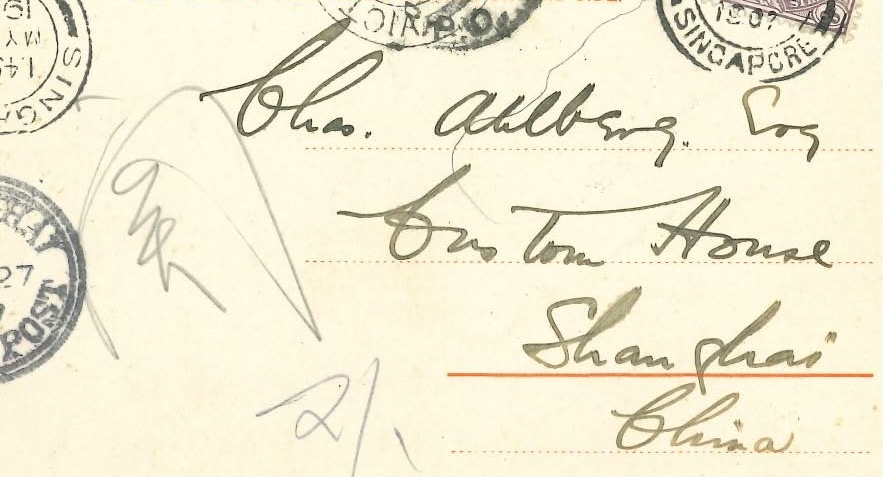

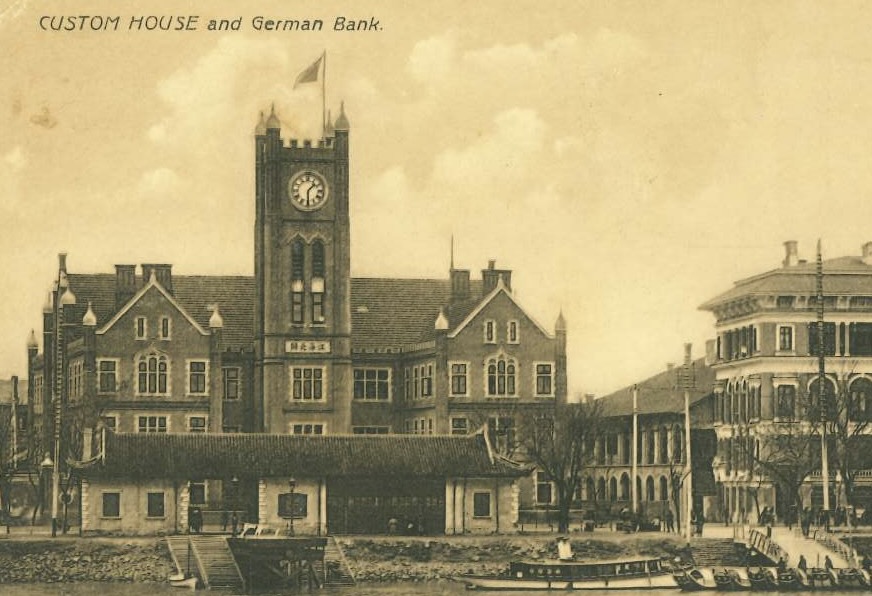

The postcard above was sent in 1907 from Singapore to the Custom House of Shanghai via Hong Kong. The Custom House, called 江海北關 in Chinese, in operation at that time was a red-brick building facing the Huangpu River. Completed in 1893 and located at the Bund (外灘), the centre of European powers, this western architecture had a clock tower in the middle and two wings at both sides. It was demolished in 1925 and a new Custom House was erected at the same location in 1927. Like present-day Customs, the main functions of the Custom House included imports and exports clearance, collection of customs duties, and controlling border security.

Before Shanghai became the main trading port, foreign trade was centred in Canton city. Another term for custom house was chop-house. A chop-house was an office where foreign ships obtain chops ‘stamp, permit’ to upload or unload goods. William C. Hunter, an American, described the functions of the chop-house in Canton as follows.1

“On the edge of the river, facing the ‘Pow Shun’ and the Creek Hongs were ‘Chop’ houses, or branches of the Hoppo’s department, whose duty it was to prevent smuggling, but whose interest it was to aid and facilitate the shipping of silks (or the landing of clothes) at a considerable reduction from the Imperial tariff.”

