恭gung1喜hei2發faat3財coi4!That’s what the featured image says – 恭喜發財 a wish for prosperity and wealth. The Chinese New Year is the time of the year when families reunite, friends meet, and good wishes are made.

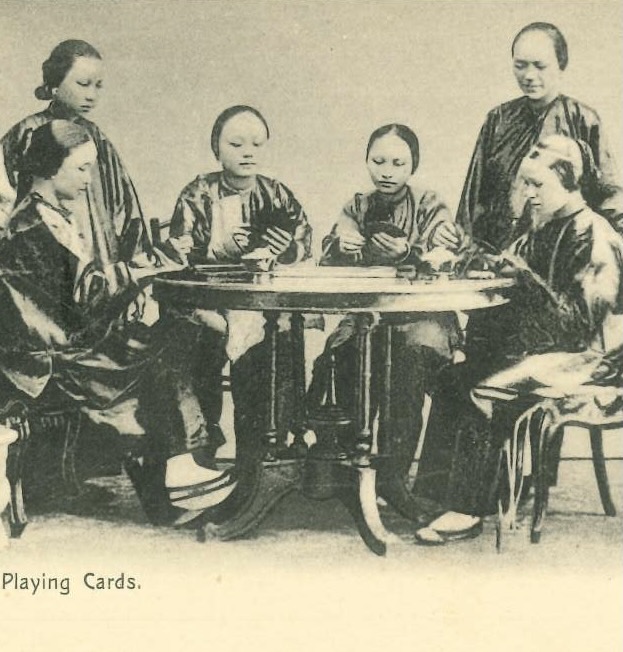

Celebrations for the Chinese New Year begin on the eve of the new year and usually end on the 15th day of the first month, but the first three days of the new year are the most important. The new year is of course the best time to wish for good luck and auspiciousness in the coming year, as well as to ward off back luck. The third day of the new year, 初co1三saam1 in Chinese, is also known as 赤cek3口hau2. It is believed that on this day people would get into arguments or quarrels easily. In order to prevent disharmony traditionally people prefer not to visit relatives and friends. So what do people do to spend the holiday? Some go to temples for chin-chin joss (worshipping gods); some go to the racecourse to place their bet on horse racing; others prefer to have fun at home. Some favourite family games include the mahjong (麻maa4 雀zek2) and card games. However, these games require tools like mahjong tiles or cards, a certain knowledge of the rules of the games, and also usually four players to compete.

