Not having a chance to feel the “spicy breezes” of Ceylon? Maskee, try Singapore – a country that is also full of diversity and spicy food. Four official languages: English, Malay, Tamil, and Chinese are recognized in Singapore. The Chinese communities constitute 74.1% of the total population in Singapore. Many them arrived in Singapore as labourers from South China in the 19th century. They spoke a variety of Chinese dialects including Cantonese (Yue), Teochew (Chaozhou), Hokkien (Min), Hainanese, etc. After completing their labour contracts, many Chinese decided to stay in the colony. Some became entrepreneurs and formed the backbone of Singapore’s economic development. Making up 13.4% of the population, Malay is the second largest ethnic group in Singapore. As one of the earliest settlers in Singapore, Malay culture and language have a special place in the country. The national anthem of Singapore Majulah Singapura was composed in Malay. The Indians, though now accounting for just 9.2% of Singapore, are an inseparable part of the history and culture of Singapore. The anglicized name Singapore is of Sanskrit origin – Singha ‘lion’ and pura ‘city’, thus the lion city.

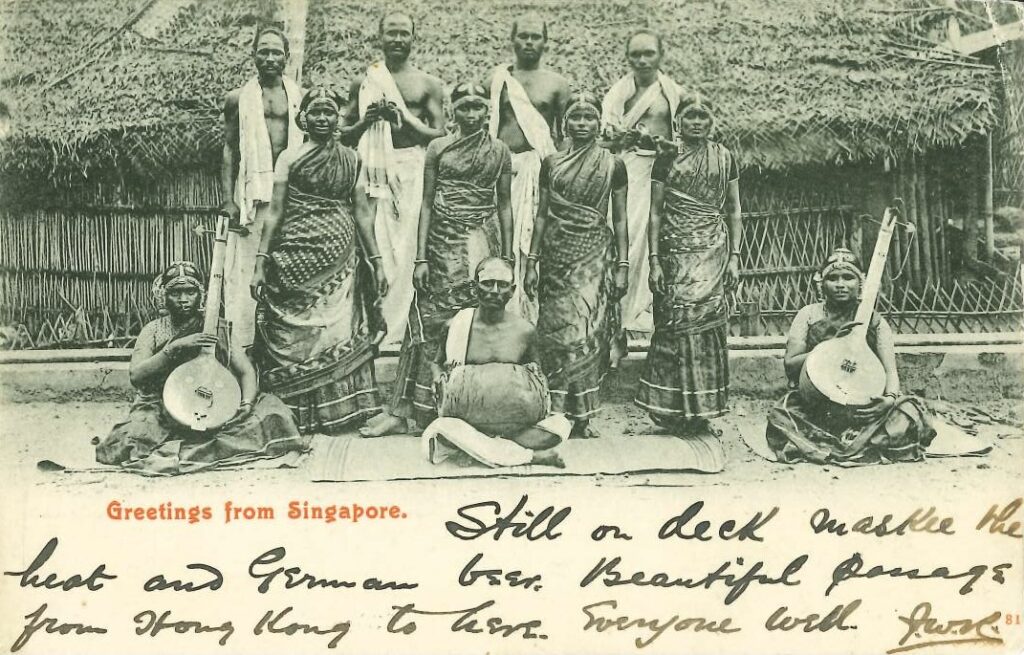

The postcard above was sent from Singapore via Hong Kong to Shanghai in 1907. The message: “Still on deck maskee the heat and German beer. Beautiful passage from Hong Kong to here. Everyone well” was not particularly special. However, the word maskee is intriguing. What could it mean?

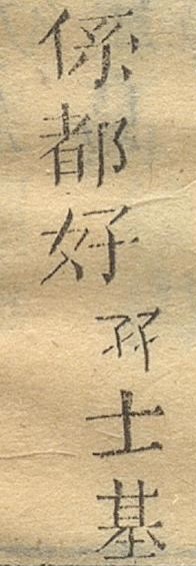

Maskee was a common word in the pidgin English spoken in Canton, Shanghai and Hong Kong. The meaning of maskee differed depending on the context of use, but generally it was translated as ‘Never mind, notwithstanding, all right, correct, nevertheless, however, but, anyhow’.1 In one type of pidgin English phrasebook called 紅毛通用番話 available in Canton (now Guangzhou), the pidgin equivalent of the Chinese phrase 係都好 ‘it is all right’ was 孖士基 maa1 si6 gi1 (i.e. maskee). Chinese Pidgin English was a lingua franca used between Chinese and Westerners in Canton and later Hong Kong and Shanghai. Another example of the use of maskee came from the book The Chinese and English Instructor, authored by the Cantonese merchant Tong Ting-kü (aka Tong King-sing).Though the book was primarily a Cantonese-English manual, some sections contained pidgin translations such as the example below.2

you wantchee makee roastee today ‘Do you want it roasted today?’

can no can ‘Can you do so?’

