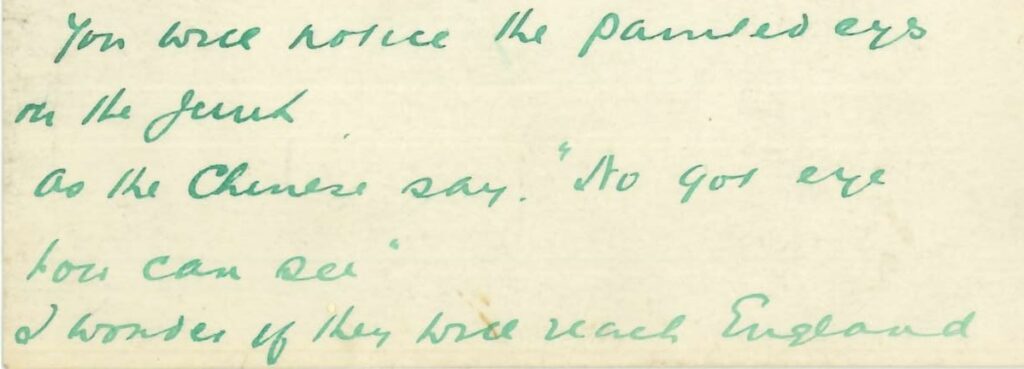

Water covers approximately 70% of the surface of the globe, which means that the lives of a large number of people are in different ways related to the water. Yet, the vastness and depth of the sea are also the source of uncertainties and dangers. As a result, cultures worldwide have rich literature on different nautical lore and beliefs, myths and mysteries, and monsters and superstitions. Seafarers, in particular, adhere to maritime customs about behaviour and language in order not to bring bad luck to their voyages. A long-standing practice in seafaring is painting a pair of eyes on a ship’s bow. Why? As the remark on the featured image says, “No got eye how can see”. The remark, written on the back of a photo of a Chinese junk, shows the belief of the Chinese seafarers that the eyes could symbolically guide them to their destination safely. It is unclear when people began to paint eyes on ships or junks, but this time-honoured tradition is practiced by both eastern and western maritime cultures.

A common belief that different cultures share is that ships, like humans, need eyes to navigate safely in the vast sea, as emphasized by Mahtsze, who worked as a “boy” (house servant) for Albert H. Rasmussen.1

“Most of them were big sea-going craft with huge staring eyes painted in their bows. Mahtsze explained in pidgin-English: “He go long way. Suppose he no have gottee eyes he no can see. Suppose he no can see, he no can savvy what place he belong, what place he go.”

Rasmussen arrived in China in 1905 and stayed there for three decades. He communicated with Mahtsze in Chinese Pidgin English, a language created by the Chinese and the foreigners in Canton (present-day Guangzhou) dating back to the 18th century.

Pidgin English differs from standard English in many ways. For instance, instead of if conditional sentences are introduced by suppose or zero in the pidgin. Question words are more transparently expressed than their English counterparts; typically it takes the form [what + thing to be questioned], for example, what place ‘where’, what time ‘when’, what thing ‘what/which’, what fashion ‘how’. Belong is used in the sense of ‘to be’.

The word savvy ‘to know’ is evidence of European maritime explorations whose outcomes were not limited to economic and political changes but also linguistic interactions. The arrival of Europeans created circumstances in which some forms of contact language were developed in order to allow communication. Contact languages, like pidgins and creoles, resulting from regular cross-cultural contact exhibit linguistic features that could be drawn from the participating language speakers. As in Chinese Pidgin English, the lexicon contains words of English, Chinese, Portuguese, Indian, and Malay origins. A study in The Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Language Structures shows that the word savvy (or other spellings) meaning ‘to know’ is attested in 40 of the 76 contact languages surveyed. Savvy is etymologically related to three Romance languages: saber in Portuguese and Spanish and savoir in French.2 Savvy in Chinese Pidgin English is likely based on saber in Portuguese, as the Portuguese were formally allowed to settle in Macau in 1557.

