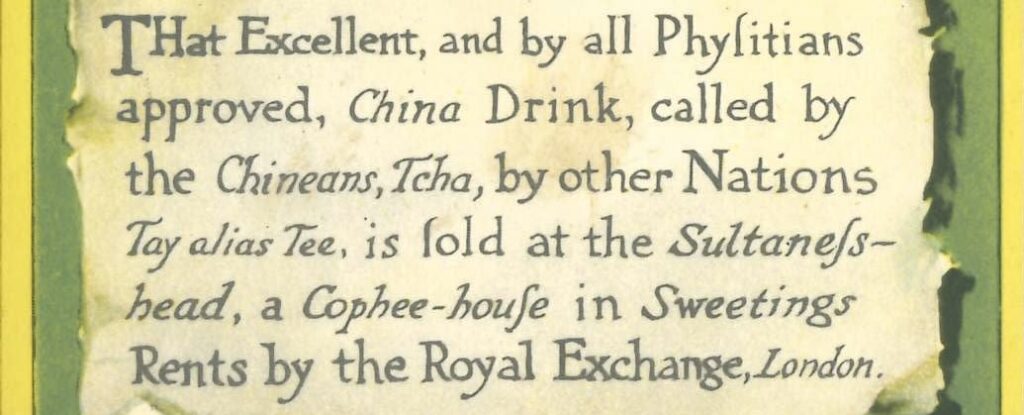

Tea has become one of the popular beverages in Europe since the 17th century. Even coffee houses sold tea from China. The trade card above was produced by the English and Scottish Joint C.W.S. Tea. It showed first newspaper advertisement of tea which appeared in September 1658 in Mercurius Politicus. The advertisement as shown above announced the availability of a “China drink” in a coffee house.

“That Excellent, and by all Physitians approved, China Drink, called by the Chineans, Tcha, by other Nations Tay, alias Tee, is sold at the Sultaness-head, a Cophee-house in Sweetings Rents by the Royal Exchange, London.”

Many languages have a word for ‘tea’. What is interesting is that these words come mainly from two Chinese sources. Östen Dahl collected words for ‘tea’ from 230 languages and discovered that 110 languages use forms derived from Cantonese caa4, 84 languages have forms derived from Min Nan 閩南 (or Southern Min) te, and the rest 36 languages use forms based on other sources.1 The tea bag on the right showed adoption of different Chinese sources in European languages – Portuguese chá was based on Cantonese caa4, whereas Spanish té was derived from Min Nan tê.

The question is: why were these two Chinese varieties chosen? Tea plants grow well in locations such as Guangdong 廣東, where Cantonese is a main language, and Fujian 福建 and Taiwan 台灣, where Min Nam is spoken. World famous teas from China include Keemun 祁門, Oolong 烏龍, Gongou 功夫, etc. Foreign traders borrowed the forms for ‘tea’ from the varieties the Chinese spoke. The Dutch and Spanish were mainly trading with the Min Nan-speaking Chinese, while the Portuguese who were based in Macau traded with the Cantonese.

Europeans’ enthusiasm for tea created a huge market of tea export. Tea became one of the luxurious commodities in the China trade. Tong Ting-kü (aka Tong King-sing) was a merchant and compradore. In his book The Chinese and English Instructor, a dialogue on buying tea was given.2 A buyer was looking for good quality tea and the tea merchant presented several chops (brands) of tea to him.

A: my hear you wantchee buy tea ‘I hear that you want to buy some tea’ 我聞得你要買茶

B: yesee, you hap got ‘Yes, have you any’ 係呀你有麼

A: my got few chop ‘I have a few chops’ 我有幾個字號

B: what kind tea ‘What kind of tea’ 乜野茶呢

A: green tea black tea alla hap got ‘I have both green and black teas’ 綠茶紅茶都有

B: what sort black tea ‘What kind of black tea’ 係乜野紅茶

A: fine Congo 嫩裝工夫茶

Hap got was derived from have got and indicated possession. Congo 工夫茶 (also Congou) is a kind of black Chinese tea produced in the Fujian province. Note the difference in how the West and Chinese call the more oxidized tea – the West call it black tea because of the color of the tea leaves, while the Chinese call it 紅茶 (literally ‘red tea’) because of the color of the brewed beverage.

