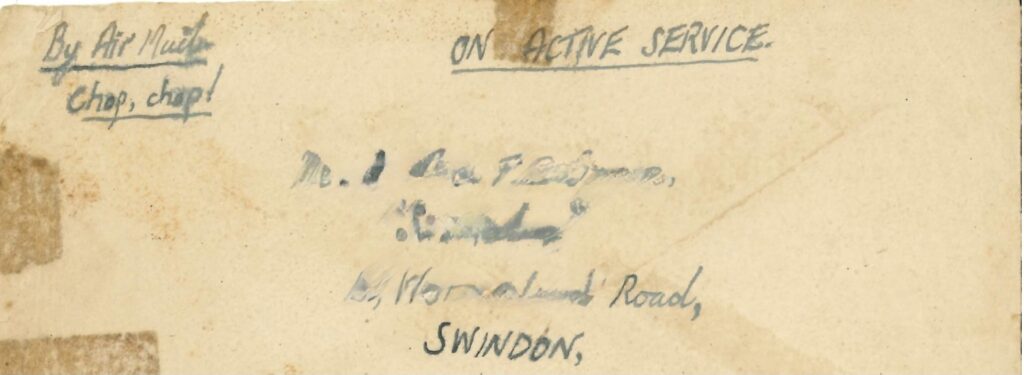

The featured envelope above was sent by someone on active service, in other words, someone who participated in military action as a member of the armed forces. The cancellation was dated in August 1946, nearly one year after the end of the Second World War. Although the letter was missing, the message must be urgent, as the writer also added the note “Chop, chop!” to the cover. Originally used in Chinese Pidgin English, chop, chop, meaning ‘quick,’ was spread to some English-speaking countries like Britain and America. Bear in mind that the origin and meaning of chop, chop (in duplicated form) are unrelated to chop meaning ‘a seal’ or ‘brand.’

How did chop, chop enter the English lexicon? To explain this, we have to understand how Chinese Pidgin English came into being first. The word pidgin is believed to be representing how Chinese pronounced the English word business. A pidgin language is created under circumstances where two or more groups of people speaking different native languages are in contact, The resulting pidgin language serves as a lingua franca to allow cross-cultural communication. The context in which Chinese Pidgin English emerged was trade. The Portuguese were the first European traders to arrive on Chinese soil in the 16th century. Granted settlement in Macau in 1557, the Portuguese established themselves as pioneer intermediaries in the early days of China-West interactions. By the 18th century, besides the Portuguese, there were traders from Britain, France, Sweden, Holland, and so on. Among these Westerners, the British were the most ambitious and aggressive. In order to better regulate the activities and movement of the Europeans, the Chinese government restricted foreigners’ commercial activities and dwellings within an area known as “Thirteen Factories” located in the southwest of Canton 廣gwong2州zau1 (now Guangzhou). This location is also the origin of Chinese Pidgin English, also called Canton English at the time. Regular contact between the Chinese and Westerners in Canton promoted the emergence of Chinese Pidgin English, which served as a lingua franca for people not sharing a native language. An anecdote about this means of communication is given below. Visiting the Ling-nam, the area covering mainly Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan known as 嶺ling5南naam4 in Chinese, Benjamin Couch Henry recalls how people communicate in Chinese Pidgin English as follows (Henry 1886: 26).1

My wantchee you catchee chow-chow chop-chop

Man-man my waitee dat coolie come back, he belong one piece fulo man too muchee chin-chin joss

On another occasion, Henry hears an exchange in a silk (sillik) shop like this. The Chinese shopkeeper says:

More better you cum shaw my one piece, sillik numba one look see

The customer wants a discount but because the silk is of top quality, the shopkeeper thinks he will lose too much profit. So, he replies:

No can my makee too muchee losee, you no likee, maskee, my chin-chin you come back.

