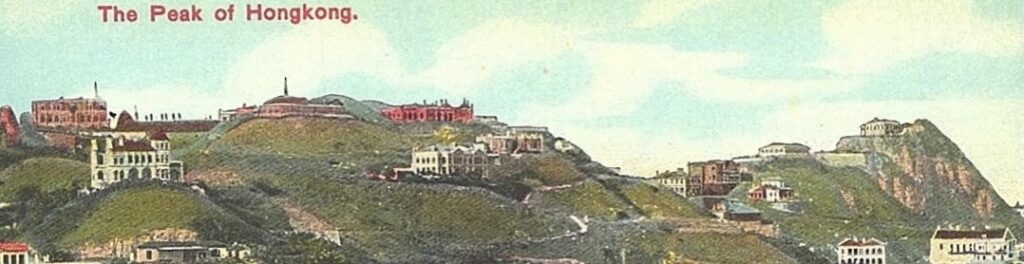

When Granville Sharp (1824–1899) arrived in India, he joined the Commercial Bank of India. On 2 November 1858, he married Matilda Lincolne Sharp (1829–1893) in Bombay, India. Not long after their wedding, the Sharps arrived in Hong Kong on 25 December 1858. After working for a short time in the Hong Kong office, Sharp left his job in the bank and actively engaged in different businesses, including real estate, bill and bullion brokerage, and mortgage. He was also one of the founders of the Dairy Farm Company, which was incorporated in 1886 in Hong Kong. The Sharps were among the first families to reside on the Peak – then a Europeans-only district.1 Like many European housewives, Matilda spent most of her time running the house, but she also enjoyed writing. The private letters she left give us glimpses of lives in 19th-century Hong Kong. In one of her letters, she described how she spent the day.

“We rise and walk before breakfast—that and family worship at nine, down to business at ten. Then I finish my private devotions, go to the store closet, give out to cook and settle accounts of the previous day, write journal etc., and find amah her work to do; visits at noon, either receiving or going out. Tiffin at one-thirty, when I see husband and Mr. Davis again for half an hour, alone again till five, either writing or something else. Then a walk with my precious husband, meet at dinner at seven, and spend the evening together either reading, tatting [relating to lace-making] or netting. I use my pen much more than my needle—indeed I cannot bear to sit and sew by myself.…” (January 1860)

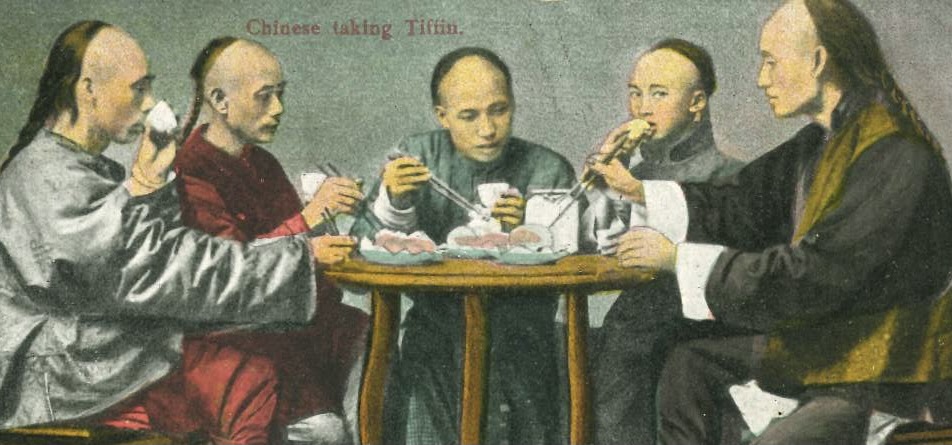

Like today, three regular meals were served. However, instead of calling the midday meal “lunch” Matilda called it “tiffin”. Tiffin is an Anglo-Indian term created as a result of the copresence of the English and Indians during the British India era.

Like most European families in Hong Kong, the Sharps employed Chinese servants to help them with the household chores. The “boy”, regardless of age, was the male servant, and the “amah” was the female servant who attended to the personal needs of the mistress as well as acting as the nanny. Communication between the Westerners and the Chinese was conducted through the medium of Chinese Pidgin English – a variety of English emerged in Canton as a means for people speaking mutually unintelligible languages to communicate. Matilda gave us an example of this kind of interaction in one of her letters in January 1860.

Matilda: ‘Amah go talky boy, talky Mr. Sharp and Mr. Davis tiffin ready, talky me when they come.’

