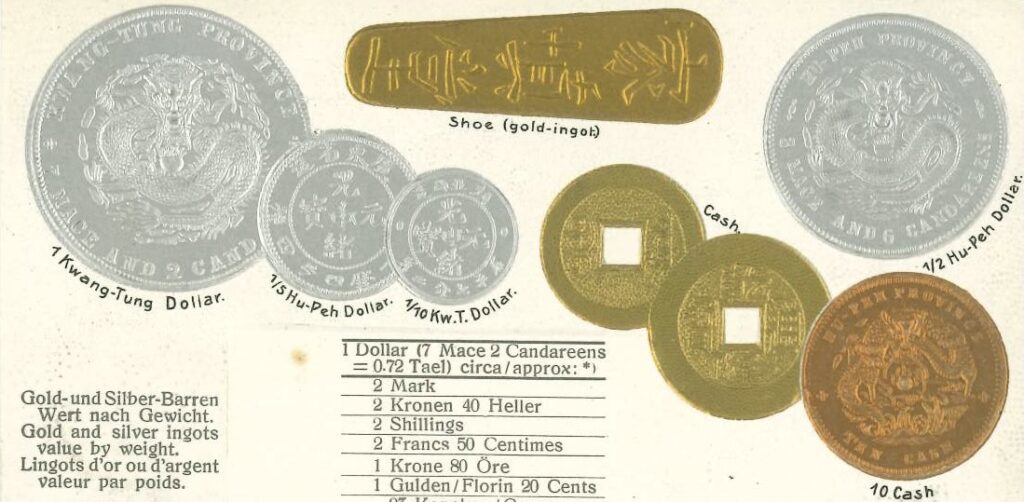

Before taking a vacation to explore a different culture, one thing we do is check the exchange rates between the local and foreign currencies. Today, it takes seconds to know the best rates with an application or on the internet. But do you know how this information was disseminated one hundred years ago? One way was through postcards like the one featured above. On such postcards, you can see images of coins used in another country, in this case, the coins of the Kwang-Tung (Guangdong) province and Hu-Peh (Hubei) province of China. Below the images is a table showing the equivalents between different currencies for the users’ reference. Besides recognizing the coins, visitors should also know the names of the denominations. The featured postcard contains some old names: tael, candareen (also spelt candarin), and mace. These names are already obsolete as denominations of currency but in Hong Kong, they are still used as units of weight alongside the decimal system. Tael, candareen, and mace are neither of Chinese nor English origin, the Hobson-Jobson (1886) dictionary attributes their origin to Malay.1 The following shows their source words and corresponding names in Cantonese.

| Source | Cantonese | |

| tael | taïl or tahil (Malay) | 兩loeng2 |

| candareen | kandūri (Malay) | 錢cin4 |

| mace | mās (Malay | 分fan1 |

| cash | kāsu (Tamil); Portuguese caixa | 厘lei1/4 |

In the late 19th century, one dollar (or 圓jyun4 in Chinese) was equivalent to seven mace and two candareens which was about 0.72 tael. 0.72 tael was approximately two shillings, two Frances and 50 Centimes, or 48 cents (USA). One tael was divided into ten mace; one mace into ten candareens; and one candareen into ten cash. In other words, one tael equaled 1000 cash. At this point, we see another denomination: cash, which is derived from Tamil kāsu but the Portuguese form caixa could also be a source.

Another piece of information from the postcard is different types of tael. While tael was used in the market, Haikwan tael (海hoi2關kwan1兩loeng2) designed a uniform unit for paying customs duties. Haikwan was a transliteration of 海關 ‘customs’, i.e., the Imperial Maritime Customs of the Qing government. 100 dollars (pesos) was about 72 Haikwan taels. As a weight unit, one Haikwan tael was equivalent to 590,35 grains of pure silver at the time of the postcard. The flag at the bottom left of the postcard was the flag of the China Merchants Steam Navigation Company (輪船招商局). The company was established in 1872 and founded by Li Hongzhang (李鴻章). It was renamed China Merchants Group (招商局集團) in 1985 and the current head office is in Hong Kong.

Whether tael, candareen, mace, or cash, coins were made of metal and were often alloyed with copper or lead. Therefore, shroffs were needed to guarantee the money received was of the purest type. Shroffs were specialists in distinguishing genuine money from counterfeit and determining their values. While serving as the British Consul in Ningpo, Robert Thom sent a notice in 1844 reminding the British merchants of the appointment of three shroff-shops to receive duties from foreign merchants. The shroff-shops mentioned in Thom’s notice were: 2

1st. The ( ) Kew-au shroff-shop, of which the responsible person is ( ) Yé-Kin-hung, in Government employ.

2nd. The ( ) Yuen-Ho shroff-shop, of which the responsible person is ( ) Chung-Kwang-Keen, having the literary title of a Sang-yuen.)

3rd. The ( ) Ken-ho shroff-shop, of which the responsible person is ( ) Ching-Suy-tan, in Government employ.