You may notice that Mahtsze uses the masculine pronoun he to refer to the junk. The number of pronouns in pidgin English is fewer than standard English. Normally, the pidgin only uses the singular pronouns – I, my, me for first-person, you for second-person, and he for third-person regardless of gender and animacy. That’s why he is used instead of she, which is the pronoun used in English. An alternative is to use the word ship or null as in the exchange about chartering ships below.3

thisee piecee ship got insure ‘Is this ship insured?’

what placee come from ‘Where did she come from?’

come Sydney side ‘She came from Sydney’

hap bring passenger? ‘Had she any passenger?’

sixty piecee man five piecee woman ‘60 males and 5 females’

ship makee sailee how muchee day ‘how many days was she at sea’

As the birthplace of Chinese Pidgin English is Canton, the influence of Cantonese grammar on Chinese Pidgin English is not difficult to find. While adding the word side after the place name is superfluous in English, expressions like Sydney side abound in Chinese Pidgin English. Such structure is based in Cantonese in which the locative marker 度dou6 / 道dou6 ‘place, location’ can be attached to different syntactic categories like nouns (悉sik1尼nei4度dou6 ‘in/at Sydney’), demonstratives (呢ni1度dou6 ‘here’; 嗰go2 度dou6 ‘there’), and pronouns (我ngo5度dou6 ‘at my place’). Similarly, the question word what place ‘where’ is based on the Cantonese question word 邊bin1度dou6, ‘what/which place’. While 邊bin1 by itself can be a question word meaning ‘where’; it can also combine with other words to form interrogative expressions like 邊bin1度dou6 ‘where’, 邊bin1個go3 ‘who’, 邊bin1樣joeng6 ‘which one’.4 Therefore, the transparency of question words in Chinese Pidgin English like what place, what thing, and what time parallels how Cantonese constructs such expressions. The sentence ship makee sailee how muchee day illustrates a difference in word order between English and Cantonese. Unlike English where question expressions are fronted to the beginning of the sentence, both Cantonese and Chinese Pidgin English allow question expressions to remain in situ, meaning they stay in the original positions as in declarative sentences. This explains why how muchee day in the pidgin is not fronted like its corresponding expression how many days.

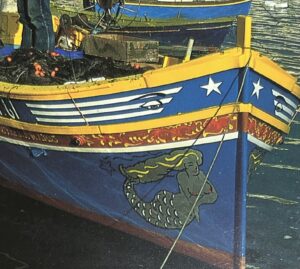

In western culture, it is believed that the eyes would give the ship a fierce look to ward off evil spirits. While working in the Customs in Chinkiang (鎮江 Zhenjiang), Rasmussen remarks on the appearance of the junk,

“By night they looked like huge sea-monsters from another world resting on the swirling waters, their eyes open and watchful. It always gave me a thrill to approach one of them silently at night, clap alongside and jump on board. They were mostly trading junks with their papers in order, and if they did carry a moderate amount of smuggled stuff occasionally I let them keep it. The sailor in me was still very much alive, and I had a sneaking regard for people who had the good sense and decency to give their ships eyes to see with. It was for this reason I often closed my own to many irregularities.”

Compared to junks with no or simple decorations, Fujian traders or 福fuk1船syun4 were very eye-catching. Besides the big round painted eyes, the hull was usually painted red and black, and the stern had elaborate paintings symbolizing auspiciousness. The Chinese junk best known to westerners was ‘Keying’, named after the Manchu statesman 耆kei4英jing1, who represented Qing China in the negotiations with Britain after the two Opium Wars. This 800-ton three-masted junk was bought by some British businessmen in August 1846. Under the command of the British Captain Charles Alfred Kellett, the junk set sail from Hong Kong in December 1846 and rounded the Cape of Good Hope the next year. After a long voyage and diversion to New York and Boston in July 1847, Keying finally reached London in March 1848. Loaded with exotic oriental artifacts and appearance, The junk caused a sensation and attracted numerous visitors, including Queen Victoria and Charles Dickens.5

