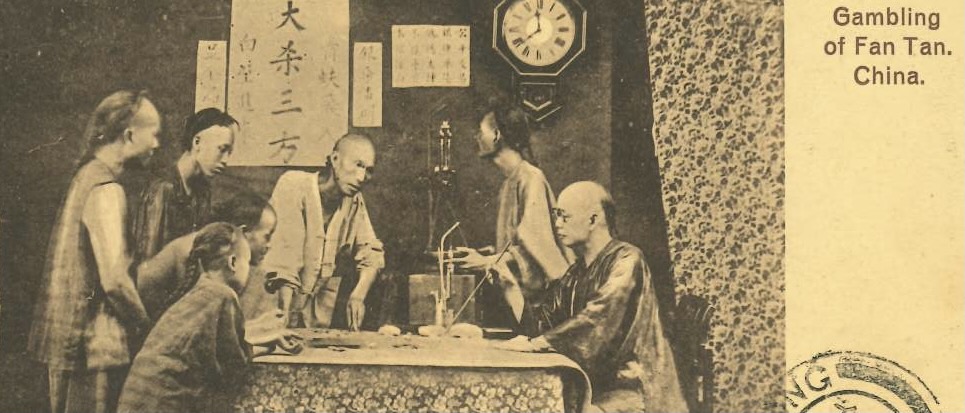

An aspect of Chinese lives that Western writers of the 19th and 20th century often described was gambling. During his service in Singapore, J.D. Vaughan a variety of ways that Chinese gambled and mentioned that the Chinese had “an inherent love for gambling”.1 Chinese gambling games take many forms and show different degrees of sophistication. The multi-player game mahjong, for instance, is a very interactive game and requires good memories, accurate calculation, and tactics in order to be a proficient player. Other games such as fan-tan (番攤) is more of a game of chance. The essence of the game is represented by its name: 番 (Cantonese pronunciation: faan1) means ‘number of times’ and 攤 (Cantonese pronunciation: taan1) means ‘to divide’.

