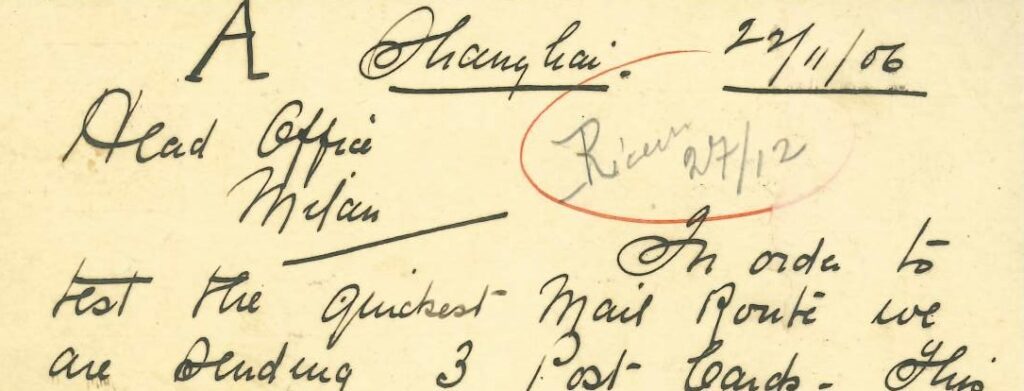

One of the periods that had long lasting global impact was the Industrial Revolution, occurring between the 18th and early 20th century spearheaded by Britain and spread to Europe and America. The Industrial Revolution brought changes at individual, societal, and global levels that contrasted sharply with the past. These changes included rapid economic growth, groundbreaking ideas, mass iron and steel production, diverse manufacturing industries, a surge in population, improved living conditions, widespread education, and so on. A notable notion permeating different areas was “speed”, particularly in communications and transportation. As lives and societies became increasingly competitive, a crucial factor for winning was speed. The featured postcard above aptly illustrated the importance of time. The complete message was: “In order to test the quickest Mail Route we are sending 3 Post Cards. This one A by the French Mail, which leaves early tomorrow 23/11/06. B will leave by the Empress Boat leaving 24/25 & C by the English Mail leaving 26/27. Please report the arrivals.” It was sent from Shanghai to the Societa Commissionaria d’Esportazione in Milan, Italy. The mission was simple – to find out which vessel took the least time to reach the destination. The result of the race remains unknown as cards B and C are still to be located. But this card (A), which was received on 27/12/1906, told us that the journey took a little more than one month.

Apart from carrying freight, ships were also a major channel for communication. The modern postal system can be traced back to the beginning of international commerce in the Mediterranean. There was a high demand for fast and reliable exchange of information between merchants and traders whose businesses were closely related to changes in the socio-political situations. Maintaining constant contact with customers and business partners also increased business correspondence. European empire expansion during the Age of Discovery increased intercontinental mails and dispatches significantly. These reasons hastened the development of systematic and reliable postal services. In the 15th century, Europe experienced another revolution – the invention of the first printing press by Johannes Gutenberg. The invention not only popularized commercial printing but also indirectly stimulated letter writing. In 1869, Austria introduced a new, inexpensive form of communication: the postcard, which brought another wave of increase in mailing. The change and expansion of mail from official to commercial and private correspondence made postal services a part of people’s daily lives.1

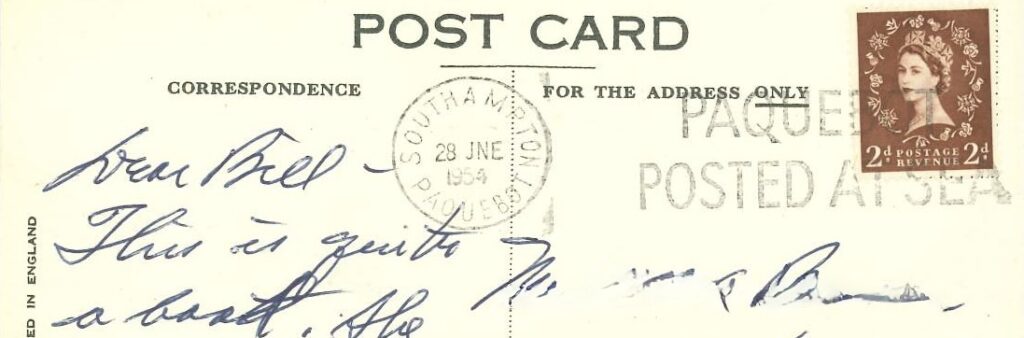

We learn from the featured postcard that the history of shipping, international commerce, and communication are closely related. Advancements in ship design, construction material, and navigation technologies not only speed up travelling time but also guarantee reliable scheduling of goods and mail. Initially, the main function of the river and oceangoing vessels was to carry goods and mail, passenger accommodation was limited. The term packet boat refers to a government-chartered vessel that carries mail and dispatches between two ports on a fixed route. Early packet boats were medium-sized vessels for domestic carriage. The French word paquebot means ‘steamboat’ but refers to an ocean liner. A mail with the hand stamp “PAQUEBOT” means the item was posted at sea, like the postcard below.

On the other side of the postcard was a picture of the Cunard Line RMS Queen Mary. RMS stands for Royal Mail Ship. The ship travelled between Southampton and New York and Halifax, Nova Scotia from 1936 to 1967. Cunard Line, originally the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, was a Southampton-based shipping company. It was the first company to obtain a transatlantic mail contract from the British government.

