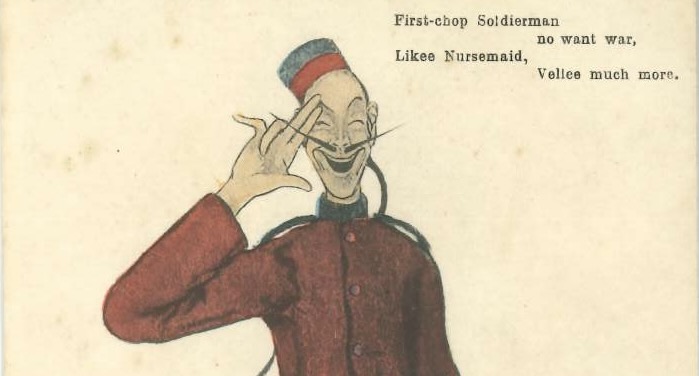

When a foreign word takes root in new soil, the life of the word takes its course and continues to evolve in the new environment. The word chop is a good example. Etymologically related to Hindi and Malay, chop as used in Chinese Pidgin English not only shows traces of its sources but also expands on them. In the last blog post, several meanings of chop have been introduced – a seal, a mark, a trademark, or a document. The word expands its use when combined with other words such as chop-boat ‘a boat for carrying goods’ and chop-house ‘custom house.’ The featured postcard of the early 20th century gives a further use of chop, namely first chop. Before explaining what first chop means, let’s read the whole verse first.

First-chop Soldierman

no want war,

Likee Nursemaid,

Vellee much more.

The postcard depicts a soldier wearing a queue, a typical male hairstyle of Qing China, and dressed in a western soldier’s uniform. The language of the verse also demonstrates a combination of eastern and western linguistic elements. The form and structure of the language resemble what is known today as Chinese Pidgin English, or “pidgin English” or “Canton English at the time it was spoken. A pidgin is a language that emerges from a need for people speaking different first languages to have a lingua franca to enable effective communication. For various reasons, these people maintain constant contact and use the pidgin they created as a lingua franca. The resulting pidgin demonstrates linguistic features drawing from two or more languages. The context in which Chinese Pidgin English emerged was trade between China and the West. Multilateral trade in China began in the 18th century and took place in a designated area located in the southwest of Canton (now Guangzhou), China. The word pidgin is believed to be the Chinese way of pronouncing the English word business, so Chinese Pidgin English began as a business language.

Returning to the verse, the phrase first chop is usually applied to valuable goods like silk and tea but can also be seen in descriptions like first-chop man and first-chop soldierman. First chop is equivalent to “first-rate, first-class” in today’s language. There are other features in the verse that are also characteristic of Chinese Pidgin English. Placing the negation marker no directly before the element being negated as in no want war is an example. Chinese Pidgin English is a practical language, meaning communication between Chinese and foreigners emphasizes economy and conciseness. This has a direct consequence on the structure of the language. Content information is more important and hence expressed more explicitly than grammatical information which can be inferred from the discourse context. For example, the subject and/or object can also be omitted when the context can supply the referents. The verse above exhibits this feature. The spelling of likee and vellee also captures some phonological features of Chinese Pidgin English. The –ee in likee indicates an extra vowel is intended, making it a disyllabic instead of a monosyllabic word. The -ll- in vellee replaces the sound /r/, which does not exist in Cantonese.

As businesspeople, traders need to ensure that the commodities they purchase are worth the value. As an expert in China trade and a long-term resident in Canton, William C. Hunter describes how cargoes are classified according to the qualities of the goods in the 19th century. A cargo labelled as ‘first chop’ means it is of the best quality. As the number increases to like No. 6, 8, or 10 chop the quality decreases accordingly.1 Besides using numbers, the brand names can also reflect the qualities of goods. For silk, Ernest O. Hauer describes the qualities of different brands of silk as follows.2 Godowns are warehouses. Like chop, godown also has an Indian origin. “The compradores (to return to the silk racket) would see to it that the noble commodity would reach Shanghai in due time, would be stored in the company’s godowns, and would be graded according to its quality, to leave Shanghai for Europe or America as “Factory chop,” “Double Eagle chop,” “Three Dancers chop,” “Triton chop,” or “Inferior chop.””

