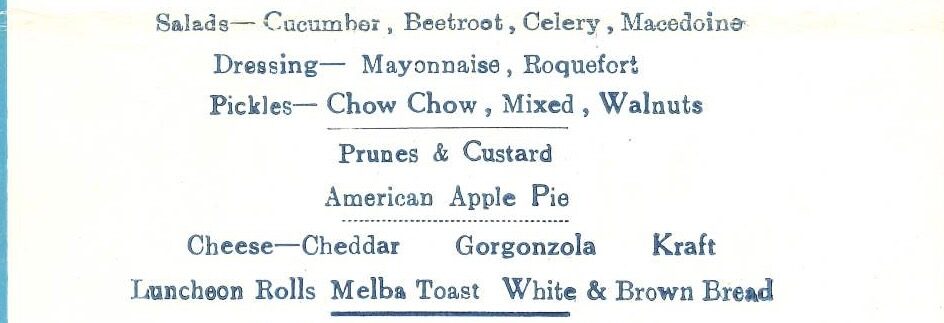

By the late 19th century, cruising had become a popular vacation choice. Shipping companies that used to rely on cargo shipment shifted to or invested more in building passenger ships instead. Famous cruise liners included White Star Line, Cunard Line, White Star Line, Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O), Australian-Oriental Line, Dollar Steamship Line, Pacific Mail Steamship Company, and many more. In 1949, SS Changte, owned by the Australian-Oriental Line, visited Hong Kong. Established in 1912, the Australian-Oriental Line operated voyages between Sydney and Hong Kong. The life of SS Changte was closely related to Hong Kong. The ship was built by the Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock Company in 1925 and was scrapped in Hong Kong in August 1961, the same year the company closed. On cruises, the travel experience not only includes entertainment, culinary delight is also an essential part. To give passengers a memorable voyage, liners offered a wide variety of dishes as you can see from the luncheon menu of SS Changte. There was a food item called chow chow in the featured menu above. In the US, chow chow is mainly a southern thing. It is a condiment or relish of preserved vegetables with vinegar and sugar, served cold as a relish or eaten by itself. Recipes of chow chow vary from family to family and region to region but the common ingredients include cabbages, onions, peppers, tomatoes, and spices. The origins of the condiment as well as its nameare still a puzzle. Popular suggestions include that it was brought to America by the Arcadians of Nova Scotia, Canada. Hence, chow could be derived from French chou for cabbage. John F. Mariani, on the other hand, suggests a Chinese origin and states, “The word may be from Mandarin Chinese cha, “mixed,” and dates from the 1840s, when Chinese laborers worked on the railroads of the American West.”1 However, as the vast majority of Chinese immigrants in America in the 19th century originated from Guangdong province, where Cantonese is the primary language, a Chinese etymon of chow would more likely be Cantonese instead of Mandarin.

Another reason that makes the name chow chow interesting is that the same form was used in a language that we now call Chinese Pidgin English, spoken in Canton two hundred years ago. Canton, a historical name for Guangzhou of the Guangdong province, was the only place in China where international trade took place. As to why Chinese Pidgin English emerged, we will look into the historical and linguistic contexts later. For now, let us take it for granted that Chinese Pidgin English was a lingua franca between the Chinese and the Westerners and look at the uses of chow chow in the pidgin. The British interpreter John Robert Morrison (1814–1843) notes three uses of chow-chow, namely “mixed, miscellaneous…food…to eat food.”2

An American trader and a long-time resident of Canton in the 19th century, William C. Hunter gives some examples of chow-chow in his book The Fan Kwae at Canton. A chow-chow cargo contains an assortment of goods; a chow-chow shop sells provisions of all kinds; and one of the factories (i.e., commercial establishments and dwellings of Europeans) is called Chow-chow because its inhabitants are from a variety of people like the Parsees, Moormen, and people from India.3

As a lingua franca, Chinese Pidgin English allows the Chinese and Westerners to have a common means to communicate, as shown in the following dialogue which not only gives us a taste of the language but also illustrates the use of chow-chow for food and eating. The conversation is between a European employer and his Chinese “boy” (i.e., a male servant) who requests a leave of absence in order to go god-worshipping (chin-chin Joss) during the Chinese New Year.4

Employer: Which piecee Joss you go chin-chin?

