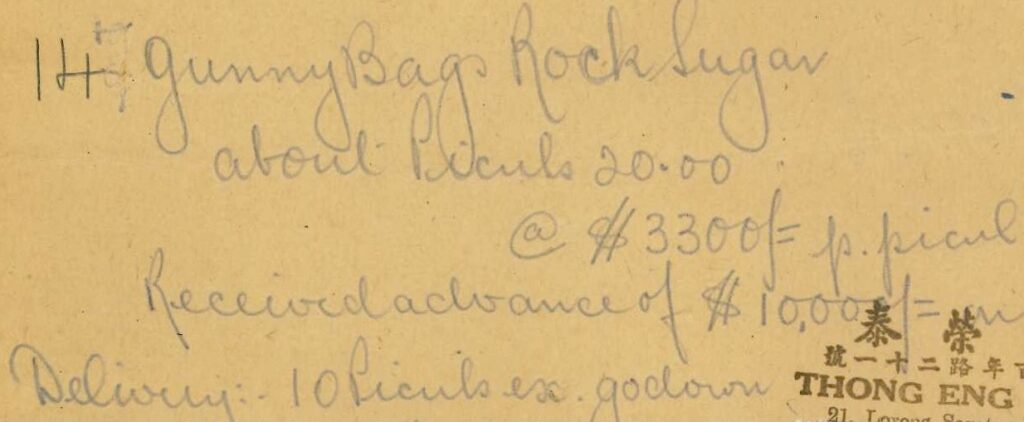

The featured image is the receipt from a shop in Penang for an order of rock sugar. Rock sugar 冰糖 (Cantonese: bing1 tong4) is a kind of crystalized sugar extracted from sugar cane. It is less sweet than granulated white sugar, but it is often used in Chinese dishes and desserts. In Chinese, there is a proverb about the seven daily necessities of traditional Chinese households. The proverb says:

| 開 | 門 | 七 | 件 | 事 | |||||

| hoi1 | mun4 | cat1 | gin6 | si6 | |||||

| open | door | seven | CL | item |

| 柴 | 米 | 油 | 鹽 | 醬 | 醋 | 茶 | ||

| caai4 | mai5 | jau4 | jim4 | zoeng3 | cou3 | caa4 | ||

| firewood | rice | oil | salt | sauce | vinegar | tea |

The seven essential items are 柴 ‘firewood’, 米 ‘rice’, 油 ‘oil’, 鹽 ‘salt’, 醬 ‘sauce’, 醋 ‘vinegar’, and 茶 ‘tea’. Today, firewood is of course replaced by gas or electricity, the other six items remain essential ingredients in Chinese food culture. Interestingly, sugar, which can be found in many foods now, is not mentioned. In the West, massive production and consumption of sugar are closely related to the Age of Discovery of the 15th century.

The Age of Discovery was an era of experimentation, excitement, and innovation. New lands and uncharted sea routes were discovered first by the Portuguese and Spanish, then by the Dutch, English, and French. In 1419, the Portuguese found and claimed an island located in the North Atlantic and the next year Portuguese settlers began to populate the island. The Portuguese named the volcanic island Medeira and found that the soil was particularly suitable for cultivating crops. Today, Medeira is well-known for its wine, but in the 15th century, the main engine of the economy on the island was sugar cane cultivation. Madeira succeeded in becoming the largest sugar producer for the European market. However, a far-reaching impact of the large-scale plantation system in Madeira was that it served as the model of sugar cultivation replicated throughout the Atlantic, like in Brazil, São Tomé, and the Caribbeans, where numerous enslaved Africans worked in European-owned plantations.1