I fear no can ‘I am afraid I cannot.’

maskee tomorrow can do ‘Well, put it off till tomorrow.’

The current building of the Shanghai Club, now occupied by Waldorf Astoria Shanghai on the Bund, was built in 1911. The Club was exclusively for British taipans and other British residents. There was a joke related to the Shanghai Club, a place where men sometimes take refuge from their wives. One time, a wife was looking for her missing husband, so she called the hall porter of the Shanghai Club. Their conversation went like this.3

Female Voice: “That belong Hall Porter? Well, my wanchee savvy, s’pose my husband have got, no got?”

Chinese Porter: “No, missy, husband no got.”

Female Voice: “How fashion you savvy no got, s’pose my no talkee name?”

Chinese Porter: “Maskee name, missy, any husband no got this side anytime.”

This pidgin English dialogue showed some peculiar usages of the language. The copula verb be was normally absent. However, the belong could behave like a copula as in the woman’s first question ‘Are you the Hall Porter?’. S’pose came from suppose and was one of the few conjunctions found in the pidgin. In place of if, s’pose introduced conditions or hypothetical situations.The expressions have got and its negative form no got appeared several times in the dialogue. In this context, the woman was not referring to whether her husband had possessed anything. She was only interested in knowing if her husband was in the Club or not. In other words, have got here referred to ‘is here’ and no got ‘is not here’. Unlike English, which has different verbs for possession (have) existence (be),Chinese Pidgin English fused the two concepts. This kind of fusion can also be seen in Cantonese. In the following sentence, a single verb 有 jau5 expresses both existential and possessive meanings.

嗰到有櫃檯。你有問題可以去問。

go2 dou6 jau5 gwaai6 toi2, nei5 jau5 man6 tai4 ho2ji5 heoi3 man6.

there be counter you have question can go ask

‘There are counters over there. If you have questions, go there and ask.’

The first jau5 denotes existence of the counters (gwaai6 toi2), whereas the second jau5 refers to the possession (man6 tai4). In this respect, Chinese Pidgin English and Cantonese are grammatical similar.4 Interestingly, today we can sometimes hear Hong Kong people say something like There have a chair. The clever porter knew exactly how to respond to such questions from wives and gave the standard answer immediately without knowing whom the woman was looking for (maskee name ‘name doesn’t matter’).

As for the meanings of maskee, it has been generally attributed to usages in Portuguese like mas que ‘but that’, ainda que ‘even if’ and embora ‘although’. In the creole spoken by the Macaense community in Macau, the word masquímeans ‘in spite of, although, let it be’, for example Masquí seza ‘although it is like that’.5 Given the geographical proximity and trading network between Macao and Canton, it is possible that pidgin English maskee was based on the Portuguese spoken in Macao at the time.

1. Thompson, R.W. 1958. Let’s take Hongkong’s word. The China Mail, 13 September. Hong Kong.

2. Tong, Ting-kü. 1862. The Chinese and English Instructor. Canton.

3. Earnshaw, Graham. 2008. Tales of Old Shanghai. Hong Kong: Earnshaw Books.

4. Stephen Matthews and Michelle Li. 2013. Chinese Pidgin English. In: Michaelis, Susanne Maria & Maurer, Philippe & Haspelmath, Martin & Huber, Magnus (eds.) The survey of pidgin and creole languages. In “The survey of pidgin and creole languages”. Volume 1: English-based and Dutch-based Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Online version: https://apics-online.info/surveys/20

5. Fernandes, Miguel Senna and Alan Norman Baxter. 2004. Maquista Chapado: Vocabulary and Expressions in Macao’s Portuguese Creole. Macao: Macao Special Administrative Region.