Boy: Dono, belong have got one piecee flend, my go along he; suppose place he go what side?

It is customary to visit the temple and pay respect to the gods and deities (Joss) during the Chinese New Year. That’s why the boy asks for absence so he can chin-chin ‘worship, pray’ the joss with his friend. Joss is derived from the Portuguese deus for god, while chin-chin is from the Chinese 請 ‘invite, please.’ The boy’s request was granted on the condition that other servants must stay at home.

Employer: Well, go on then; but mind, all the boys can’t go.

Boy: Oh no, some piecee makee stop here.

Employer: But don’t they want to go and chin-chin Joss?

Boy: By-and-by can do, next year he go, my makee stop, so fashion.

The employer is curious about what people do on that day.

Employer: What do you do when you go to see Joss?

Boy: What thing my do? Chin-chin he, pay he kumshaw (present), pay that priestee man litty cash; he makee pray all the same my, by-and-by my go catchee chow chow long one piecee flend.

Like many Chinese, the boy prays to the god and offers him some presents. A small sum of money will be given to the temple staff and they will pray on behalf of the boy. After worshipping, the boy will go eating with his friend. Kumshaw is another word of Chinese origin. It is derived from 感謝 ‘gratitude’ in Hokkien, spoken in the Fujian province, but in Chinese Pidgin English kumshaw refers to present or tip. Chow-chow is also suggested to be from Chinese but its exact etymon is still debatable. You may wonder what piecee (from English piece)does in phrases like which piecee Joss, one piecee flend, and some piecee. While in English the use of piece in these phrases is unnecessary, the structure of such phrases corresponds to the grammar of Cantonese. Cantonese uses a wide variety of classifiers before nouns of different types. Although Chinese Pidgin English reduces all the Cantonese classifiers to piecee only, its functional and structural properties are similar to Cantonese.

In order to understand the circumstances that gave rise to Chinese Pidgin English, a brief explanation of the historical context is necessary. The current name Chinese Pidgin English partly indicates the main contributors of the language: Chinese, specifically Cantonese and English. But as in the dialogue above other languages like Portuguese and Hokkien should not be overlooked. The word pidgin is a representation of English business. So, Chinese Pidgin English acted as a lingua franca to allow speakers of different native languages to conduct business. Portuguese explorers and traders were the first Europeans to reach China in the 16th century. Possessing a settlement in Macau, the Portuguese and their descendants of mixed Portuguese and Asian ancestries took advantage of being the intermediaries between the Chinese merchants and Western traders. In fact, knowledge of Portuguese or some form of it was deemed essential for cross-cultural interactions. However, as more and more Europeans entered China, particularly the British, Portuguese dominance in China began to wobble. Regular commercial relationships between Britain and China began in the late 17th century when the East India Company formally established trade relationships with China. Trade in opium in the 18th century further consolidated British economic and political influence in China. Chinese Pidgin English also emerged during this period. In order to regulate the activities of the Westerners, the Chinese government designated a piece of land southwest of Canton and facing the Pearl River as the foreigners’ business area and dwellings. It was in this multicultural and multilingual area that Chinese and Westerners co-constructed a language referred to by different names – Canton jargon, Canton English, broken/corrupted/pidgin English, baby talk, etc. The pidgin was so effective that it was adapted into Shanghai and Hong Kong after the First and Second Opium Wars when China was forced to open up for foreign trade. The pidgin was no longer a business language, it was employed whenever cross-cultural communication arose, as in the household. Hong Kong was the last place where Chinese Pidgin English was spoken but it was effectively extinct around the 1960s/70s.