Though the scale of sugar cane cultivation in Hong Kong was limited, sugar refinery was one of the major industries in the early development of the city. In the late 19th century, there were two major sugar plants in Hong Kong – China Sugar Refinery owned by Jardine, Matheson & Co. and Taikoo Sugar Refinery established by Butterfield and Swire, more well known by its Chinese name Taikoo 太古. Compared with the other well-established hongs (i.e., firms) such as Jardine’s and Russell’s, John Samuel Swire (1825–1898) set foot in China relatively late, arriving in Shanghai only in 1866. Soon, Swire partnered with Richard Butterfield and established Butterfield & Swire (now Swire Group). With an acumen business mind, successful investments in shipping, sugar refinery, and dockyard not only earned J. S. Swire money but also prominence among foreign trading companies at the time. Taikoo Sugar Refinery began operation in Quarry Bay in 1884 and ceased production in the 1970s. For nearly a century, this Hong Kong-based sugar refinery served as a world-leading sugar producer for the local and world markets. The brand ‘Taikoo Sugar’ is still an essential item in many households.2

As we can see from the featured image above, rock sugar was weighed in a traditional Asian unit called picul. The term picul isderived from Malay pikul ‘a load or burden’. In Chinese, picul is represented by the character 擔. As a verb, 擔 (Cantonese: daam1) means ‘to carry things with a pole over the shoulder’ or ‘to take responsibility.’ As a noun, the character is pronounced as daam3 and means ‘a load’. How heavy is one picul? Traditionally, one picul equalled 100 catties; and one catty was 1 and 1/3 pounds (or 0.60478982 kilogram). So one picul is 133 and 1/3 avoirdupois pounds, which is equivalent to 60.478982 kilograms.3 Besides picul,other weight measures like catty, tael, and candareen are also derived from the Malay language.