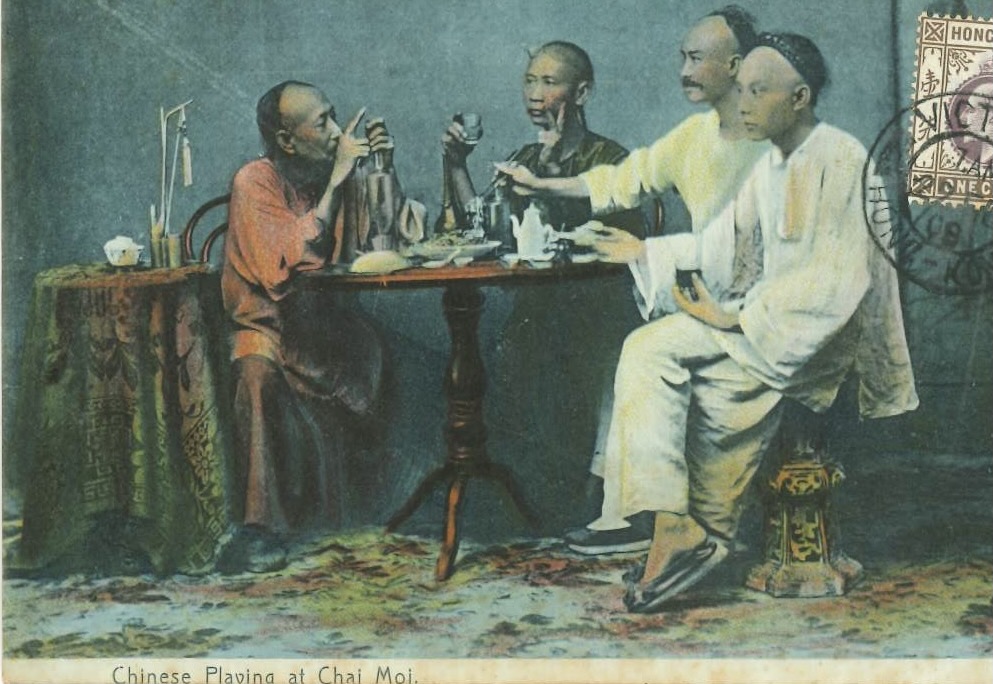

If you lack these prerequisites, why not consider a primitive Chinese finger game called 猜枚. The game is a competition between two players and the rules are as simple as the name indicates: 猜caai1 ‘guess’ and 枚 mui2 ‘piece’ is a measure word used before names of small objects. In Hong Kong, the most common type of caai1 mui2 is the number mui2 十五二十, that is, ‘fifteen, twenty.’ The rules are straightforward. Each player calls out a number from 0 (also announced as 收sau1哂saai3 ‘close all’ in Hong Kong), 5, 10, 15, or 20 (also announced as 開hoi1哂saai3 ‘show all’ in Hong Kong) and simultaneously stretches out fingers of the numbers 0, 5, and 10. If the total of fingers of the two players matches the number called out by the player, then that player wins. The loser is usually penalized by taking a cup of alcoholic beverages.

Without a special tool or skill, this finger-guessing game can be played by people of all ages, any time and anywhere. Besides being simple, a main characteristic of caai1 mui2 is the crying, shouting, and drinking while playing, which is very enticing and amusing. The popularity of the game even attracted the attention of the westerners. In the early days of China-West interaction, Sir George Thomas Staunton (26 May 1781–10 August 1859), 2nd Baronet, accompanied Lord George Macartney to China in 1792. At a young age, Staunton already had a good knowledge of the Chinese language before the Macartney mission. His linguistic expertise in Chinese proved beneficial not only for the diplomatic mission but also for his later employment in the East India Company at Canton (Guangzhou). Reminiscences of Sir Staunton’s connection with Hong Kong can be seen in a few toponyms named after him, for example, Staunton Creek and Staunton Valley in present-day Wong Chuk Hang and Staunton Street (士si6丹daan1頓deon6街gaai1) located in the central business district Central.1

As a China expert, Sir Staunton translated several Chinese texts into English, including Ta Tsing Leu Lee – The Fundamental Laws, and a Selections from the Supplementary Statutes, of the Penal Code of China (大清律例) (1810), which was an essential book for western traders engaging in the China trade. Besides writing about commerce and diplomacy in China, he was also a careful observer, noticing the characteristic lives of ordinary Chinese. One example was the rules and characteristics of caai1 mui2, which he described as follows.2

“The game, called by the Chinese Tsoey-moey, is most usually played during entertainments at which wine is served, the guests severally challenging their neighbours to the contest.—Both parties raise their hand at the same instant, and call out the number of fingers they guess to be jointly held up by themselves and their adversaries; and when any one calls the right number, his adversary drinks off a cup of wine by way of a fine. The fist closed indicates 0, —the thumb alone 1, —the thumb and one finger 2, —and so on. As the action of the hand and utterance of the number, when the game is played fairly, are perfectly simultaneous, there appears no room open for the exercise of skill or judgment—Yet an experienced and quick sighted Chinese will almost always beat an European or a novice at the game; which seems to arise from the latter betraying his intention too soon, through the want of a certain quickness or adroitness in the motion of the hand, which is possessed by the former.”

Though an entertaining game, the noises made by the players and observers could also be a nuisance. That’s why the Hongkong Ordinance, No. 2 of 1872 stipulated that:3

“Every Person shall be liable to a penalty not exceeding Ten Dollars who shall utter Shouts or Cries or make other Noises while playing the Game known as Chai Mui, between the Hours of 11 p.m. and 6 a.m., within any District or Place not permitted by some Regulation of the Governor in Council.”

Though caai1 mui2 is a long-standing and popular drinking game in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, the way it is played has evolved continuously. The penalty is no longer restricted to drinking wine but can take other forms. In addition to the most traditional form of guessing the number, new ways of playing, such as performing specified actions, are created.

Happy Year of the Snake!

1. Wordie, Jason. 2002. Streets: Exploring Hong Kong Isand. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

2. Staunton, Sir George Thomas. 1822. “Notice of a popular game among the Chinese called Tsoey-moey”. Miscellaneous Notices Relating to China, and our Commercial Intercourse with that Country, Including a few Translations from the Chinese Language. (Second edition, enlarged). London: John Murray, Albemarle-Street: Printed by Henry Skelton, West-Street, Havant.

3. Giles, Herbert A. 1878. A Glossary of Reference,on Subjects Connected with the Far East. Hongkong: Messrs. Lane, Crawford & Co.