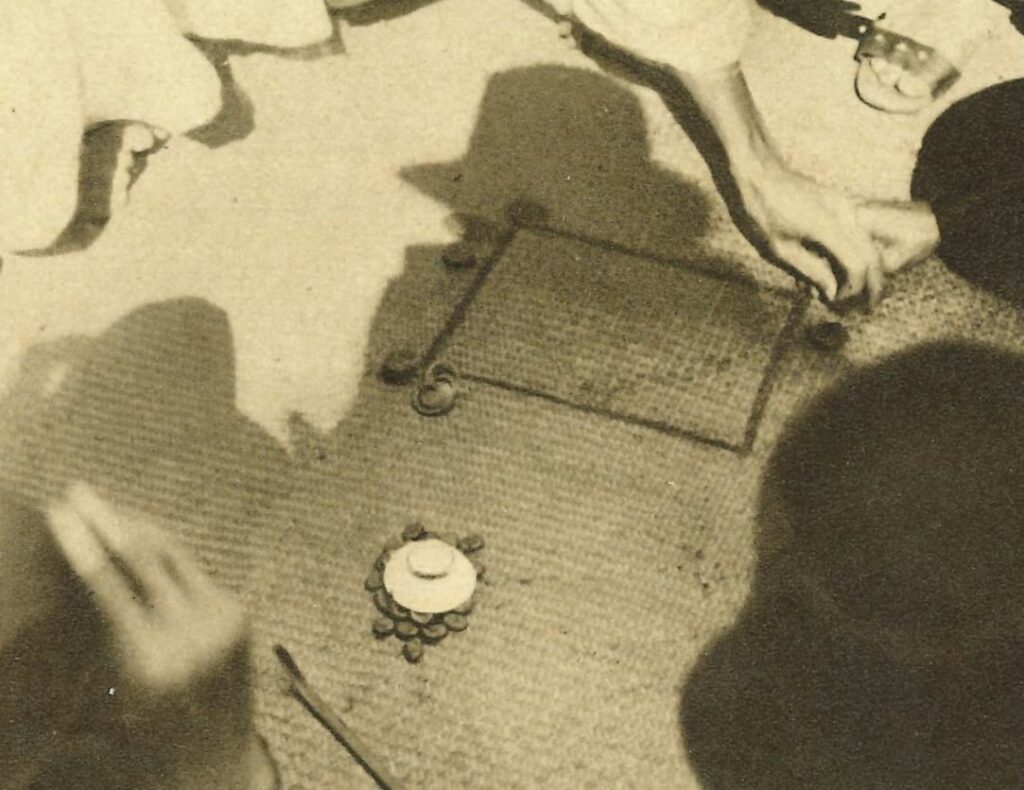

The tools for playing fan-tan are simple: a pile of coins or beans to be divided, a small bowl for covering coins or beans, a stick the croupier uses to divide the coins/beans. The method of the game is straightforward – the gamblers place bets on how many coins or beans will be left after they are drawn out, four pieces at a time. Herbert A. Giles, a British diplomat in China before becoming a professor of Chinese language at the University of Cambridge, explained how the game was played as follows.2

“A pile of the coin is covered with a bowl, and the players stake on what the remainder will be when the heap has been divided by 4, namely 1, 2, 3, nothing. The croupier then counts the whole rapidly out, deducting eight per cent from the winnings of each player for the good of the house. Fan here means “number of times,” and t’an “to apportion,” in allusion to the payment of stakes so many times the original amount according to circumstances.”

Since it was so convenient to get the tools and there was almost no restriction on the location for playing, the game became popular among Chinese migrants who settled in places like Penang, Singapore, London, San Francisco, New York, etc. Fan-tan was banned in many places, so people had to play the game in secret. During visits of inspection of the Chinese residences, it was common to find fan-tan tables hidden inside Chinese shops, as in the description of the conditions of two Chinese shops at Goulburn Street and the neighbourhood in Sydney.3

“No. 179, Bow Sing Tong. —Front premises occupied as a medicine shop, but no medicine in stock; fan-tan table in room behind, from which a narrow passage gives access to three other houses; a store-room, a bed-room, recking with dampness, devoid of ventilation, and containing two beds, also a W.C. and a lottery-bank; as clean as such premises could well be.”

“Sun Sam Kee. —Strongly barricaded doors between front shop and rear rooms, containing fan-tan tables; exit through three doors to Queen-street; escape across the roof in various directions for gamblers in case of surprise. The entire house presents the appearance of a rabbit warren; upstairs windows strongly barred; premises clean.”

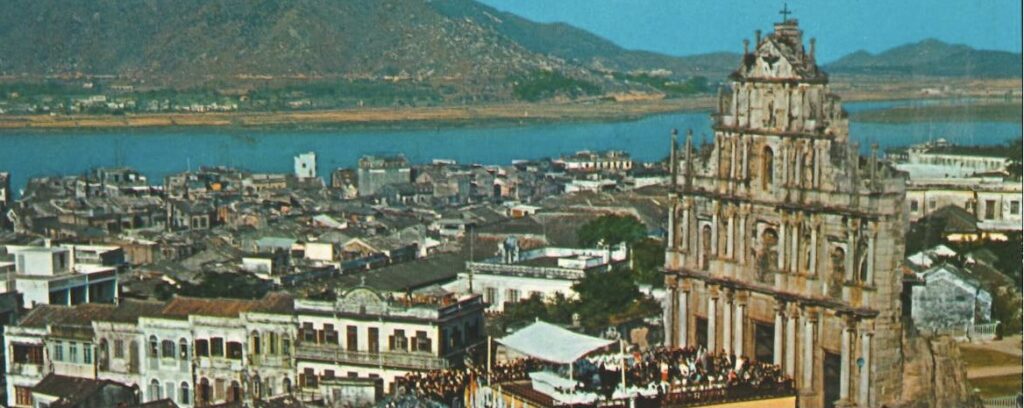

Unlike the places mentioned above and Hong Kong, the Portuguese government legalized fan-tan syndicate in Macao in 1849. The primary reason was to increase government revenue, but a side-effect was the long history of connection between Macao and gambling. Macao became the centre of gambling in Asia and was referred to as the “Monte Carlo of the East”.

