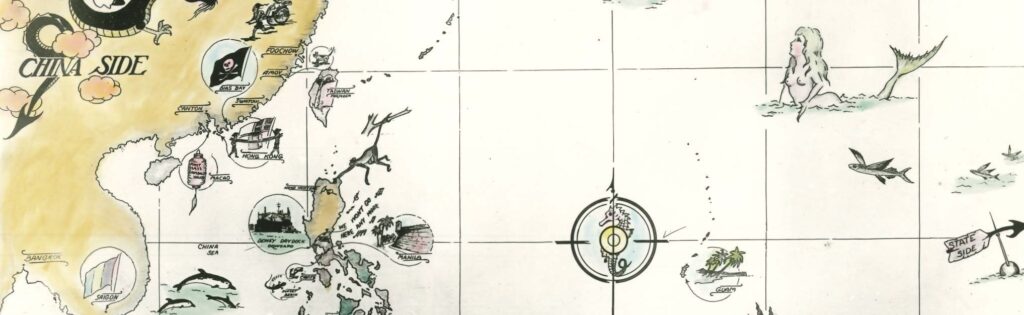

In 1784, the first merchant ship of the newly established United States of America – Empress of China – set sail from New York to Canton (Guangzhou) of China, the only Chinese port opened for foreign trade at the time. Following the conclusion of the First Opium War (1839-1842), China was forced to open more trading ports, they were Amoy (Xiamen), Foochow (Fuzhou), Ningpo (Ningbo), and Shanghai in addition to the existing port at Canton. Hong Kong Island was also ceded to Britain. Transpacific connections, especially between China and America, became increasingly prominent. Aside from trade, U.S. military involvement in the eastern side of the Pacific also became more and more prominent. The featured image above is a 1934 decorated map showing the Asiatic Station of the U.S. Navy in Asia. Still used in English today, Stateside means ‘related to the U.S.’ and ‘in or to the U.S.’ This use of side is a characteristic feature of Chinese Pidgin English in which position, location, or place is indicated by side instead of prepositions as in China side on the other side of the Pacific.

USS San Jacinto left New York in 1855 for China in order to participate in the Second Opium War. William Maxwell Wood was the ship surgeon. The ship arrived at Canton in 1856, when China was fighting with Britain and other western powers again. Despite such tension, foreign ships still had to rely on local people for provisions and services. One such assistance was laundry which was usually done by the boat people who lived on boats. Assing, the father of a boat family, worked as the laundry man for San Jacinto. Once, Assing expressed his worries to Wood, saying “my very much fear.” Wood assured him that the Americans would protect him so he needed not be afraid. However, Assing responded that when the ships left China, he would be in trouble. In Assing’s words:1

“Byme-by, you go New York side—’Merrikey side; my stay China side—mandarin cutee off my head, all my catchee, now forty-five dollar one moons; no, enough.”

Assing was speaking in Chinese Pidgin English, a medium of communication that emerged in the 18th century that allowed Chinese and foreigners to communicate with each other. Byme-by comes from by and by in English and means ‘in a short period, soon’. Moon represents ‘month’. Facing the risk of being executed and his properties confiscated, Assing gave a value of his head as below.

“Pay five hundred dollar my wife—my children—can take Assing’s head.”

In the short response of Assing, side occurred three times – New York side, ’Merrikey (America) side, and China side. You may also notice the lack of prepositions before the locations. So the main function of side in the pidgin is to indicate location. The use of side is not random but corresponds to a pattern found in Cantonese grammar. Cantonese is the principal dialect spoken in the Guangdong province, where Canton and Hong Kong are situated. Apart from English, Cantonese is another language that contributes much to the grammar of Chinese Pidgin English. Because of the social and political instabilities in Canton during the Second Opium War, many foreign residents moved to Hong Kong, already a British colony by this time and possessed a natural deep harbour, which quickly developed into an important trading port. Remnants of pidgin English features could still be found in 1960s–70s Hong Kong. Since Hong Kong is predominantly a Cantonese society, many foreigners found it necessary to learn Cantonese. For example, Elizabeth Latimore Boyle prepared a Cantonese textbook in 1970, and in one of the lessons Boyle compared the colloquial expressions Hongkong side and Kowloon side with the Cantonese word for side. Her comment was as follows.2

“People in Hongkong identify places as being ‘on the Hongkong side’ or ‘on the Kowloon side’. Kowloon and Hongkong are on opposite sides of the Hongkong Harbour. Hèunggóng nī bihn ‘on the Hongkong side’ [Hongkong this side] is said from the standpoint of a person who is on the Hongkong side. To him the Kowloon side would be Gáulùhng gó bihn ‘on the Kowloon side’ [Kowloon that side].”

The word bihn (in modified Yale romanization) means ‘side’, and can be written as 邊 or 便. The demonstratives nī and gó correspond to English this and that. The word bihn (or bin1/6 in Jyutping romanization) also forms other locatives such as soeng9 ‘top’ and haa6 ‘down’ as in soeng6 bin1/6 ‘above, upstairs’ and haa6 bin1/6 below, downstairs’. The ship surgeon, William Maxwell Wood, also noticed such expressions in pidgin English. Havee got means ‘exist, there is’. In other words, the question was ‘Is the Missus there?’

“Missus havee got?

