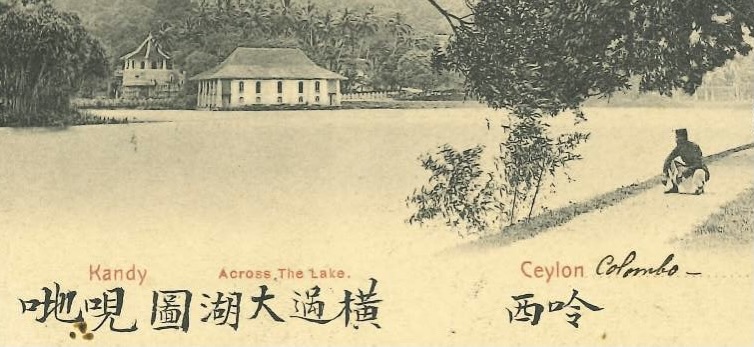

In 2017, milk tea was declared as an item of “intangible cultural heritage” of Hong Kong. Hong Kong-style milk tea (港式奶茶 gong2 sik1 naai5 caa4) is a tea drink originated in restaurants called bing sutt (冰室 Cantonese: bing1 sat1) and cha chaan teng (茶餐廳 Cantonese: caa4 caan1 teng1) where local people like to go to have indigenized western foods and beverages. Other popular beverages include lemon tea (tea served with slides of lemon) and yuen yeung 鴛鴦 (Cantonese: jyun1 joeng1; black tea mixed with coffee). What these beverages have in common is that they use black tea as base, specifically Ceylon tea or 西冷紅茶 (sai1 laang1 hung4 caa4) in Cantonese. 西冷, or 西呤 as shown on the postcard above, is one of the Chinese names of Ceylon, now Sri Lanka.

In Chinese language records, present-day Sri Lanka used to be called differently in different periods. In the Tang dynasty, it was known as 僧伽羅, Sinhala, which is the main ethnic group and language spoken in Sri Lanka. The names 細蘭 (Cantonese: sai3 laan4; Mandarin: xì lán) and 錫蘭 (Cantonese: sek6 laan4; Mandarin: xí lán) were used to represent Ceylon. The current name 斯里蘭卡 (si1 lei5 laan4 kaa1, i.e., Sri Lanka) has been in use since the independence of the country in 1972. Lying Strategically in the Indian Ocean and possessing a good harbor, Sri Lanka has served as an important maritime trading hub for centuries. In 1505 led by Lourenço de Almeida the Portuguese first visited the island and in 1517 they built a fort in Colombo. The Portuguese called the island Ceilão. The Portuguese controlled the coastal areas until the outbreak of the Dutch-Portuguese War. King Rajasinha II requested aid from the Dutch East India Company to expel the Portuguese. Though the Dutch won and took over Colombo in 1656, they violated the agreement with the King and continued to occupy the areas they captured until 1796. Then came the British occupation in 1815. The island was called Ceylon in English. British Ceylon ended in 1948; and in 1972 the name Sri Lanka, was adopted for the Republic.

While the Portuguese and Dutch were competing for spices in Ceylon, the British were more interested in tea. Today Ceylon Tea is synonymous with fine tea. For this reason, even though Ceylon is no longer the official name of the country, this historical name continues to be used to stand for high-quality tea products. The other place names on the postcard – Colombo and Kandy – were also important in the history of Ceylon tea industry. Kandy is a major city located in the Central Province. The postcard depicted the city’s attractions – the Kandy Lake and Ulpange or the Queen’s Bathing Pavilion. Kandy was represented as 哋哯 dei6 gin3 (read from right to left) in characters. At this point, you may notice a difference in the direction of which Chinese characters are read, since the characters 西呤 for Ceylon should be read from left to right. As Chinese characters are square-shaped symbols, they can be arranged and read in different directions, for example from left to right, right to left, or top to bottom. If you read the line 圖湖大過橫 on the postcard from right to left, you will see that it was a translation of “Across The Lake.”