Boy: ‘Mr. Davis down-side, come top-side’

This means of communication was the norm for both Chinese and foreigners alike in the 19th century. So, let’s take a look at the pidgin sentences in the dialogue. The word talky, apparently derived from English talk, can represent several verbs of speaking such as talk, tell, speak, etc. depending on the context. In terms of concreteness of meaning, content words are more important than function words. That’s why in tiffin ready,the copular verb be is left out as it contributes little to the overall meaning. You may also notice that the expressions down-side and top-side sound quite un-English. The meanings of down-side and top-side are ‘below, downstairs’ and top-side ‘above, upstairs’ respectively. What is puzzling is the use of -side after down and top.While the usage is not found in English, Cantonese grammar gives us a hint. When referring to positions, the characters 便 bin6, 面 min6 ‘or 邊 bin6, all could mean ‘side’, are added after direction words like 上 soeng6 ‘up’, 下 haa6 ‘down’, 左 zo2 ‘left’, 右 jau6 ‘right’; thus, giving expressions such as 上便 soeng6 bin6/上面 soeng6 min6/上邊 soeng6 bin6 for ‘above, upstairs’ and 下便 haa6 bin6/下面 haa6 min6/下邊 haa6 bin6 for ‘below, downstair’. So, the use of -side in top-side and down-side is based on these expressions of position in Cantonese.

Though Chinese Pidgin English would be a ready solution for communication problems, Matilda Sharp was keen to learn Chinese, namely the local language – Cantonese – too. She took Cantonese lessons three times a week.1 As the saying goes, practice makes perfect. However, when it came to practising Cantonese, she faced problems like the one below.2

“I seldom speak anything else and insist on the servants speaking Chinese to me. I really feel we are getting on a little and it is so interesting to go shopping. The other day I was very indignant about the impoliteness of a shopkeeper. I spoke to him in Chinese and he would answer in English. At last I said, ‘I wish you to speak Chinese to me. I want to learn.’ He smiled and touched his ear, ‘Too muchee trouble pain ee give my ear to hear you speak Chinese. You just now begin. Want a little more learn then I can speak.’ I said, ‘If you don’t speak Chinese, I don’t buy.’ They do not like us learning as it gives them such an advantage over us if we have difficulty understanding what they say, or not to make yourself understood by them.” 2

The Chinese shopkeeper was, of course, speaking pidgin English. He told Maltida that it was very difficult to understand her Chinese as she was a beginner. She had to learn more Chinese, then they could communicate in Chinese. The Sharps lived in Hong Kong for three decades and Matilda Sharp died in 1893. Granville Sharp endowed a hospital on the Peak and named it after his wife. The hospital opened in 1907 and today it is known as Matilda International Hospital.

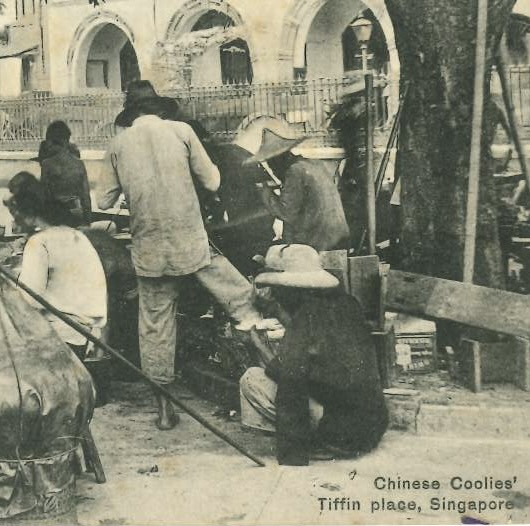

Now, back to the word tiffin. The word emerges as a result of the cultural blending of English and Indian. Although usually regarded as an Indian word, the Hobson-Jobson Glossary suggests that tiffin, as used in India to refer to ‘luncheon’, originates from the English participial noun tiffing of the verb to tiff ‘take off a draught’. The participial noun tiffing, meaning ‘eating or drinking out of meal-times’, becomes regularly spelt as tiffin. 3 The fashion of taking tiffin spread to the Far East as the British Empire expanded towards the Far East. The British East India Company established the Straits Settlements comprising Penang, Malacca, and Singapore in 1826. So, tiffin became fashionable in Southeast Asia too. In Hong Kong, the popularity of tiffin during colonial time is evident in Matilda Sharp’s account above. The Shanghai Tiffin Club, established after the First Opium War, was the place where the expatriates gossiped about international and local affairs during the “tiffin hour”.4

1. Holdswoth, May and Christopher Munn (eds.). 2012. Dictionary of Hong Kong Biography. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. pp. 390-391.

2. Hoe, Susanna. 1991. The Private Life of Old Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. p. 128.

3. Yule, Henry and Arthur Coke Burnell. 1886. Hobson-Jobson Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms. London: John Murray.

4. French, Paul. 2006. Carl Crow – A Tough Old China Hand. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.