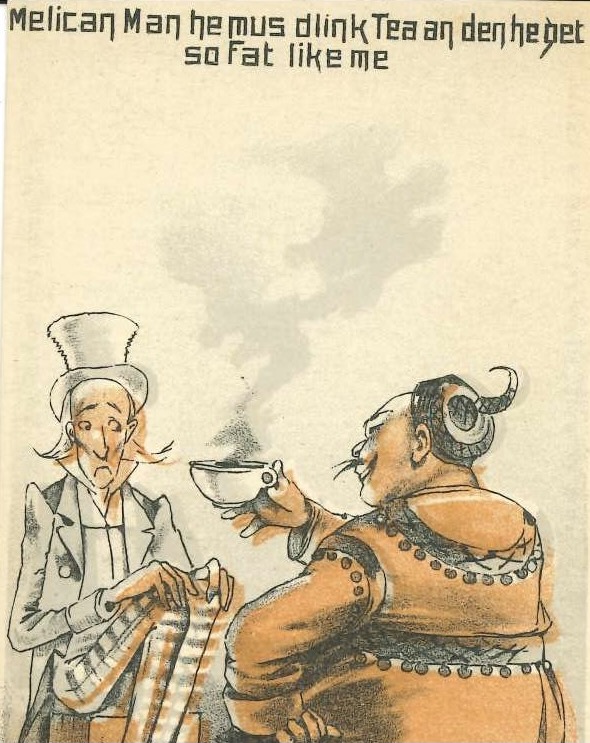

Trade in tea was also a lucrative business in America. In American history, a major event related to tea was the Boston Tea Party (1773). As British was heavily in debt, the British government imposed different taxes such as the Tea Act (1773) on American colonists to gain revenue. The Americans were enraged because the Act allowed the British East India Company to enjoy duty-free when selling tea to the colonies. This made American traders less competitive than the British and provoked the colonists to throw all the chests of tea imported by the East India Company into the harbor. This important event was known as the Boston Tea Party.

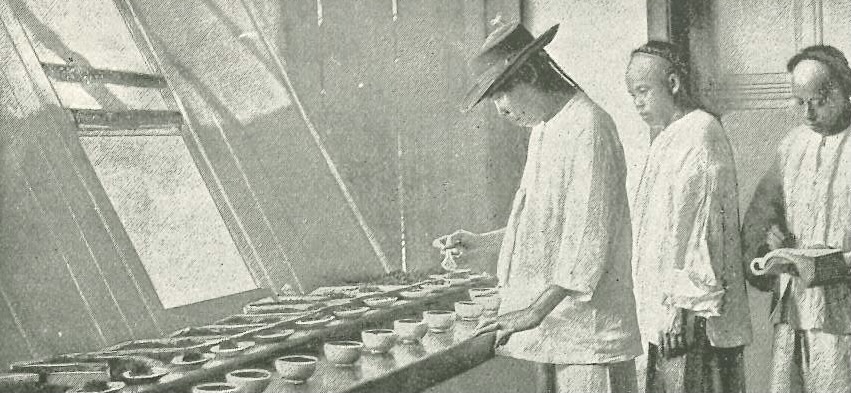

All foreign traders wanted to sell their teas at good prices. Therefore tea experts were required to test the qualities of teas. Such expert was called chaa-sze (茶師 ‘tea expert’), whom the missionary Robert Morrison defined as “a person who inspects the quality of teas and decides the prices, ie, at Canton so called; a Tea Inspector.”3 So, how did a cha-szetest teas? Giles (1886) gave us s brief answer – “A tea-taster; or more irreverently, a tea-gobber, from the habit of spitting out the tea tasted, instead of swallowing it.”4 Becoming a cha-szerequired extensive knowledge in teas and sensitive taste buds. The office of the cha-sze was also very thoughtfully situated and designed. John Thomson, a photographer, described a tea-tasting room at Canton as follows:5

“The windows of the room have a northern aspect, and are screened off, so as to admit only a steady sky-light, which falls directly on the tea-board beneath. Upon this board the samples are spread in square wooden trays and it is under the uniform light above described that the minute inspection of colour, make, and external appearance of the leaves take place. On the shelves around the room stand rows of tin boxes, identical in size and shape, containing registered samples of the teas of former years. These are used for reference. Even the cups, uniform in pattern, and regularly ranged in rows along the numerous tables required, have been manufactured especially for the business of tasting tea. The samples are placed in these cups, and hot water of a given temperature is then poured upon them. The time the tea rests in the cups is measured by a sand-glass, and when this is accomplished all is ready for the tasting. All these tests are made by assistants who have gone through a special course of training, which fits them for the mysteries of their art. The knowledge which these experts thus acquired is of great importance to the merchants, as the profitable outcome of the crops selected for the home market depends, to a great extent, on the judgment and ability of the taster.”

1. Dahl, Östen. 2013. Tea. In Matthew Dryer and Martin Haspelmath. (eds.). WALS Online (v2020.3) http://wals.info/chapter/138

2. Tong, Ting-kü. 1862. The Chinese and English Instructor. Canton.

3. Morrison, Robert. 1819. A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, in Three Parts. Part II. Macao: The Honorable East India Company’s Press.

4. Giles, Herbert A. 1886. A Glossary of Reference on Subjects Connected with the Far East. (second edition). Hongkong: Messrs. Lane Crawford & Co.

5. Thomson, John. 1873. Illustrations of China and its People. Vol. 1. London: Sampson Low, Marston Low and Searle.