James Taylor was the first person to introduce tea as an industry to Ceylon. In 1867, he established a tea plantation in Loolecondera estate in Kandy. Located at the west coast, Colombo is the most economically robust city of the island. The first Colombo Tea Auction was held in 1883. Teas from different estates would be transported to Colombo for auction. Since then, Ceylon has become a major tea producer and exporter of the world. While in the 1880s, Ceylon tea was still a new brand in the British market, by the 1890s it had occupied the third place, after India and China, in British tea consumption.1

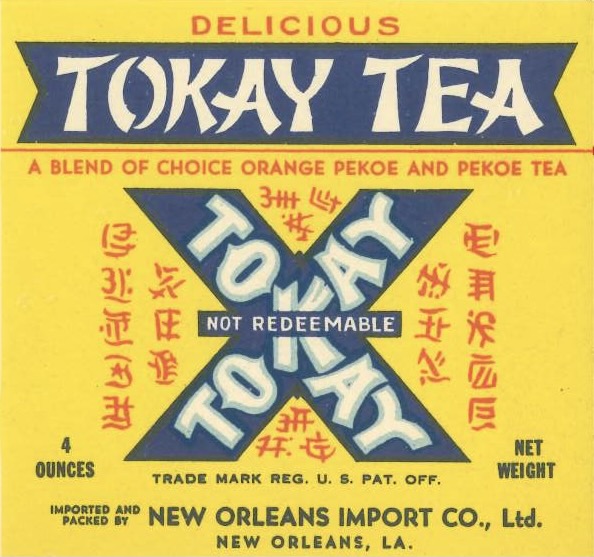

Black tea produced in South Asia adopts a grading system that bases on the appearance and size of tea leaf. Western tea traders use specific terms to classify tea, for example “Orange Pekoe” designates the class of tea composed of new whole-leaves without tips. The word pekoe is believed to come from Chinese 白毫 ‘white hair,’ pronounced as pe̍h hô in Min Nan, baak1 hou4 in Cantonese, and bái háo in Mandarin. In China, Pokoe refers to the white downy hairs covering the tea leaves. The Oxford English Dictionary records the first use of Pokoe in 1713. The origin if the “Orange” part in Orange Pekoe is less clear. Some suggest it comes from the Dutch Orange royal family, as China teas were brought to Europe by the Dutch traders.

Black tea is graded according to the wholeness and size of tea leaves. Tea leaves that are crushed are referred to as “broken.” Fannings and dust are the small pieces left after the crushing process. They are usually used for tea bags and they produce a stronger brew. The common abbreviations are shown below.2

Whole-leaf

STGFOP: Special Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe

SFTGFOP: Special Finest Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe

FTGFOP: Finest Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe

TGFOP: Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe

GFOP: Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe

FOP: Flowery Orange Pekoe

OP: Orange Pekoe

Broken

TGFBOP: Tippy Golden Flowery Broken Orange Pekoe

GFBOP: Golden Flowery Broken Orange Pekoe

FBOP: Flowery Broken Orange Pekoe

BOP: Broken Orange Pekoe

BPS: Broken Pekoe Souchong

BP: Broken Pekoe

Fannings

BOPF: Broken Orange Pekoe Fannings

BPF: Broken Pekoe Fannings

PF: Pekoe Fannings

Dust

PD: Pekoe Dust

D: Dust

Tea tasters combine teas of different grades in order to produce the desired aroma and texture. This process is called tea blending. For example, English Breakfast is a blend of teas from Assam, Ceylon, and Kenya. The tea base of Hong Kong-style milk tea typically comprises Broken Orange Pekoe (30%), BOP Fannings (30%), and Dust (30%). The last 10% comes from Lipton tea.3

1. Walsh, Joseph M. 1892. Tea, Its History and Mystery (Illustrated). Philadelphia: The author.

2. Ukers, William H. 1935. All About Tea. Vol. 1. New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Company.

3. “How Hong Kong-style milk tea became part of local culture” South China Morning Post. 9 Nov, 2017. https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/food-drink/article/2119111/how-hong-kong-style-milk-tea-became-part-local-culture