professional careers. In 1919, the college was renamed the University of Hawaiʻi and Mr. Yap was one of the men behind this change. He died in Honolulu in 1935.2

1. Reinecke, John E. (1969). Language and Dialect in Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

2. “William Kwai Fong YAP, age 61, of Honolulu, Dies 25 FEB 1935. Active Here As Educator” The Honolulu Advertiser, 26 Feb 1935, Tue., Page 2: https://www.newspapers.com/clip/11709425/william-kwai-fong-yap-age-61-of/