The name Chinese Pidgin English indicates two main types of participants and languages in the creation of the language – Chinese, especially Cantonese and English. Let’s use the short text above to understand how Chinese Pidgin English works. There are four reduplicated forms: chow-chow, chop-chop, man-man, and chin-chin; all are of or allegedly of Chinese origin.As shown in the featured envelope above, chop-chop means ‘quick(ly).’ Chin-chin, derived from 請, pronounced cing2 in Cantonese and qǐng in Mandarin, can be used as a salutation, as well as a verb meaning ‘invite, request, worship’ such as chin-chin joss ‘worship god’ and my chin-chin you come back ‘I beg/invite/welcome you to come back.’ Chow-chow can refer to ‘food,’ ‘to eat,’ or ‘mixed’ depending on the context in which it appears. Man-man is derived from 慢慢 ‘slowly,’ pronounced maan6 maan6 in Cantonese and màn màn in Mandarin. Cum shaw means ‘patronize’ here and is derived from 感謝 ‘to thank, to be grateful’ pronounced kám-siā in Hokkien spoken in the Fujian province of China. The earliest European settlers in China – the Portuguese also left their traces in Chinese Pidgin English. The origin of the word joss is Portuguese deus ‘God’ and maskee often means ‘never mind’ and is believed to be related to mas que. So, while the lexicon of Chinese Pidgin English is predominately English, other languages such as Chinese and Portuguese also play a role.

The grammar of Chinese Pidgin English, though co-constructed by Cantonese and English, is not a replication of the two languages. The first feature you may notice is the use of my as subject and object pronouns. The invariance of subject and object form could be attributed to a characteristic found in Cantonese, but why the possessive form is chosen is still a puzzle. The definite and indefinite articles in English are represented differently in the pidgin text. Rather than using the and a,they are expressed as dat (from that)in dat coolie ‘the coolie’ and one in one piece fulo man ‘a foolish man.’ As a general rule, the copula verb to be is not used in Chinese Pidgin English. So when it comes to a need to indicate connections expressed by to be, the word belong takes its place.

Rooted in Canton, Chinese Pidgin English radiated to other ports like Shanghai and Hong Kong. After the two Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860), significant political and economic changes occurred in China – foreign trade was no longer confined to Canton, the entire China was opened up; and Hong Kong became a British colony. The implication for Chinese Pidgin English was that it found new soil to grow, namely Shanghai and Hong Kong, both emerging as international commercial hubs and cosmopolitans after the wars. Martin Booth, son of a civil servant, followed his family to move to Hong Kong in 1952. A seven-year-old boy at the time. Booth spent his childhood trying to understand every aspect of Hong Kong, including the languages spoken there. Chinese Pidgin English was not strange to him because this was the common language between him and the Chinese domestic servants. He remembers how he was taught to treat the domestic servants: “It was impressed upon me that I should never make unreasonable demands of Wong or Ah Shun and I was never to say Fide! Fide! or Chop! Chop! (Quick! Quick!) at him.”2 (Booth 2005: 150) Fide is a representation of Cantonese 快faai3啲di1.

While 快faai3啲di1 is the semantic equivalent of chop, chop, and is the most frequently used, some other expressions in Cantonese that also denote ‘quick,’ all involve reduplication. These expressions are 急gap1急gap1, 速cuk1速cuk1, and 匆cung1匆cung1, as shown in the following sentences.

你nei1做zou6咩me1急gap1急gap1腳goek3咁gam2走zou2?

You-do-what-quick-quick-foot-like that-run

‘Why did you leave in such a hurry?’

速cuk1速cuk1磅bong6,唔m4好hou2兩loeng5頭tau4望mong6 。

Quick-quick-pay-not-good-two-head-look

‘Pay the money quickly. Don’t look around.’

佢keoi5成sing4日jat6都dou1來loi4去heoi3匆cung1匆cung1。

(s)he-always-also-go-come-quick-quick

‘(S)he is always in a hurry.’

Unlike 快faai3啲di1, the uses of these reduplicated forms are quite restrictive. 急gap1急gap1腳goek3, for example, is usually used in the context of physical movement. 磅bong6 is a shortened form of 磅bong6水seoi2, a slang for ‘paying money.’ The last expression 匆cung1匆cung1 is often used to denote a brief time.

1. Henry, Benjamin Couch. 1886. Ling-Nam or Interior views of southern China. London: S. W. Partridge and Co.

2. Booth, Martin. 2004. Gweilo: Memories of a Hong Kong Childhood. London: Doubleday.