Aleko E. Lilius (1890–1977) was born in Russia. He was a journalist and author of the book I sailed with Chinese Pirates, in which he recounted his extraordinary adventures of journeying with the Chinese pirates in an armoured pirate junk and meeting exceptional people including the Chinese female pirate named Lai Choi San in the 1920s in Macao. The largest “casino” in Macao at the time was Sun Tai gambling house, which was a three-storied fan-tan den. In one of his visits to Macao, Lilius saw a giant Chinese man sitting opposite him in Sun Tai, playing fan-tan. Lilius was curious about this man because he bet heavily and won every bet. Lilius asked his acquaintance, nicknamed “this Chinaman”, about him.4

Lilius: Who is he?

“This Chinaman”: Oh, vellee, vellee rich man. He find plentee gold, old gold, Spanish gold, many years ago.

Lilius: Where?

“This Chinaman”: Oh, far away in Kaulan somewhere. Ship sink many years ago belong Poltuguese. Plentee gold. He coolie before, now vellee, velle rich.

Lilius: How rich?

“This Chinaman”: No savee—ten thousand, ten ten thousand, hundred ten thousand.

Lilius: He speaks English?

“This Chinaman”: Hong-Kong coolie English.

Vellee, meaning ‘very’, shows a typical way Chinese represent the “r” sound, namely replace it with “l”. Savee comes from the Portuguese verb saber ‘know’. After playing, the giant Chinese smoked opium on the couch. Lilius knew it was not “Chinese proper fashion” to disturb him at this moment, but he went ahead and greeted him in his best pidgin English. The Chinese replied,

Chinese: Sit down. Have pipe.

Lilius again broke the “Chinese proper fashion” by refusing the invitation. He hurled questions at the Chinese. However, the Chinese was too tired and preferred to entertained Lilius “bye’m bye”, i.e. by and by.

Chinese: Bye’m bye will tell. Not now. Too tiled. You play fan-tan now. I come back bye’m bye. We go topside my house.

With the introduction of Western-style games, fan-tan is no longer be as popular as before, but gaming and gaming tourism remain the largest sources of income for the Macao government. Macao, now rebranded as the “Las Vegas of the East”, is still the only territory within China where casinos are legal.

The glamour of casinos is hard to resist but failing to appreciate the real gem of Macao – an authentic place of “East meets West” would miss the point. In 2005, the Historic Centre of Macao, a collection of 22 historic sites, was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Some of the buildings and spaces included in the list are A-Ma Temple (媽閣廟), Leal Senado Building (市政署大樓), Moorish Barracks (港務局大樓 (formerly 嚤囉兵營)), Sir Robert Ho Tung Library (何東圖書館), Old Protestant Cemetery (基督教墳場), and Ruins of St. Paul’s (大三巴牌坊 (聖保祿教堂遺址)). The Macanese people, language and cuisine are exemplars of interbreeding of races, language, and culture. The term Macanese (Macaense in Portuguese) refers to the people of mixed ancestries – Portuguese fathers and Asia (mainly Chinese) mothers –in Macau. The language they speak, a creole language, is referred to by several names, Macanese/Macaense, Papiá Cristâm di Macau (“Christian speech of Macau”), Papiaçam, Maquista, and Patuá. Doci Papiaçam di Macau (澳門土生土語話劇團) is a drama group in Macao. Through writing and performing original plays in Macanese, the group hopes to preserve the Patuá and encourage people to learn and relearn this endangered language.

1. Vaughan, J.D. 1879. The Manners and Customs of the Chinese of the Straits Settlements. Singapore: Mission Press.

2. Giles, Herbert A. 1886. A Glossary of Reference on Subject Connected with the Far East, second edition. Hongkong: Messrs. Lane, Crawford & Co.; Shanghai & Yokohama: Messrs. Kelly & Walsh; London: Bernard Quaritch.

3. Votes and Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly During the Session of 1891-2, with the Various Documents connected Therewith. 1892.Vol. 8, p. 475. Sydney: Charles Potter, Government Printer.

4. Lilius, Aleko E. 1991. I sailed with Chinese Pirates. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.