Kopi is a popular beverage in Singapore and Malaysia. On menus of restaurants, you will find that it can be mixed with other ingredients like milk, sugar, teh ‘tea’, and peng ‘ice’ in different ways. One way to drink kopi is shown in the featured coffee sachet above – “Kopi-O” Kosong. Kopi is the Malay word for ‘coffee’; O is a Hokkien word (Hokkien 福fuk1建gin6話waa2 is one of the main Chinese languages spoken in Southeast Asia) meaning 烏 ‘black’, and kosong meaning ‘zero, empty’is another Malay word. So, if you order Kopi-O Kosong, you’ll get a black coffee, without milk and sugar. A Malay word that has a lasting impact not only in the Straits but also in China is cap as in the brand name of the coffee Cap Tabik ‘brand salute.’ Cap is the current spelling, but before the Joint Rumi Spelling (Ejaan Rumi Bersama) of 1972, it was spelt chap. Before we look at how chap/cap landed in a foreign land, we have to look at its meaning in Malay. In Clifford and Swettenham’s A Dictionary of the Malay Language: Malay-English (1894: 324), chap is defined as “A ‘chop,’ a seal; the seals used by Malays of rank in lieu of signatures, and which are more respected than letters which are merely signed; letters bearing seals; the letters from a Malay Râja; to print, to engrave, to lithograph.”1 The A Malay-English Dictionary (1901: 256) gives similar meanings to chap but in addition, it also mentions the Hindustani word chhap.2 Based on these explanations, we see three forms: chap, chop, and chhap. So what are their connections?

Yule and Burnell’s Hobson-Jobson (1886) dictionary contains thousands of “Anglo-Indian” words, that is, words in English that have an Indian origin. One such word is chop, which they defineas “a seal-impression, stamp, or brand.” The word originates from Hindustani chhāp, eventually adapted into Malay as chap and later cap.3At some point, chhāp/chap was brought to China and took the form chop in Chinese Pidgin English.We may never know when the word was first used in China but its beginning was likely related to trade. Soon after the landing of Vasco da Gama in India in 1948, which opened up the sea route to the East, the Portuguese established various factories or trading posts in India. In 1511, the Portuguese also occupied Malacca. In China, the Portuguese were permitted to settle in Macau, located at the mouth of the Pearl River estuary of the Guangdong province, in 1557. Following the Portuguese, other Europeans, particularly the English, began to explore the Chinese market too. Already secured its domination in India, the English East India Company eventually also gained permission to trade in China. This started a long-lasting network of trade between India and China. Canton (now Guangzhou) soon became an international commercial and cultural hub because it was the only place where Westerners could trade and dwell. However, a problem that the international community needed to resolve was communication. A resolution to the circumstance was to create a new language that comprised linguistic elements from English and Cantonese (the primary language spoken in Canton). The language is known today as Chinese Pidgin English, which served as a lingua franca to allow the Chinese and Westerners to communicate.

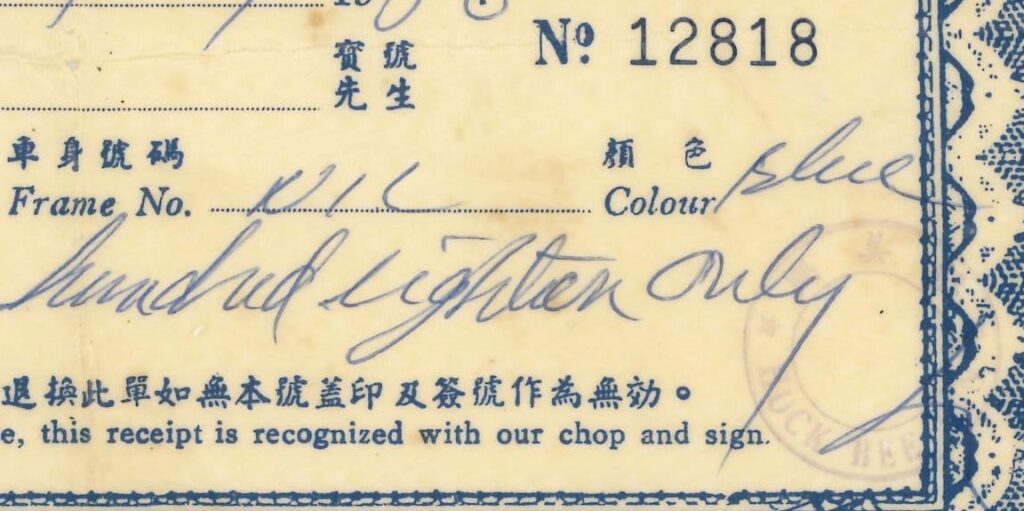

As in Hindi and Malay, chop in Chinese Pidgin English refers to a ‘seal’ or ‘stamp’. Each chop is unique and serves the function of identification for a person or a company. The receipt on the left-hand side has a line at the bottom that reads: “…this receipt is recognized with our chop and sign.” This example further shows that a chop denotes agreement and authority. The following dialogue shows that Canton was as multicultural as today’s international city and the medium of interaction was “Canton-English” or Chinese Pidgin English. The dialogue is between a European customer and a Chinese shopkeeper. The dialogue is about the European’s last purchase in the shop.4

European: Before time, I have see one small boy stay this shop; he have go country?