The 19th century saw the emergence of a new form of economy: the cruising industry. Some shipping companies shifted their focus from freight and mail delivery to passenger transportation. While speed continued to be a concern, ship design and construction now prioritized passenger comfortby including different on-board activities and entertainment and comfortable accommodations. An exemplar of cruising is the Cunard Line, which owns many massive, luxurious cruise ships A more well-known name in Asia is the P&O, that is, the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company. Founded on 31st December 1840, the four colors of P&O’s flag reflect its primary market in the early days: the Iberian peninsular (white and blue represent Portugal and yellow and red Spain). Later, the company’s business included the Eastern routes to India, Southeast Asia, China, Japan, and Australia.

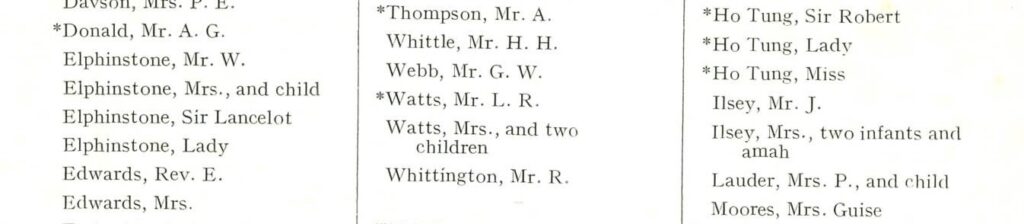

Cruising developed rapidly and by the early 20th century, there was no lack of superliners like the Cunard Line’s RMS Lusitania, RMS Mauretania, and RMS Queen Elizabeth, to name a few. Cruising emphasizes passenger experience so speed was no longer the determining factor. The steadiness of the ship and the overall travel experience took precedence instead. Some people describe cruise ships as “floating cities”. The analogy is quite appropriate if we look at the number of ports of call of the 15,000-ton P&O liner SS Comorin: leaving London on 30th September 1932 and Marseilles on 7 October, then heading for Malta, Port Said, Aden, Colombo, Penang, Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Yokohama, and Kobe. Famous and important people were, of course, the target customers of such ships. Aboard SS Comorin, for example, the passengers included H.H. Sir Charles Vyner Brooke (1874–1963), G.C.M.G., the last White Rajah of the Raj of Sarawak. Some of the passengers were from Hong Kong. Sir Robert Ho Tung Bosman (Chinese name: 何ho4東dung1; 1862–1956) was a Eurasian whose father Charles Henry Maurice Bosman was of Dutch Jewish background and his mother was a Chinese. He was nicknamed 香hoeng1港gong2大daa6老lou2 ‘the Big Brother of Hong Kong’, a name that reflected his wealth and position in Hong Kong. He was the chief compradore of Jardine, Matheson & Co. in 1894 and the first non-European to have residence on the Peak, a strictly European district at the time. He was knighted in 1915 and was conferred K.B.E. in 1955.2

Passengers included people from all walks of life such as the amahs, maids, and nurses. The term amah was used in China and Southeast Asia to call the female servants whose primary duty was “baby pidgin”, that is to take care of the children. Not only the passengers but also the crew was multinational. On board Sarie Brunei, a vessel plying between Singapore and Borneo, Ethel Colquhoun (1902) observes that:3

“The nationality of the Sarie Brunei was a most puzzling question. She was built at Glasgow, sailed from Singpaore, carried the Dutch flag, was Chinese-ownedm had a Danish captain (who was a British subject), a Dutch mate, a Scots engineer, a Chinese super-cargo and a crew of Malays. The English language was spoken on board, of course; but I leave you to image the variety of accent.”

A supercargo is a person employed by the cargo’s owner to take charge of the cargo. The lingua franca onboard Sarie Brunei is English but spoken in different forms. One of the varieties of English is now known as Chinese Pidgin English. Originating in Canton (now Guangzhou) in the 18th century, Chinese Pidgin English is an early variety of English to facilitate trade between the Chinese and the Westerners. Various socio-political reasons inside and outside China resulted in waves and waves of Chinese immigration to America, Peru, Cuba, Australia, and Southeast Asia in the 19th century. In her narrative, Colquhoun describes the interaction between two Chinese: Ah Ting, her servant and Ah Fong. At the end of the trip, Ah Fong condemned Ah Ting for making troubles onboard the ship, saying:4

You velly dirty sneak-pig-damn-dog! Makee muchee tlouble this side! My velly glad you go ’way chop-chop.

Although sharing the same written language, the spoken languages of different provinces in China may not be readily intelligible. As a lingua franca, Chinese Pidgin English was used not only between Chinese and Westerners but also between Chinese from different provinces of China like Ah Ting and Ah Fong. For two hundred years, the language functioned as an effective means for cross-cultural communication. Chinese Pidgin English effectively disappeared in Hong Kong around the 1960s/70s; however, bits and pieces like chop-chop ‘quick’ remind us of its legacy.

1. Staff, Frank. 1956. The Transatlantic Mail. London: Adelard Coles.

2. Holdswoth, May and Christopher Munn. (Eds.). 2012. Dictionary of Hong Kong Biography. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

3. Colquhoun, Ethel. 1902. Two on Their Travels. New York: A. S. Barnes & Co.

4. Li, Michelle & Stephen Matthews. 2024. Chinese Pidgin English in Southeast Asia: Contexts of use and influence. In Andrew Moody (ed.), Handbook of Southeast Asian Englishes, pp. 75-96. Oxford: Oxford University Press.