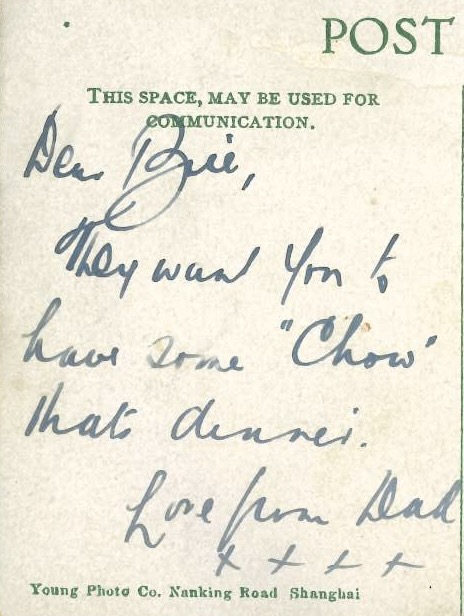

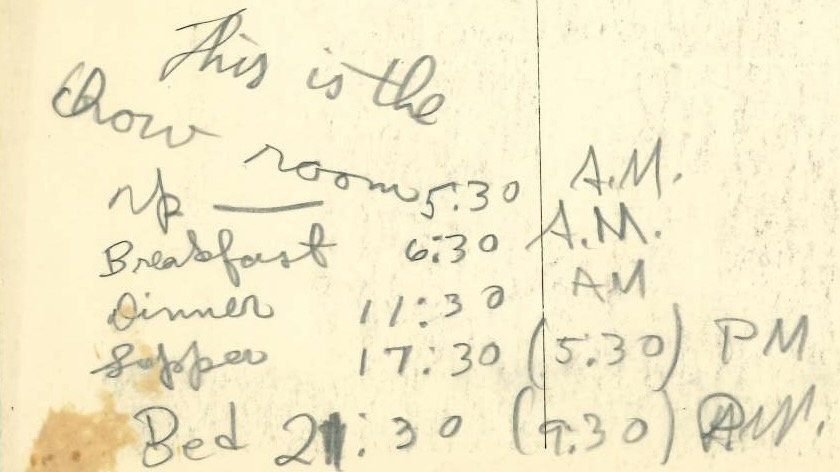

On the left hand side is a message on the back of a postcard of the 20th century. A “chow room” was like a canteen. The message contains the sender’s the daily schedule and meal times. The other side of the postcard shows a picture of trainees at the naval training station in Newport, Rhode Island. While following the norm of having three meals a day, some people may find the terminology a bit confusing. This is because “dinner” should be “lunch” and “supper” is normally called “dinner” now.

The confusion is due to the differences in the number of and times at which meals are taken across time and space. During the Middle Ages, people usually took their first and largest meal around midday. This meal was called dinner. It should be noted that eating in the morning was associated with the lower class because only farmers or workers needed food for energy to do their work. To some, dinner and supper are semantically interchangeable today but historically they are different. People also went to bed early in the Middle Ages and took a light, evening meal called supper. Breakfast did not become a common meal until the 16th century. The advent of industrialization drastically changed people’s daily schedules. People began to live in cities and work in factories; electricity extended work hours and as a result, people ate more. Breakfast became an essential first meal and “dinner” began to be taken between midday and evening and began to be called “lunch.” After finishing a day’s work, people took “dinner,” now the biggest meal, in the evening.5 In some parts of the UK and US, older generations may still use “dinner” and “supper” to denote the midday and evening meals respectively. Adding to the complexity is that in some parts of the UK, people call the evening meal “tea,” not the beverage.6

1. Mariani, John F. 1983. The Dictionary of American Food and Drink. New York: Ticknor & Fields.

2. Morrison, John Robert. 1834. A Chinese Commercial Guide, Consisting of a Collection of Details Respecting Foreign Trade in China. Canton: Albion Press.

3. Hunter, C. Willaim. 1882. The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days 1825–1844. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co.

4. Anonymous. 1860. The Englishman in China. London: Saunders, Otley & Co.

5. Merriam-Webster: https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/dinner-vs-supper-difference-history-meaning

6. Our Dialects: https://www.ourdialects.uk/maps/meal/