No got. Havee got topside. Havee got downside

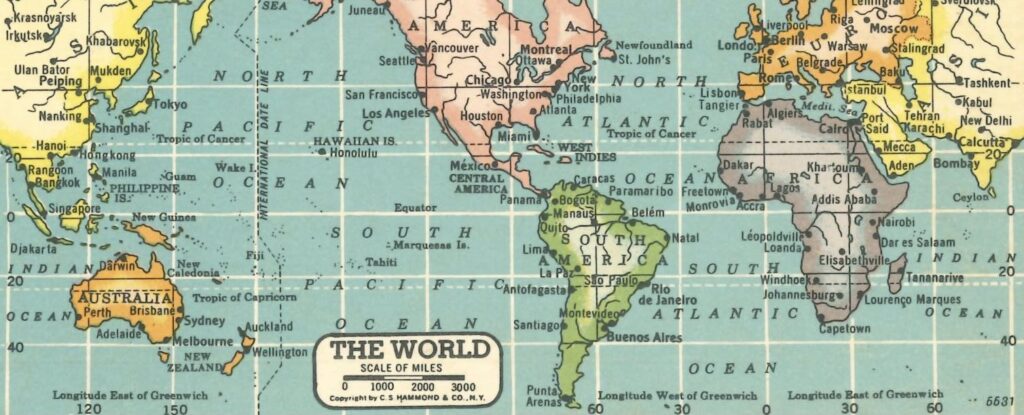

While language employs different linguistic means to express location, the exact location of a place on the Earth is indicated in a standard means. For example, the geographical position of Hong Kong is between Latitude 22°08’ North and 22°35’ North, Longitude 113°49’ East and 114°31’ East.3 These numbers represent the coordinates of latitude and longitude which are universally recognized. Today, many tools allow us to tell our exact location. However, such precision in geographical position has taken centuries to evolve. Latitude is measured by comparing your position on Earth and the position of either the Sun or the North Star (Polaris). Determining longitude posed a serious challenge for ship navigators as travelling from east to west or vice versa required knowledge and skills in measuring time difference. The current standard 0° longitude (line of longitude is also called meridian), known as the prime meridian, is at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. The prime meridian sets the Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) from which time zones are divided, for example, Hong Kong is UTC +8 hours. The 180° longitude is used as the basis for the International Date Line (IDL), which is a line separating one calendar day from the next. The prime meridian and the 180° longitude/meridian form a circle and divide the Earth into eastern and western hemispheres.

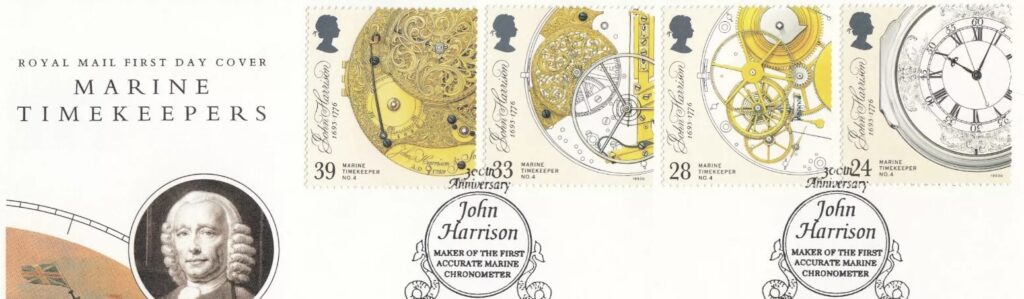

Before the longitude problem was solved, dead reckoning was a common method to calculate the local time. However, this method often produced significant errors. In order to minimize the perils of long voyages, the Parliament of Britain passed the Longitude Act in 1714. It offered monetary rewards to anyone who could find the solution to determine a ship’s precise longitude. One of the reward recipients was an English carpenter and clockmaker called John Harrison (1693–1776).

Unlike on land, Harrison realized that he had to design a portable clock that could resist variations in pressure, temperature, humidity, and motion of a ship while at sea. It took him three decades to produce the world’s first marine chronometer. Harrison brought his first attempt, known as H1, to London in 1735. In 1736, H1 was tested in a sea trial aboard HMS Centurion for Lisbon; the precision of H1 in the trial was impressive and Harrison was awarded £500. Harrison produced his second sea clock, H2, two years later but this clock was never tested in sea. In order to correct the flaw of H2, Harrison took 19 years to produce his third attempt – H3. At last, in 1759, H4, which measured five inches in diameter and weighed only three pounds, was born. According to the Longitude Act, the timekeeper must be tested on a voyage to the West Indies. The sea trial to Jamaica was conducted between 1761 and 1762. However, the Commissioners of Longitude were not completely convinced of the results and so a second trial was arranged. While Harrison was perfecting the design and precision of H4, other methods were developed to measure longitude at sea, such as measuring the lunar distance with a sextant and Jupiter’s satellites. In the second trial to Barbados in 1764, Harrison’s H4 would compete with other methods. H4 won and was later referred to as the first marine chronometer. Solving the longitude problem made commercial travel safer, faster, and cheaper. In 1884, Greenwich was adopted as the prime meridian at the International Meridian Conference held in Washington, D.C.4

The cardinal directions—north, south, east, and west—are used beyond their denotative meanings as human societies evolve. For example, people say that China and the United States represent the eastern and the western cultures respectively. Although imaginary, the latitude and longitude are clearcut lines, the social and cultural conceptualization of “east” and “west”, on the other hand, are complex and unstable, producing various effects like differentiation, opposition, coexistence, and fusion.

1. Wood, William Maxwell. 1859. Fankwei; or, the San Jacinto in the Seas of India, China and Japan. New York: Harper & Brothers.

2. Boyle, Elizabeth Latimore. 1970. Cantonese; Basic Course Volume 1. Washington, D.C.: Foreign Service Institute.

3. Lands Department. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government.

4. Sobel, Dava. 1995. Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time. London: Fourth Estate.