The quotation mentioned the name Hoppo. Some suggested that the word was based on a department called 戶部 (Board of Revenue) (wu6 bou6 in Cantonese; hùbù in Mandarin) of the Chinese government. Herbert Allen Giles (1845–1935), British diplomat and sinologist, proposed this as one of the two possible origins of Hoppo. He stated that:2

“The Haikwan (q.v.) or Superintendent of Customs at Canton, has been so called for many years. The term is said (1) to be a corruption of Hoo poo 戶部 – the Board of Revenue, with which office of Hoppo, as collector of duties, is in direct communication; (2) to be from Ho pok 河泊 [originally] “god of the rivers” but subsequently applied to the Canton river-police magistrate. A well-known native work, however, states that 關部 the Superintendendent of Customs is called in English 合煲 Hoppo.”

Since the Hoppo was a high-ranking officer, foreign traders could not contact or meet him directly, all communications must be channeled through the Hong merchants. Hunter (1882) explained the situation and commented on the origin of the name Hoppo.

“The Hong merchants were responsible to the Hoppo for the duties on all exports and imports. They alone transacted business with that officer’s department—viz., the ‘Customs’—by which foreigners were spared trouble and inconvenience. It may be as well to mention here that the ‘Hoppo’ (as he was incorrectly styled) filled an office especially created for the foreign trade at Canton. He received his appointment from the Emperor himself, and took rank with the first officers of the province. The Board of Revenue is in Chinese “Hoo-poo,” and the office was locally misapplied to the officer in question.”

The following interaction took place in Canton between Commodore Hugh Lindsay of the East India Company and Mowqua, one of the richest Hong merchants in Canton. Since Commodore Lindsay’s fleet was prohibited from sailing, he decided to petition the Hoppo personally. Mowqua tried to stop the Commodore from proceeding and told him he would take care of the matter. The reasons given by Mowqua was as follows.3

Ah! mister commodore, what for you come here?

you wanty security merchants have cutty head?

Hoppo truly too much angry English come him house, he will cutty my poor old head

Good mister commodore, me takey petition, and truly will get answer directly.

What you come here? you wanty see Hoppo? That no can do.

Let’s take a closer look at the speech of Mowqua which was conducted in Pidgin English. A Hong merchant was also known as a security merchant. Questions in Pidgin English generally started with the question word what. For instance, to ask ‘why’–questions, what for was used instead of why. Mowqua was very concerned about “cutty head” which was a form of execution. The phrase too much could mean ‘too, a lot, very’ depending on what followed. Truly could be used to show emphasis, as in Hoppo truly too much angry and truly will get answer directly. Since the copula verb to be convey little content meaning, it should not surprise you that it was omitted in several places. As mentioned before, verbs appeared in bare form in Pidgin so that there were not marked for tense. Overt indication of tense, as in will cutty and will get, was unusual. There were also different forms of reduction at the sentence level. When sentences are combined, they may indicate what are called coordination or subordination in English grammar. Unlike standard English, Pidgin English generally did not use conjunctions such as and, but, because, when etc. to explicitly link sentences. For instance, that or because was missing in Hoppo truly too much angry English come him house. In the example you wanty see Hoppo, the infinitive to was absent so that the verbs of the two clauses were placed side by side. This type of structure is indeed very common in Cantonese. The Cantonese sentence below shares the same structure as the pidgin example.

我想見Hoppo

I-want-see-Hoppo ‘I want to see the Hoppo’

Finally, the affirmative can do and the negative no can do obviously expressed (in)ability or (im)possibility.

1 Hunter, William C. 1882. The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days 1825–1844. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co.

2 Giles, Herbert. A. 1886. A Glossary of Reference on Subjects Connected with the Far East (second edition). Hongkong: Messrs. Lane, Crawford & Co.

3 Lindsay, Hugh. 1840. An adventure in China. In Robert, James, John, and Hugh Lindsay. Oriental Miscellanies; Comprising Anecdotes of an Indian Life. Wigan: C. S. Simms.