Chinese: He catchee chowchow; come one hour so; you wantchee see he?

European: Maskee; you have alla same; before time my have catchee one lucker-ware box, that boy have sendee go my house, no have sendee one chop?

Chinese: Sitop litty time; I sendee call-um he come.

As you can see, the language is different from English even though the words are predominantly English. The language was used by Chinese and Westerners alike if the need arose. English no doubt participated in the development of the language; however, Cantonese also played a pivotal role. So, let’s see how Chinese Pidgin English works. Definite and indefinite articles are represented differently in Chinese Pidgin English. While that (that boy) is used in place of the definite article the, in this dialogue we can see that, apart from the numeral ‘one’, one is also used as the indefinite article a, like one small boy and one lucker-ware (lacquerware) box. Chowchow means ‘food’. Maskee expresses ‘never mind’. One chop here may refer to ‘a receipt bearing a seal’. Pronoun is another area that deserves attention. The different instances of he show that there is no difference between the subject and object forms. The first person pronoun I and my coexist but the latter form is more common. Compared with Cantonese and English, Chinese Pidgin English has a much reduced lexicon but this does not necessarily mean that it lacks expressive power, as different ways can be deployed to compensate for the lexical reduction. A common way used by many languages is to combine existing words to create new meanings, for before time means ‘previously, last time’ and sitop (stop) litty time means ‘wait for a while.’ Although most of the words are from English, some of them have an extra -ee ending, notably catchee, sendee, talkee, makee, and walkee. Other words may have different endings like alla and callum.

During the First Opium War (1939–1842), China prohibited the importation of opium. Hence, the extract below shows a Chinese official informing the captain of a foreign ship to leave China.5

That Emperor send chop makee strong talkee, must drive away all ship, my chin, chin you, Mr. Captain; katchee anchor, makee walkee, my can talkee that Ison Tuck (Viceroy) all ships have go away!

Although most words in Chinese Pidgin English are derived from English, the presence of other languages is also evident. For example, chop comes from Malay chap and Hindi chhap. In the example above, chop refers to a decree or an official document, bearing the seal of the Emperor or a high official. Chin chin ‘ask’ is derived from Chinese 請cing2. In place of the definite article the, Chinese Pidgin English uses that as inThat Emperor. The subject can be omitted when its referent can be inferred from the context, which is also the case in Cantonese. Grammatical information such as tense and number tend not to be marked on verbs and nouns. Given its small lexicon, some words like talkee can express multiple related meanings. The first occurrence of talkee means a ‘statement, announcement’ and the second means ‘talk to, tell’.

Like products, shops can also be branded. In Giles’s Glossary (1886: 42), chop is translated into Chinese as 號hou6 or 字zi6號hou6, which means a ‘mark, name, business house.’6 Many traditional Chinese shops bear the character 號 as part of their names like the photo on the left/right. Chop Lum Seng (the Chinese name 南成號 should be read from right to left according to traditional writing practice) is a grocery located in Penang. This use of chop in the Straits probably began in the late 19th century when a large number of Chinese immigrants arrived there. Among these immigrants was Yeap Chor Ee (1867-1952), a barber turned banker, who arrived in Penang in 1885 and established his first shop called Chop Ban Hin Lee (萬興利 in Chinese) in 1890 (Yeap 2019: 62).7

Traders in the Far East would be familiar with the term chop dollar. Jonas D. Vaughan, an official and a lawyer in colonial Singapore, describes the use of chopped dollar in the Straits as follows: “Every Chinese merchant in those days put his Chop on every good dollar that passed through his hands, and the consequence was that dollars got so fearfully marked that they soon lost all traces of any design, dates or figures. Unless chopped a dollar would not be received in payment. In the Straits chopped dollars were some years ago considered the best but now they are refused, and are below par in value.”8 Chop marks, sometimes recognizable as Chinese characters, were stamped onto silver coins in order to attest to the genuineness and composition of the coins.

1. Clifford, Hugh, and Frank Athelstane Swettenham. 1894. A Dictionary of the Malay Language: Malay-English. Taiping, Perak: The Government Printing Office.

2. Wilkinson, Richard James. 1901. A Malay-English Dictionary. Singapore: Kelly & Walsh, Limited.

3. Yule, Henry, and Arthur Coke Burnell. 1886. Hobson-Jobson Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms. London: John Murray.

4. Anonymous. 1836. “Jargon spoken at Canton; how it originated and has grown into use; mode in which the Chinese learn English; examples of the language in common use between foreigners and Chinese”, in Chinese Repository 4:428-35.

5. Bingham, J. Elliot. 1842. Narrative of the expedition to China: from the commencement of the war to the present period, with sketches of the manners and customs of that singular and hitherto almost unknown country. London: Henry Colburn.

6. Giles, Herbert A. 1886. A Glossary of Reference on Subjects Connected with the Far East. (second edition). Hongkong: Messrs. Lane Crawford & Co.

7. Yeap, Daryl. 2019. The King’s Chinese. Selangor: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre.

8. Vaughan, Jonas Danial. 1879. The Manners and Customs of the Chinese of the Straits Settlements. Singapore: The Mission Press.