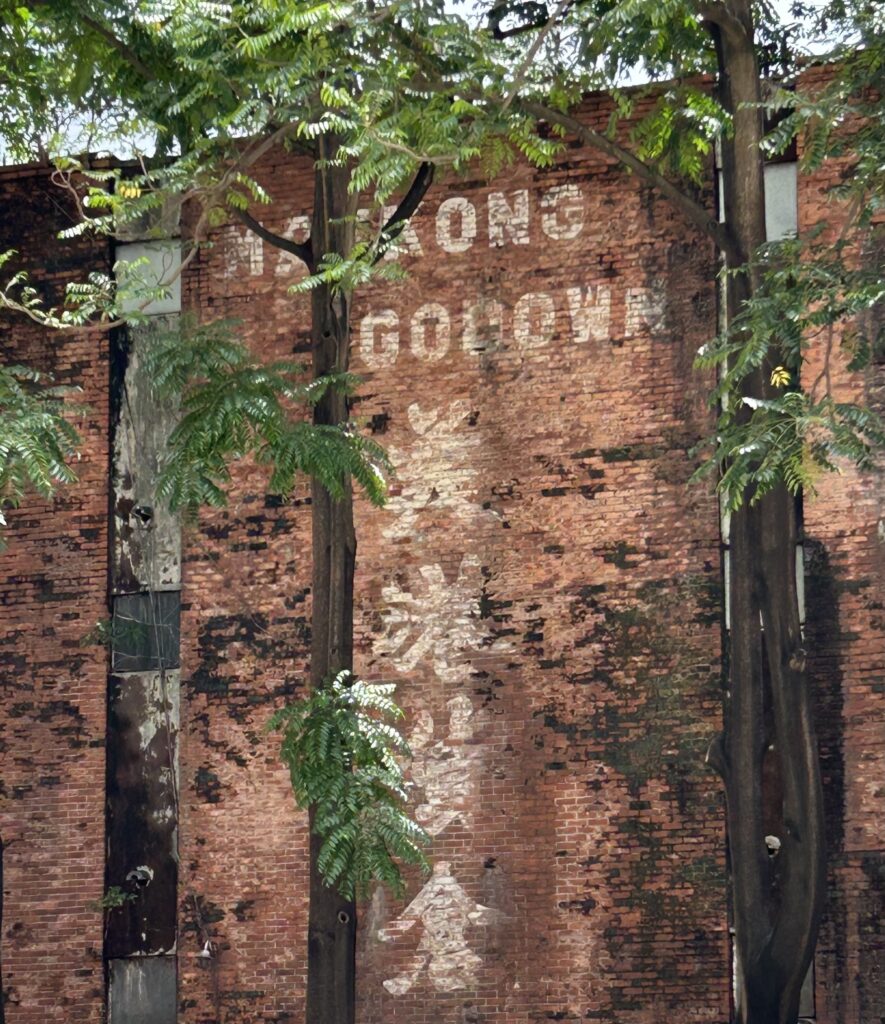

The word godown as seen on the featured receipt and the photos on the left refers to the warehouse. It is derived from the Malay word gadong ‘store-room’ (current spelling gudang). An Indian origin can also be found in languages like Telugu giḍaṅgi and Tamil kidaṅgu, both denote ‘a place where goods lie.’ 4 Wharves and godowns were important infrastructures to facilitate the loading and storage of goods for import or export. The Taikoo Wharf located in Guangzhou is now a heritage site. In Hong Kong, the popular meeting point 五枝旗桿 (Cantonese: ng5 zi1 kei4 gon1) ‘the five flags poles’ in Tsim Sha Tsui is where The Hongkong & Kowloon Wharf & Godown Co. Ltd. (founded by Sir Paul Chater in 1886) used to be located. Foreign firms like Butterfield & Swire as described below employed different Chinese staff to work in these facilities.5

“The Hong Kong office employed the comprador, two shroffs (cashiers, or accounts), a writer, two shipping and two godownmen, three godown assistants, a watchman, three office boys, three ‘office coolies’, a watchman for the office and four ‘chair coolies’ (presumably for the Hong Kong senior staff).”

Among these Chinese employees, the comprador or compradore was the one who juggled between the taipans like John S. Swire and the Chinese staff of a foreign firm. Standing between the East and the West, the comprador(e) tried to find any common ground between the two cultures. The responsibilities of the comprador(e) were varied and heavy. He would take accountability for the Chinese staff’s duties and conduct; he would also assist the taipan in handling the intricacies of doing business with the Chinese.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, communication between the taipan and the comprador(e) was conducted mainly through the medium of Chinese Pidgin English, a variety of English combining features of English and Cantonese. The dialogue below is a specimen of an exchange between a taipan and a comprador(e).6

Taipan: How fashion that chow-chow cargo he just now stop godown inside?

Compradore: Lat cargo he no can walkee just now. Lat man Kong Tai he no got ploper sclew.

Taipan: How come you talkie sclew no ploper? My have got sclew paper safe inside.

Compradore: Aiyah! Lat sclew paper he no can do. Lat sclew man he have go Ningpo more far.

The taipan is surprised to see that the chow-chow (assorted, mixed) cargo is still lying inside the godown. In addition to meaning ‘to eat’ and ‘food’, chow-chow also refers to a miscellaneous of things. The comprador(e) was asked for an explanation – how fashion ‘why, how come’. In order to load the goods onto the vessel and leave the Chinese port, sclew, i.e., security, must be obtained first. The taipan is confused by the reply because the sclew paper is in his safe. The comprador(e) explains that the sclew paper is of no use now because the security man Kong Tai has absconded to Ningpo. A final grammatical feature is related to the use of he. In the pidgin, the pronoun he stands for all the third-person pronouns in English. But what is peculiar about the instances of he in the dialogue is that they are referentially identical to the subject noun phrases preceding he. In other words, these sentences show subject doubling which probably functions to mark focus or topic.

1. Greenfield, Sidney M. 1977. Madeira and the beginnings of New World sugar cane cultivation and plantation slavery: A study in institution building. Comparative Perspectives on Slavery in New World Plantation Societies 292(1): 536-552.

2. Crisswell, Colin N. 1981. The Taipans: Hong Kong’s Merchant Princes. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

3. Hong Kong e-Legislation Cap. 68 Weights and Measures Ordinance.

4. Yule, Henry and Arthur Coke Burnell. 1886. Hobson-Jobson Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms. London: John Murray.

5. Bickers, Robert. 2020. China Bound: John Swire & Son and Its World, 1816-1980. Bloomsbury Publishing.

6. Crow, Carl. 2007. (First published in 1940). Foreign Devils in the Flowery Kingdom. Hong Kong: Earnshaw Books.