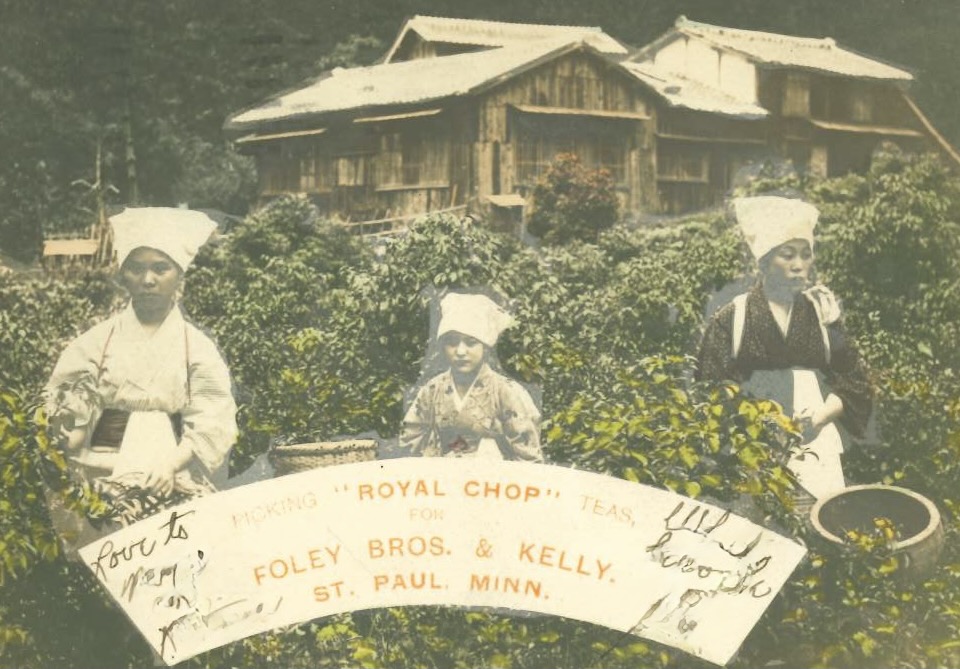

The postcard on the right shows some Japanese women picking tea leaves for a brand of tea called “Royal Chop.” When used as part of a brand or trade name, chop/cap usually occurs before the names, as in Cap Tabik, Chop Rimau, or Chop Ban Hin Lee in the Straits.However, the tea brand Royal Chop has a different structure. The difference in the position of chop/cap tells us a fact in languages in contact, which is, that influence from different languages may produce different linguistic outcomes. The brands from the Straits follow Malay grammar, whereas Royal Chop adopts the structure of English noun phrases.

Another way to express ‘the best’ in Chinese Pidgin English is number one or No. 1. The following is a dialogue between a Chinese tailor and a European in the 1830s. Upon seeing the European, the tailor welcomes him.3

Tailor: Yes, sir; you have got make some pigeon with me? Me glad see you—me make all true pigeon.

What thing you suppose you wantshey?

The European customer wants some grass-cloth jackets and pongee pantaloons, so the tailor shows him what he has got.

Tailor: Have got—have got—suppose you wantshey lookey, muster.

This grass-cloth good thing—number one, first chop—wantshey?

When reading Chinese Pidgin English texts, we should bear in mind that, unlike English and Cantonese which are well-established languages, a greater degree of variation does exist in Chinese Pidgin English. This is because as long as the variations do not affect understanding speakers of the pidgin are more tolerant to interspeaker variations. Writing the pidgin is a case in point. There is no standard way to write the language. Therefore, authors may spell words differently depending on their abilities to transcribe speech into writing. A clear example is pigeon and pidgin. When the tailor says make all true pigeon, hedoes not mean the bird pigeon but pidgin meaning ‘business.’ In other words, pigeon and pidgin are orthographic alternatives to the same word. Another spelling variation is the representation of the extra vowels occurring in some words. Compare the form –ee as in likee in the pidgin English verse and -ey like wantshey and lookey in the dialogue. There are also examples of lexical variation. Several forms are recorded as first-person pronouns: while many sources show my but me and I are also attested. The word muster ‘a pattern, a sample’ is derived from Portuguese mostra, meaning ‘an exhibition, a display.’ The tailor uses number one and first chop somewhat interchangeably to praise his product. Both expressions are used descriptively to indicate a superb kind.

Language is not static. No matter whether a word is of native or foreign origin, when it continues to exist in a language, its life is always evolving, adapting to the changing environment. This is what we see in the uses of chop.

1. Hunter, William C. 1882. The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days 1825–1844. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co.

2. Hauser, Ernest O. 1940. Shanghai: City for Sale. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

3. Ruschenberger, W. S. W. 1838. Narrative of a voyage round the world, during the years 1835, 36, and 37. London: Richard Bentley.