The calculation of duties was given as: “Duties will be received in pure Sycee silver 98 to 100 touch custom-house weight, with the addition of one tael two mace per hundred taels (1t.2m.p. 100 T.), expenses for remelting, as at Canton; or if the duties be paid in foreign money, the said foreign money will be put through the crucible, and taken for just so much pure silver as it yields, with the addition of 1t.2m.p.100 taels for remelting as above.”

Here, we see another monetary unit: sycee. Sycee is silver or gold ingots of various shapes and sizes used in imperial China. Robert Thom’s notice mentions the term shroff-shop.This usage refers to an establishment or office where payments were collected. It was probably an antecedent of “shroff office” or simply “shroff” as used to mean a cashier office which is still seen in Hong Kong.

Like today’s commercial centres, different foreign currencies were circulated in 19th-century trading ports like Canton, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. Foreign monetary terminologies may also be adopted due to regular commercial interactions. One of the channels through which the Malay terms entered China was the Portuguese. The Portuguese control Malacca from 1511–1641. In 1557, they gained permission from the Chinese government to settle in Macau. As a result, tael, candareen, and mace could have been imported into China via the Portuguese. The peso was the monetary unit of several former Spanish colonies in the Americas and the Philippines. The Spanish invaded the Aztec Empire of Mexico between 1519 and 1521 for precious metals like gold and silver. From the 17th to the 18th century, hundreds of Galleon ships travelled between Mexico and Asia. Setting off at Acapulco of Mexico, Spanish traders sailed to Manila, where they bought Chinaware and other trade goods from the Chinese merchants. This was known as the Galleon trade which introduced the Mexican dollars to China. In the book The Chinese and English Instructor 《英語集全》(1862), we can glimpse the different currencies used in Canton.3

(C: customer; S: shopkeeper)

C: what time makee pay you send my billee my give you money

‘You send the bill to me in due time and I will pay you’

S: I thinkee you pay my Mexican dollar

‘Please pay me in Mexican dollars’

C: no, my pay you Englishee money

‘No, I will pay you in Sterling money’

S: I losee too muchee discount

‘I lose too much by the discount’

C: so fashion my pay you one half Mexican dollar

‘Well I will pay you one half in Mexican dollars’

one half Englishee money

‘And one half in Sterling’

Chinese called the Mexican silver dollar 鷹jing1銀ngan4 (literally ‘eagle silver’) because of the eagle on one side of the coin. Mexico cast its own coins after declaring independence from Spain in 1821. The dollar was widely used in international trade, including in China, where it became a major currency of trading. The Chinese referred to the “Englishee money” as 紅hung4毛mou4銀ngan4, i.e., ‘red-haired money’. The name 紅hung4毛mou4 initially referred to the Dutch, but it was later generalized to Europeans.

Besides learning the currencies used in China in the 19th century, the dialogue shows the use of a language currently referred to as Chinese Pidgin English. Superficially, the language uses English words but if you read them closely the grammar is different from English. An area where Chinese Pidgin English differs from English significantly is the personal pronoun system. Take first-person pronouns as an example. While English has different forms for the subject (I), object (me), and possessive (my) functions, the possessive form my is used for multiple functions: as subject pronoun as in my give you money, as object pronoun as in I thinkee you pay my Mexican dollar, and as a possessive adjective like you send my billee. Similarly, for the second and third-person, the forms used are you and he respectively. Note that he is used regardless of gender. Chinese Pidgin English emerged as a result of people speaking different languages gathered in Canton (now Guangzhou) in the 18th century for trade. The word pidgin is believed to be the Chinese fashion of pronouncing English business. The comparison of the pronouns in English and pidgin English shows that it is not simply a reduction in forms but also the influence of another language. Chinese Pidgin English was used by both Chinese and Westerners, so apart from English, the local language also contributed significantly. The primary language spoken in Canton, then and now, is Cantonese. The influence of Cantonese and English is evident in the grammar of Chinese Pidgin English. Comparatively speaking, the number of pronouns in Cantonese is fewer than in English. This is because, like Chinese Pidgin English, functionally different pronouns have identical forms, for example, 我ngo5 means ‘I, me, my’,你nei5 ‘you, your,’ and 佢keoi5‘(s)he, him/her, his/her). In Chinese Pidgin English, the form I is occasionally attested.

In Hong Kong, the use of tael, mace, candareen, and cash as denominations of currency has extinct. However, different systems are used for weight measurement: the metric units, Imperial units, and Chinese units. The Malay terms can be seen in the wet markets and shops selling Chinese herbal medicines and gold and silver accessories.

1. Yule, Henry and Arthur Coke Burnell. 1886. Hobson-Jobson Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms. London: John Murray.

2. Accounts and Papers: Thirty-seven Volumes. 7. China. Session 19 January – 23 July 1847. Vol. XL. 1847. “Orders, Ordinances, Rules, and Regulations Concerning the Trade in China. Presented to the House of Commons in pursuance of their Order of January 26, 1847. London: T. R. Harrison. P. 28.

3. Tong, Ting Kü (唐廷樞). 1862. The Chinese and English Instructor 《英語集全》. Canton.