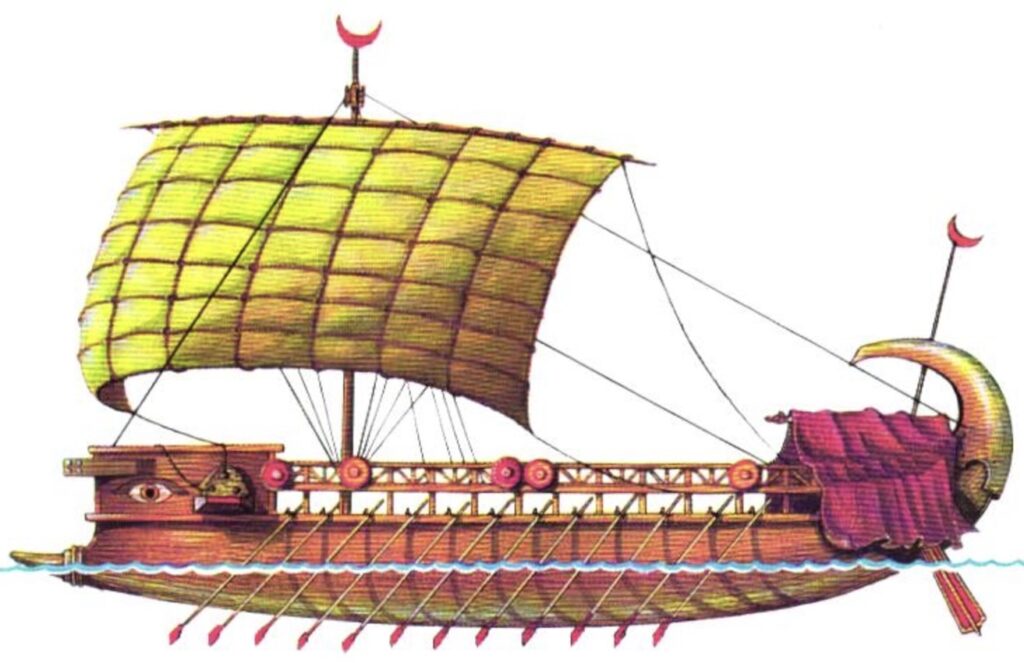

In the west, painted eyes on vessels could be seen as early as on Phoenician ships. The Phoenicians (at its height 1200 BC–300 BC) were well-known for their navigational and trading skills. Moreover, they were innovators in different ways. One way that the Phoenicians impacted the world is language. Unlike the complex cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs that were current writing systems at the time and were only available to the elites, the Phoenicians devised a simplified and easy-to-learn alphabetic script consisting of 22 letters (omitting vowels), written from right to left. Because of the extensive trade networks of the Phoenicians, the alphabet was widespread in the Mediterranean region. It laid the basis for the Greek alphabet (adding vowel sounds) and other western alphabets.

With a coastline of 14,500 km and many inland rivers, sailing vessels were an essential form of transportation in China. Sailing, as a result, has become a part of Chinese culture as seen in the idioms related to nautical practice. Interestingly, a recurrent theme in these idioms is not the eyes but the sails. This is perhaps because sails are an indispensable part of sailing vessels, whereas the eyes are optional. The following are idioms that refer to the sails, namely 帆faan4 or 𢃇lei5, and their word-for-word meanings.

一jat1帆faan4風fung1順seon6

‘one-sail-tailwind’

千cin1帆faan4競ging6 發faat3

‘thosand-sail-to race-to set off’

看hon3風fung1駛sai2 𢃇lei5

‘to watch-wind-to sail-sail’

有jau5風fung1駛sai2盡zeon6 𢃇lei5

‘there is-wind-to sail-full-sail’

The character 帆faan4 ‘a sail’ is used in standard Chinese and Cantonese, but 𢃇lei5 is a unique Cantonese word. It is suggested that since 帆faan4 is pronounced like words such as 煩faan4 meaning ‘troubled’ and 翻faan1 ‘capsize’, so to avoid the inauspicious meaning a coinage 𢃇lei5, which is a near homophone of 利lei6 meaning ‘profit’, replaces 帆.6 To wish people success in whatever thing they do, we say 一帆風順. In its literal sense, 千帆競發 means numerous vessels race to set sail; figuratively, it refers to vigorous and robust development. The last two idioms are often used pejoratively to describe people’s attitudes. Since sailing vessels are propelled by wind power, wind is an important element in sailing as seen in these idioms. If a person 看風駛𢃇, he/she changes course in order to take advantage of a situation. When a person 有風駛盡𢃇, he/she exploits a favourable situation to the fullest extent possible. To advise people not to adopt such an attitude, the prohibitive marker 唔m4好hou2 ‘don’t’ is added, giving 唔好看風駛𢃇 and 有風唔好駛盡𢃇.

Wishing everyone 一帆風順 and 千帆競發 in 2025!

1. Rasmussen, Albert H. 1954. China Trader. London: Constable.

2. Magnus Huber and the APiCS Consortium. 2013. Savvy. In: Michaelis, Susanne Maria & Maurer, Philippe & Haspelmath, Martin & Huber, Magnus (eds.). The Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Language Structures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

https://apics-online.info/parameters/110.chapter.html

3. Tong, Ting-kü. 1862. The Chinese and English Instructor. Canton.

4. 「度 / 道」. 粵典. https://words.hk/zidin/v/108714/%E5%BA%A6

「邊」粵典. https://words.hk/zidin/%E9%82%8A

5. Davis, Stephen. 2014. East Sails West. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

6. 歐陽覺亞, 周無忌, 饒秉才.2018.《廣州俗語詞典》. 商務印書館(香港)有限公司